By BRRN Radical Ecology Committee

Coastal Louisiana is home to 41% of the United States coastal wetlands and is the world’s seventh largest delta ecosystem. The region is covered with natural levees, barrier islands, forested wetlands, and marshes formed by Mississippi River deposits. Historically the state’s wetlands provided protective barriers for diverse coastal communities against hurricanes and extreme storms, while also serving as important ecological deterrents to climate breakdown through carbon sequestration. Currently, Louisiana has one of the fastest rates of coastal land loss and relative sea-level rise on the planet, twice the global rate. [1] This sustained destruction of coastal Louisiana began with the colonization process- separating water from arable land- and it is bound up with the accumulated, appropriation of land, energy, and unpaid labor by fossil-fuel industries. Capitalism is exhausting the carrying capacity of this wetlands region due to its role as an extraction zone. Cumulative development is degrading the ecosystem itself and its ability to protect from accelerating climate disasters. We must determine an effective means to protect this region, both to regenerate the coast and protect the communities that call it home.

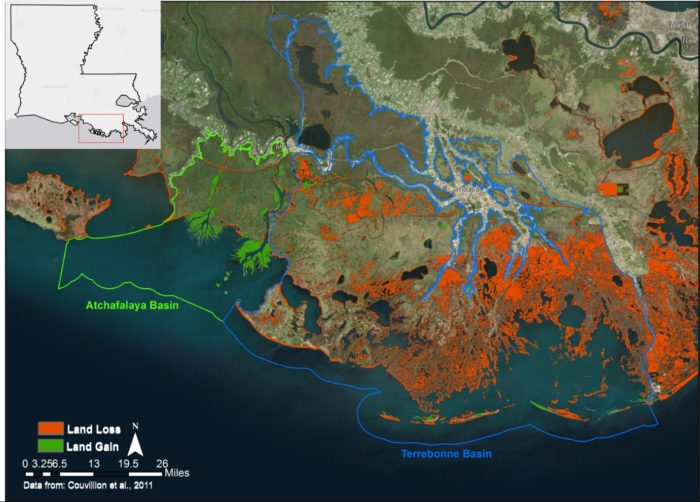

90% of the coastal Louisiana wetlands are considered to be “under threat” given the direction of development within the state of Louisiana. Measuring that in terms of land loss, 70% stems from the effects of industrial growth. Oil and gas industrial production leads to the construction of dikes, levees, and damming of the Mississippi river for extraction and shipping, Other sectors supported by these expansions include both industrial agriculture and logging. The extensive man-made system prevents sediment and silt from reaching the Delta, obstructing the land from building itself up and replenishing the ecosystem cycles.This deteriorating land is caused primarily by erosion, by submergence in which wetlands sink and the sea levels rise, and by the direct removal of land. Direct removal of land occurs through a combination of dredged canals for navigation and pipeline construction, oil drilling, deforestation, agricultural drainage, and hurricanes. Organic sediments which would are deposited by the river system and consolidated in the Delta to form new land is interrupted by subsidence, as the land gradually caves in and sinks. The rates of land loss are significantly higher near oil and gas production fields. [2]

Aside from losing land within these regions additional problems come from the disequilibrium between salt and fresh waters ecosystems. Dredging pathways through marshland has continued since the first coastal zone oil lease in 1921, enabling saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico to rush in during storms and high tides. [3] The bayou forest ecosystem collapses as the land becomes filled with saltwater as well as other toxins, such as fertilizer runoff from industrial agriculture. The ecological effects are compounded by imminent submergence and further land loss. [4] Metabolic exhaustion plays itself out as Capital, Power, and Nature are reconfigured throughout the region as this frontier zone of appropriation diminishes.

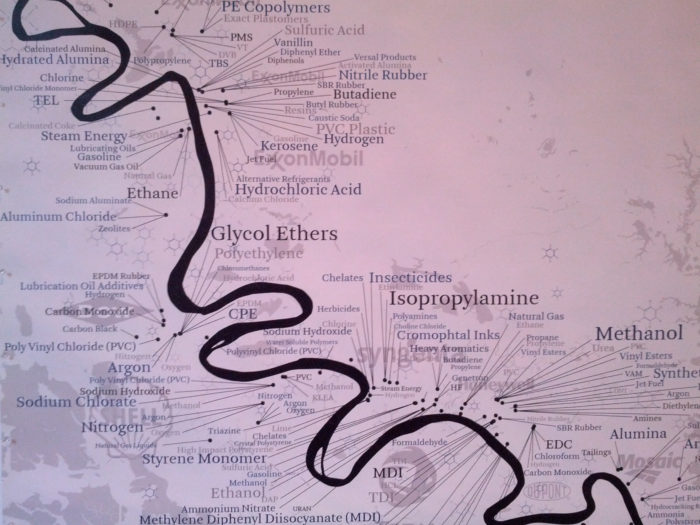

The Louisiana Gulf region, like other resource zones of un-commodified work and energy, has over time transposed its slave-based plantations of cotton and sugar into an increasingly toxic geography of extraction. Both its Black and Indigenous populations have been disproportionately dispossessed of land and resources through the continual expansion of petrochemical production. This region has become a primary extractive zone for capitalist investment and accumulation. Other economic sectors that could otherwise thrive in the region are sacrificed to support a bioregional transformation of cheapening for the benefit of the energy and petrochemica industry. The Mississippi, like many other global deltas, has become a “tap” for petroleum companies: they exist as extraction provinces. Echoing the words of the oil industry::

