By Black Rose/Rosa Negra Burlington

When the industrial age began, working people had no protection against exploitation by their employers. Ten, twelve, and even 14-hour days were common, and a six-day week was the standard. Economists at the time stated that it was a matter of nature that wages would tend towards the bare minimum necessary to support life and that child labor was an inescapable fact of the world. While capitalists would love for us to believe that it was their innovation and generosity that changed all this, they do so to obscure the fact that it is mass movements of working people that have been responsible for every major improvement for workers.

In 1884 a group of the largest trade unions set May 1, 1886 as the day by which they would aim to have won the eight hour workday. In addition to the mainstream unions, socialists and anarchists joined in. Anarchists are well known for being critical of reformism in the political sphere, but they supported the struggle for the eight-hour day because they saw it as a revolutionary step forward on the road toward building a movement that could end class society once and for all.

Capitalists live off the work they don’t pay us for – where else does profit come from? They gain their social power by owning the wealth, machines, and land the rest of us are deprived of. The rest of us can only survive by selling our labor however we can. The value of the wages that our bosses pay us is always less than the value our work creates for them. That extra value, stolen from the sweat of our brow, is the profit that fuels the entire system.