Deltas serve as point sources … The delta form(s) a geomorphic bulge which projects seaward and allows land and shallow offshore drilling rigs to reach deep targets which could only be reached by more expensive rigs in deeper water areas adjacent to the delta. Significant hydrocarbons have been discovered in at least eighteen deltaic provinces worldwide. [In other words, deltas provide easy access to energy sources, where waste can be easily discharged, cheaper to drill and extract, as well as being very lucrative-BRRN REC]. [5]

As the petrochemical corridor of the Louisiana Gulf taps more wealth from the region as an ‘energy sacrifice zone,’ the unpaid costs of waste production and land loss outstrip both the abundance of “resources” available as well as the value that can be extracted. The cumulative appropriation of new streams of unpaid work/energy leads to a disproportionate volume of waste over time. Spills and emissions seep into the land, water, and air from the refineries, chemical industries, and hazardous waste sites along the Mississippi river. The deltas become clogged and overflowing ‘sinks’ for industrial waste. These ecological ‘sinks’ are increasingly vulnerable to extreme storms, land submergence, and rising sea levels. Value and waste are internally bound, so that over time Capital loses the ability to extract surplus value from the region. [6]

Racialized Extraction Zone

This bioregional crisis in the Gulf Coast of Louisiana has been a cumulative process built on racialized and colonial capitalism. Genocide, dispossession, and displacement of indigenous communities; and a denial of their legitimate right to exist continues to mark the landscape. In the 1800s, many Indigenous communities fled colonization into previously uninhabited southern ends of Louisiana’s coastal bayous. [7] Some of these communities still live along these coasts in barrier islands and tidal estuaries, subsisting on fishing, shrimping, and small gardening. Since the early 20th century, they have co-inhabited extraction zones with offshore oil-drilling operations, pipeline infrastructures, and other petrochemical facilities. The loss of landmass- including many barrier islands to the south of these tribal communities- has decreased their natural protection from the Gulf waters, exposing them to intensified hurricanes and tropical storms. [8] This is a perpetual “shock zone” of disasters, facing cycles of climate-induced displacement with each new storm. Much of the biodiversity of these bayous faces destruction, killing medicinal and edible plants, trees, and driving out many of the animals that these communities depend on for refuge and food. [9]

From the forced relocation of tribal ancestors, through the land grabbing by real estate developers and petroleum corporations, to the state’s flood-protection plans that discount and pollute tribal lands, this colonial legacy of Capital appropriation continues to devastate and traumatize. These accruing disasters are a part of a “legacy of atrocities” that these tribal communities experience as a continuation of policies favoring interests of capitalism and the state. [10] For instance, the BP Deepwater Horizon Disaster reverberates through the region’s waters and aquatic ecosystems. Immediately following the Deepwater Horizon explosion, British Petroleum applied 1.84 million gallons of dispersants, mainly Corexit chemicals, that allowed the spilled oil to mix with the water. [11] The region’s fish have been documented with serious lesions and shrimp have become deformed due to their exposure to high levels of compounds- such as benzene-released from dispersed crude oil. [12] This is not an isolated incident, however. Major deep offshore oil disasters- such as the continuing Taylor Energy oil platform spill- also seriously affect the landscape. Since 2004 the broken Taylor platform has leaked 10,500 to 29,000 gallons of oil per day, making it one of the largest and longest-running spills in North America. [13]

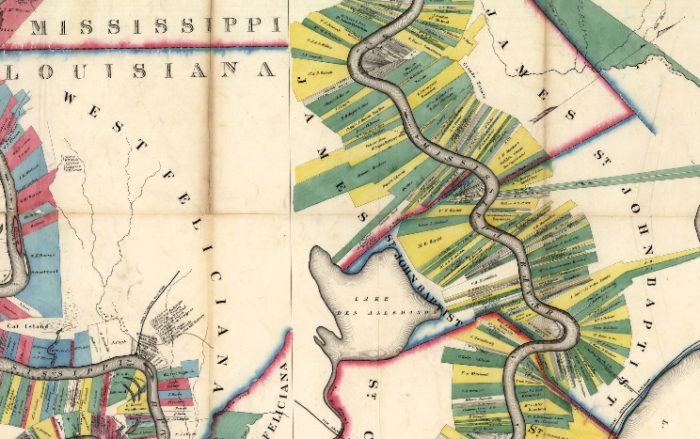

Louisiana’s African-descendent communities share a related history of appropriation and exploitation. The “River Region” between New Orleans and Baton Rouge was once the heart of the South’s slave economy, with nearly 300 sugar and cotton plantations along the lower Mississippi. [14] Its colonized geography of agricultural enclosures and unpaid labor created what Frantz Fanon called “a world divided into compartments” or “a world cut in two.”[15] Both African and Indigenous communities experienced forced displacement and enslavement during colonialism. Due to the shared experiences, Black runaways frequently joined indigenous tribes to escape plantations leading to African-Indigenous alliances during slave revolts and insurrections against white rule. [16] The dominant paradigm of the time established white supremacy as the base logic of the entire regional economy. As with other colonial ventures, unpaid human labor and unpaid energy of ecosystems are harnessed for Capital accumulation in the region.

The logic of “cheap nature” degrades the work and lives of the colonized not only along racial lines but also by devaluing their labor and deteriorating the conditions in which they live. Through these systems, the capitalist world-ecology profits from “cheapening,” reproducing forms of domination, appropriation, and exploitation throughout the social order. The Capitalocene organizes relations between humans and the rest of nature through binary “world cut in two” logic. What is most valued in “commodified profit” and “tapped resources” is also what is deemed white and male. What is not valued, the uncommodified work/energy of “women, nature, and colonies” is left from the paid ledgers of Capital. [17] These “free gifts of nature” are to be used and disposed of in the production process as “externalities” and waste, respectively. The surplus of what is unpaid is violently maintained through the expansion of frontiers as demonstrated through settler-colonial power. [18] Violent appropriation is maintained through the incestuous relationship between Capital and the State, which allows for the continued exploitation of labor in producing petro-commodities for global markets. Frontier conquest of extraction zones ensures both the continual appropriation of unpaid labor/energy and the exploitation of paid labor in commodity production. Together, they co-produce greater capital accumulation of value.

This cycle of appropriation is evident in the construction of the Mississippi levee system. Separating the land from water through flood control measures allowed for greater privatization by white landowners and business owners. While the jetties, dams, and other navigation structures opened New Orleans to greater markets for its cotton and other commodities; the levee system helped reinforce racial segregation. Many former African slaves- who lived on the edges of the plantations in woods and wetlands- faced displacement by the levees. The constructed levees destroyed these edges, enlarging the cotton plantations and forcing black folks back into plantation labor. [19] Legislation maintained that the levees were to be built “by hired labor or otherwise,” resulting in local authorities and landowners using prison labor, homeless vagrants, and coerced plantation laborers. Most of these laborers were Black men, while White men owned most of the acreage protected by the levees. Once the levee system was proven to be a boon for Capital in the Mississippi Valley, the same model was used to “improve” rivers and appropriate indigenous land in the West. This continued colonization allowed for production of cheap grain which would find their way to the Port of New Orleans, to be sold on global markets. [20]

With the advent of fossil fuels, former plantations were sold to emergent oil companies, eager to obtain cheap Mississippi riverside territory, rich in untapped “resources.” The labor pool was inexpensive and expendable and proximity to a major seaport ensured a global market for the extracted value. As this petrochemical corridor expanded its frontier along the Louisiana Coast and offshore, the pollution and environmental degradation affected those closest to its factories and refineries: disproportionately the descendents of African slaves and Indigenous communities. For many African-descendent communities, the transfer from Plantation to Chemical Plant was effectively “exchanging one plantation master for another.” [21]

The primarily African-American community of St. Gabriel, Louisiana witnessed a striking example of this environmental racism. In 1987, 15 cancer victims identified to live within a 2 block radius, setting off a tidal wave of diagnoses along what would become known as “Cancer Alley.” This eighty-five mile of the Mississippi coast stretches between Baton Rouge and New Orleans and it is packed with approximately 150 petroleum refining or chemical factories. The amount of toxic and hazardous wastes regularly released overwhelms the landscape. Cancer Alley comprises the parishes (counties) of St. James, Ascension, East Baton Rouge, West Baton Rouge, Iberville, St. John the Baptist, St. Charles, Jefferson, Orleans, Plaquemines, and Assumption. A disproportionately number of Black communities live in close proximity to the petrochemical facilities. [22] As of 2018, Louisiana has the fifth-highest cancer death rate in the U.S. and numerous studies show the rates are inordinately higher among the state’s non-white population. [23] Most of the 11 parishes of Cancer Alley do not meet EPA standards for safe levels of ozone and these same parishes account for 63.5% of the state’s on- and off-site release and disposal of toxic and/or hazardous compounds. Petrochemical plants, many which produce polyvinyl chloride (PVC) products, continue to deteriorate the public health conditions of these African-American communities. In the mostly low-income, working-class Black small towns of Cancer Alley, industrial accidents and accidental releases are prevalent and consistently observed over time. [24]

As extraction frontiers begin to diminish in the Gulf region, the technologies used to appropriate this unpaid wealth become more complex and hazardous. Contrast a 1930’s cricket oil pump to the massive offshore drilling platforms that currently line the Louisiana coast. [25] As Capital costs increase with the use of advanced extraction technologies, the financialization of these ventures is bringing less accumulation of surplus value. This negative value is evidenced industry-wide in cost-intensive and volatile processes such as hydraulic fracking and bitumen conversion of tar sands. The cumulative toxicity from natural gas extraction and and the petrochemical industries cause a host of public health issues as these intensive methods expand: developmental, respiratory, digestive, neurological, renal, and dermatological conditions are all documented. Long-term monitoring of air quality and charting of spills and gas releases show a substantial increase throughout the region. Each offshore oil platform generates over 214,000 pounds of air pollutants each year. The oil industry is discharging not only hazardous organic compounds, but radioactive as well. Drilling wastewater is released into the Mississippi or on the Gulf coast with high Radium-226 concentrations. This effluent is known to have appreciable concentrations of this and other radioactive isotopes substantially higher than safe drinking levels. [26] Yet the petrochemical companies are not content with the current decay: as wetlands sink into the Gulf waters, this submerged land is privatized to allow additional offshore drilling platforms and pipeline infrastructure

The toxicity of this petrochemical extraction zone strains frontline coastal communities in their attempt to maintain necessary levels of social reproduction. Their racialized status limits employment to low-paying service, small agriculture, and fishing jobs; adjacent to petrochemical complexes. Subsistence gardening and fishing remain a substantial part of livelihoods and community resilience in the face of climate breakdown. The oil, gas, and supporting industries, do hire some Black, Indigenous, and migrant workers, but typically in lower-paying oil rig, tugboat, or welding jobs.This work is often precarious and seasonal with poor job-safety oversight. [27] Capital’s success depends on these under-reproduction strategies, reinforced through racial and ecological appropriation. The socially necessary levels of reproduction these communities need go unpaid. Most industry jobs go to white communities around the petrochemical plants or to white commuters who live substantially farther from the facilities. [28]

The “cut in two” logic of racialized capitalism functions through divide and rule, pitting one section of workers against another, often along racial and colonial lines. While the capitalism creates economic competition between workers for jobs, the ruling class uses racist ideology to divide workers against each other, which is reinforced throughout the social order. This is evidenced by large sections of “white” workers and communities throughout Louisiana, who face both heavy labor exploitation and environmental degradation from extraction, but still maintain support for these fossil fuel industries. Many are culturally and politically conservative, accepting both governmental and industry narratives that seek to omit and erase real injustices, and so deny their own and others exploitation and oppression. Systemic racism plays a large part in reinforcing these labor divisions through antagonism and denial. Material conditions confirm that when one group of workers suffer oppression, it negatively impacts the entire working class. Winning over “white” workers to ecological struggles against Capital is essential to recomposing the broader working class.

Racial segregation is reinforced by continued dispossession from vanishing or appropriated coastal land. Displacement, fragmentation, and relocations are common as these communities fight to survive ecological collapse. Climate migration increases as a flight away from the extraction zone. Regional ecological and economic exhaustion continue to produce cumulative reproductive crises, as well as crises of rising wastes and diminishing profits.

L’Eau Est La Vie (“Water is Life”)

As coastal frontline communities attempt to survive and adapt in an “energy sacrifice zone,” a culture of resistance, nurtured in the histories of abolitionist and decolonial struggles, is emerging. This is a direct challenge to the petrochemical frontier strategy of Capital and the State. The growing movement draws inspiration from the indigenous water-protectors at Standing Rock and previous environmental justice struggles of Cancer Alley towns such as Diamond, Wallace, and Convent. This resistance is formed by a diverse convergence of environmental organizers from various Indigenous, Black, and other working-class communities; building a counterpower movement across Louisiana to prevent the proposed Bayou Bridge Pipeline. The 162 mile pipeline is designed to bring fracked crude oil from the North Dakota shale fields across coastal Louisiana. The route passes through the eastern Atchafalaya Basin forested wetlands destroying more than 940 acres, the largest continuous wetlands in the U.S. It would continue across coastal Louisiana, impacting more than 450 additional acres during construction. [29]

The Atchafalaya Basin is a particularly important ecosystem in the US, its 885,000 acres make it the largest river swamp and continuous bottomland hardwood forest in North America. (Etymologically, Atchafalaya is derived from the Choctaw words for “long river,” hachcha and falaya). It contains the most productive wetlands on earth. The proposed Bayou Bridge Pipeline will extend damage beyond previous oil and gas projects. Observed damages from those ventures include spoil banks, altered water flow, and disrupted sedimentation patterns in their routes. Making such changes to the landscape impairs water quality, destroys wildlife habitats, and disrupts fishing communities. The imminent threat of spills, leaks, and malfunctions endanger the Bayou Lafourche which is the drinking water source for some 300,000 people including the United Houma Nation and the residents of Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, and Lafourche Parishes. Ecologists predict that compromising the integrity of Bayou Lafourche will cause further erosion and subsidence, leading to freshwater and land loss throughout the region. Plans are to make the Bayou Bridge Pipeline (BBP) terminate in the predominantly African-American riverport town of St. James. The town is already a network of petrochemical storage tanks and facilities vulnerable to public health disasters. Unfortunately, there is no emergency exit plan for its mostly elderly residents in case of a catastrophic failure of these systems. [30]

Since early 2017 this pipeline resistance movement has centered its activity in Rayne, Louisiana, out of L’Eau Est La Vie (“Water is Life”) Camp. From the camp,residents surveil, organize, and employ collective direct action along the proposed pipeline route. The Bayou Bridge resistance can be considered- and is seen as such by many camp organizers- as a direct continuation of the Indigenous struggle at Standing Rock, as the Bayou Bridge Pipeline connects to the tail end of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Both of these decolonial struggles are at the nexus of ecology, indigenous, feminist, and Black liberation resistance to Capital extraction. They struggle against the racist and patriarchal systems to protect the stolen Chata Houma Chittimacha Atakapaw Indigenous territory. L’Eau Est La Vie water-protectors seek to disrupt and stop construction in the Atchafalaya Basin. The water-protectors have engaged in collective direct actions including tree-sits, blockading construction sites (with kayaks), and locking down to construction equipment. Like Standing Rock- which brought together diverse First Nations communities and non-Indigenous participants- the water-protectors at L’Eau Est La Vie Camp are equally diverse with Choctaw-Houma, Chumash, Apache-Cheyenne, Lakota, Creole, African, and Cajun, and other working-class participants. [31]

A number of the core organizers within the L’Eau Est La Vie camp are indigenous women and women of color. They play key roles in the L’Eau Est La Vie Camp, not only in the direct actions, but also through providing education, healthcare,and food. This collective organizing may be seen as an integrative expansion of necessary social-reproductive labor. In this context, social reproduction becomes transformed as a primary site of struggle: a site of violent capitalist accumulation pitted against persistent decolonizing resistance. [32] Social-reproductive labor also expands towards community and kin networks into relations of care for the land, the water, and other non-human natures. These water-protectors are transforming their social reproductive labor within a site of creative resistance to both white settler patriarchy and Capital. Their brilliance is demonstrated in strategic divestment campaigns, legal defense, and extensive solidarity-based organizing throughout the coastal communities. All of this to stop the BBP from going into operation.

These water-protectors are also challenging eminent domain. The state and/or corporate entities reserve the right to seize lands and resources, based on purported “public benefit.” The settler-colonial state works with petrochemical companies to apply his legal precedent, confiscating ‘cleared’ land for private development, and appropriating Indigenous land and resources. One example is the Flood Control Act of 1928, Under this legislation the federal government assumes the authority to take possession of any lands needed for easements, right of way, etc.; to protect “private property and national interests.” [33] The decolonial challenge to eminent domain contests this unjust industry appropriation while seeking justice for past colonial land theft. In December 2017, water protectors bought land in the name of Louisiana Rise, a group organizing a just, renewable energy transition in South Louisiana. The organization then publicly granted and returned the land to the Atakapa-Ishak Nation. L’Eau Est La Vie now uses this land as a center of resistance in the path of the proposed pipeline. [34]

The purveyors of the pipeline- Energy Transfer Partners (ETP)- recently escalated its tactics to intimidate those at L’Eau Est La Vie Camp. The corporation persecutes water protectors through “felony trespass” arrests, made possible through Louisiana’s new “critical infrastructure” law. This state legislation basically turns the existing law on trespassing into a felony when it occurs near “critical infrastructure” or construction sites for critical infrastructure, which includes oil and gas pipelines. It also involves “conspiracy” charges to enter or damage these sites with penalties both in prison times up to 10 years in prison and up to $10K in fines. This partnership between ETP and Louisiana effectively criminalizes oil and gas pipeline protests to maintain dominance in the region. Despite this repression the water protectors continue to expand their resistance. [35] In July-August 2018 the water-protectors set up a second campsite with permission of affected landowners. A dozen organizers were arrested under “felony trespass” charges. The struggle is currently in a legal standoff with BBP representatives who filed to expropriate the land in the “public interest.” The landowners’ countersuit alleges the pipeline offers no public benefit and in fact goes against public interests. [36] The countersuit cites ETP’- and its affiliates’- extensive spill and leak record, including 527 incidents from 2002 to the end of 2017. These industrial accidents collectively resulted in the release of 3.6 million gallons of hazardous liquids into the environment. [37]

A countersuit offered by the water protectors- in partnership with local landowners- maintains that pipelines have significantly contribute to Louisiana’s rapid coastal erosion crisis and reliance on fossil fuels, exacerbating climate breakdown. [38] On December 6, 2018, the Louisiana judge presiding over the case ruled that ETP does, in fact, have the right to seize the property following Louisiana state legal precedent. His ruling acknowledged the illegal behavior of ETP, yet still ruled in its favor, reinforcing Louisiana’s consistent history of collusion with the petroleum industry. The state’s actions allow the private interests of oil companies to trump those of its population. The state uses its power of expropriation—i.e., eminent domain,a “right” usually reserved for governments to construct highways or other public works- to support capital accumulation. Nearly 86% of the BBP has been constructed, and Capital in Louisiana hopes that the last 14% are completed with full support of the state. A countersuit intends to appeal the ruling to stop the pipeline from going into commission and forcing ETP to dig up the existing buried pipe. [39]

Regardless of the final outcome of BBP, the decolonial struggle against Capital appropriation has built counterpower alliances between community residents and ecological organizers. Indigenous, Creole, Black, and other non-Indigenous communities are uniting across Louisiana for a shared future. From the Cajun Atchafalaya crawfishers and the United Houma Nation to the black community in St. James, the struggle against the Bayou Bridge Pipeline has mobilized grassroots, sustainable networks for counterpower. The resistance occurs at the intersections of anti-racism, Indigenous autonomy, decolonial feminisms, and climate justice. Given the 20 plus pipelines that are proposed to cross Indigenous territories and communities throughout the U.S. and Canada, the building and sustaining of decolonial movements is paramount. As Capital’s frontiers are diminishing, the lessons learned through these struggles—both the losses and the gains—become imperative.

Bioregeneration against Climate Breakdown

There are increasing systemic contradictions within Capital that present opportunities for broader class struggle. As the appropriation frontiers of fossil Capital decline, they become more vulnerable to collective resistance, especially self-determined approaches. Diminishing returns on financial investment due to rising technical and production costs, the over-accumulation of capital, and the ongoing and impending biological shifts from climate breakdown suggest that substantial cracks are forming in the Capitalocene “cheap” natures strategy. [40] What needs to be addressed in our strategy is how to use these faults to begin building alternatives to Capital’s model and effectively resist.

Ecological restoration and climate change mitigation entail a qualitatively different approach than what is offered by states and capitalist industries. In Louisiana, building new land banks, rerouting levees, or constructing other “walled” barriers to prevent land loss or protect communities from climate storms and hurricanes from the Gulf will not resolve these exacerbating conditions from climate breakdown. BP’s feeble attempts to “clean up” the Deepwater Horizon Spill through “tech-friendly” approaches like spraying toxic Corexit dispersants were as successful as the unsubstantial monetary payouts to those affected, if found “eligible” for damage compensations.

The Louisiana Coastal Preservation and Restoration Authority’s (CPRA) Coastal Master Plan proposes dredging and river diversions to build up coastal edges in open water areas to reduce flood risk and slow land loss. The suggested solutions do not begin to address the ecological factors causing rapid land loss or flooding. Solutions being absent from the plan should come at no real surprise, however. The major planning for CRPA development came from the oil and gas, commercial seafood, and navigation industries (although CPRA initiated and “consulted” community and small landowning focus groups for involvement in the continued evolution of the Plan). [41] Given the class and racial composition of these groups- expectedly skewed toward the dominant social classes-, the cards are stacked against the racialized coastal communities and the powers that be will determine the Plan in the end. The domination is codified in the plan as it stands. The 50-Year Master Plan for a Sustainable Coast has a red line indicating where hurricane protection systems will be placed. Land north of the red line will be protected from flooding and land loss by state-sponsored restoration and protection, while that south of the line will not. The southern boundary excludes many of the Indigenous tribes and black communities. [42] This refusal to protect mirrors racial “redlining” in real estate zoning, with the implicit goal of allowing petrochemical companies to acquire coastal property after catastrophe. The state has legal authority to designate the outlying land as Locally Unwanted Land Use (LULU) zones on behalf of the petrochemical industry, leading to eventual appropriation. The State and Capital are unable to “fix” or effectively mitigate Louisiana’s bioregional crisis of land loss, ecological toxicity, and climate breakdown; so they instead intend to capitalize to the very limits of the region.

More grassroots, community-based solutions for coastal restoration are necessary. These approaches require a qualitative ‘shift’ away from a capitalist world-ecology towards a reparations ecology. The move towards a reparations ecology involves a fundamental transformation in social relations. Movements must acknowledge and remember the violence and inequality which capitalism applies to organize life between humans as well as humans and rest of nature. [43] Reparations ecology recognizes the debt owed is “wealth extracted from our communities through environmental racism, slavery, food apartheid, housing discrimination, and racialized capitalism.” [44] It also strengthens emancipation through building and uniting decolonial, ecological, and abolitionist struggles. We begin to repair and recreate relations that nourish justice and sustainability in reciprocal and care-oriented ways, recognizing that nature can no longer be an expendable resource, used to benefit the very few at the expense of degrading the rest of life. This care-oriented ethos does not make these demands on redistribution grounds, but questions the very basis of capitalism. Reparations ecology advances more substantial demands that seek to de-commodify life. This self-organizing process involves communities restructuring and restoring food, land, housing, healthcare, education, etc., along communal, social-reproductive lines. [45]

The seeds of reparations ecology are seen in climate-disaster communities already just like those in Louisiana. People continue to demonstrate through self-managed direct action, mutual aid, and solidarity, that communities affected by climate catastrophes can rebuild. By “making do with what is at hand” they can efficiently meet human needs even under the most adverse conditions. Disaster communities can organize through mutual aid towards the commoning of resources based on specific collective needs. It is essential to emphasize within these struggles that situations are reconfigurable and that solutions can be found through self-organization. In this way the goal becomes how to best “pull [capitalism] apart and repurpose its components to new ends: an ecological satisfaction of human needs and not the endless valorisation of capital.” [46] Through building and integrating sustainable “infrastructures of resistance”into a comprehensive approach, communities can respond more effectively to climate disasters and begin to restructure communities towards more long-term solutions.

Bioregeneration is an integral component in this reparational shift. As these coastal wetlands have become degraded and their drainage systems destroyed, significant amounts of carbon are released into the atmosphere in the form of methane and other greenhouse gases, reducing their ability to sequester additional carbon. Unlike Carbon Dioxide Removal and other “tech-oriented” approaches to climate breakdown, bioregeneration creates a sustainable biodiversity gain for both human and non-human communities. Especially in relation to carbon sequestration systems, bioregeneration of wetlands will allow storage of excess carbon, via photosynthesis, to help mitigate accelerating climate breakdown. Carbon is stored in wetland vegetation such as mangroves, salt marsh grasses, and seagrasses. These terrestrial wetland soils function as carbon sinks through organic sedimentation of eroded soil, leaves, and tree debris that is deposited into low-lying wetland areas through decomposition, creating new land and protecting these communities and habitats from Gulf disasters and submergence. [47]

The struggles to stop the BBP and mitigate Louisiana’s bioregional crisis involve significant changes to the landscape through bioregeneration. The coastal region needs largely unrestricted water flow and sedimentation processes to continue in the Atchafalaya and Mississippi Rivers for effective restoration to occur. An example of this process is seen in the Atchafalaya Basin. In 1942, the Army Corps of Engineers dredged a channel from the Atchafalaya River to the Gulf of Mexico, splitting the flow of water and sediment between the Atchafalaya River and this newly created Wax Lake Outlet. Over time, sediment filled Wax Lake, creating both the Wax Lake Delta as well as a secondary delta built by the Atchafalaya River. Between 1932 and 2016, while every other basin was losing land, Atchafalaya gained six square miles (4,000 acres) of wetlands. The Atchafalaya River receives 30 percent of the combined flow of the Mississippi and Red River along with a constant stream of sediment that then deposits. The Atchafalaya Basin continues to experience net land gain through re-sedimentation, the new land pushing out into the Gulf. The Atchafalaya ecosystems are regenerating, despite the challenges affecting other areas of the Louisiana coast. [48]

The Terrebonne Basin is located on the eastern coast of Louisiana. In contrast to Atchafalaya, the Terrebonne has lost 550 square miles (30,000 acres) of wetlands since the 1930’s. The Basin is marked by widespread infrastructure intrusions like dams, channels, and dredging. Due to these, the Terrebonne Basin receives limited amounts of freshwater from the Atchafalaya River, keeping it sediment and freshwater poor. While the exhausted Terrebonne wetlands continue to disintegrate, coastal communities become increasingly vulnerable to displacement and disaster. [49] It is possible to reverse this tide, to make the Basin come back to life as observed in the Atchafalaya but that goal will only be achieved through direct struggle with capitalist infrastructure like the BPP.

Conclusions

As more deltaic wetlands are exhausted globally, more threatening and frequent storms break through with catastrophic effects. Capitalism’s continued exhaustion of ‘cheap labor and energy’ pushes both humans and ecosystems towards collapse. As biodiversity loss and toxification continue to intensify in deltas, ecosystem collapse has the potential to ‘spike’ similar to how bee colonies collapse from accumulated neonicotoid pesticides and insecticides. As planetary boundaries are transgressed through climate breakdown, negative value produces forms of work and energy that are hostile to capital accumulation both in human and non-human natures. These creation and destruction cycles are a response to their own exhaustion. [50] As shown by superweeds not responding to industrial herbicides, movements must inoculate themselves against Capital’s interests. There is little time with accelerated global warming to act, so resistance must be swift in its response to protect ecosystems like deltas, arctic regions, and rainforest. As biodiversity loss increases, the ability for non-human natures to continue to reproduce in ecological cohesive ways that support human life wanes. This crisis must be prevented from unfolding.

As negative value continues to destabilize capital accumulation, a new emancipatory politics is emerging to address transformation in which land, food, water, labor, and all of life is given alternative valuation. [51] In contrast to the capitalist technologies that exhaust their raw materials’ supply and produce over-pollution by their tendency to fill up waste frontiers before locating new ones, class struggles like decolonial anti-pipeline movements create “choke points” in Capital commodity chains on the territorial level. These “choke points” can become important contested sites to build broader class struggle movements. As syndicalist labor struggles build counterpower to restructure production on more working-class terms, decolonial struggles can stop Capital appropriation in extraction zones and develop a reparations ecology. Without expanding frontiers of appropriation, the exploitation zone of labor cannot be maintained for Capital accumulation. From a strategic standpoint, decolonial struggles disrupt Capital by confronting it at its points of extraction and disposal. Resistance makes production less cheap until not only a negative value of profits occurs, but Capital is forced to concede more territory, denying it its commodity frontiers. Resistance makes production less cheap until not only does negative value begin to destabilize surplus value with declining rates of profit, but Capital is forced to concede more territory, denying it its commodity frontiers. As negative value increases the global crises of capitalism through resource depletion, rising production costs, and biosphere destabilization, decolonial struggles against extraction create further barriers to Capital accumulation. Diminishing frontiers become vigorously contested through direct resistance, opening up emergent collective possibilities for a Just Transition. As petroleum industries seek to build more fossil fuel infrastructures in Indigenous, Black, and migrant communities, these decolonial movements are building counterpower to reconfigure production and reproduction toward collective liberation.

This article was revised slightly on March 3, 2019 for better clarity. If you enjoyed this piece we recommend the following related articles: Organizing at the Frontiers: Appalachian Resistance to Pipelines and The State Against Climate Change: Response to Christian Parenti.

Footnotes

- Maldonado, Julie K. 2019. Seeking Justice in an Energy Sacrifice Zone: Standing on Vanishing Land in Coastal Louisiana. New York: Routledge, 2, 37.

- Maldonado, 37.

- Maldonado, 69.

- Maldonado, 37.

- Wescott, W.A. 1992. Deltas as Petroleum Provinces: Past, Present, and Future. Offshore Technology Conference. (posted on onepetro.org)

- Moore, Jason W. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. Brooklyn: Verso, 279.

- Maldonado, 2.

- Maldonado, 39

- Maldonado, 43.

- Maldonado, 52.

- Maldonado, 85.

- Maldonado, 91.

- Baurick, Tristan. 20 November 2018. Coast Guard Orders Taylor Energy to Stop 14-Year Oil Leak. The Times-Picayune. (posted on nola.com)

- Davies, Thom. 7 November 2017. Toxic Geographies: Chemical Plants, Plantations, and Plants That Will Not Grow. (posted on toxicnews.org)

- Fanon, Frantz. 1963. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press: 37–38.

- The Establishment. 28 September 2015. Know Your Black History: Slave revolts part 1 – Blacks and Native Americans: The Powerful Alliance You’ll Never Learn About in School. (posted on www.afropunk.com)

- Mies, Maria. 1986. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labor. London: Zed Books, 77.

- Moore 2015, 222.

- Morris, Christopher. 2012. The Big Muddy: An Environmental History of the Mississippi and Its Peoples from Hernando de Soto to Hurricane Katrina. New York: Oxford University Press, 161.

- Morris, 161, 163.

- Davies.

- Taylor, Dorceta E. 2014. Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility. New York and London: New York University Press, 20.

- Becker, Sam. 19 June 2018. Cancer in the U.S.: 15 States with the Highest Rates of Diagnosis. (posted on cheatsheet.com)

- Taylor, 22–24.

- Moore 2015, 279.

- Maldonado, 92.

- Maldonado, 71.

- Yeo, Sophie. 9 November 2018. For Communities of Color, Nearby Industry Leads to Pollution but Not Employment. Pacific Standard. (posted on psmag.com)

- Stop the Bayou Bridge Pipeline. (posted on nobbp.org)

- The Bayou Bridge Pipeline. (posted on nobayoubridge.global)

- Moore, Sheehan. 16 July 2018. Indigenous and Environmental Water Protectors Fight to Block Louisiana Pipeline. (posted on wagingnonviolence.org)

- Hall, Rebecca. 2016. Caring Labours as Decolonizing Resistance. Studies in Social Justice, Vol. 10, No. 2 (December), 220–237.

- Morris, 167.

- GJEP Staff. 18 December 2017. With Tribal Blessing, Louisiana Activist Buys Land in Path of Proposed Bayou Bridge Pipeline. (posted on globaljusticeecology.org)

- Kelly, Sharon. 22 August 2018. First Felony Arrests Near Bayou Bridge Construction Made Under New Louisiana Law Penalizing Pipeline Trespass. (posted on desmogblog.com)

- Dermansky, Julie. 11 October 2018. Despite Lingering Land Dispute, Louisiana’s Bayou Pipeline is Nearly Complete. (posted on desmogblog.com)

- Reid, Lauren. 17 April 2018. Oil and Water: ETP and Sunoco’s History of Pipeline Spills. (posted on greenpeace.org/usa)

- Dermansky.

- Baurick, Tristan. 6 December 2018. The Times-Picayune. Louisiana Judge Rules in Favor of Bayou Bridge Pipeline’s Seizure of Private Land. (post on nola.com)

- Moore 2015, 278.

- Maldonado, 105.

- Maldonado, 104.

- Velednitsky, Stepha. 31 October 2017. The Case for Ecological Reparations: A Conversation with Jason W. Moore. (posted on edgeeffects.net)

- Patel, Raj and Jason W. Moore. 2017. A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things. Oakland: University of California Press, 207.

- Velednitsky.

- Out of the Woods. 22 May 2014. Disaster Communism Part 3 – Logistics, Repurposing, Bricolage. (posted on libcom.org)

- Association of States Wetlands Managers. Carbon Sequestration. (posted on aswm.org)

- Renfro, Alisha. 7 May 2018. A Tale of Two Basins: Why One is Thriving While the Other is Dying. (posted on mississippidelta.org)

- Renfro.

- Moore 2015, 283–286.

- Moore 2015, 290.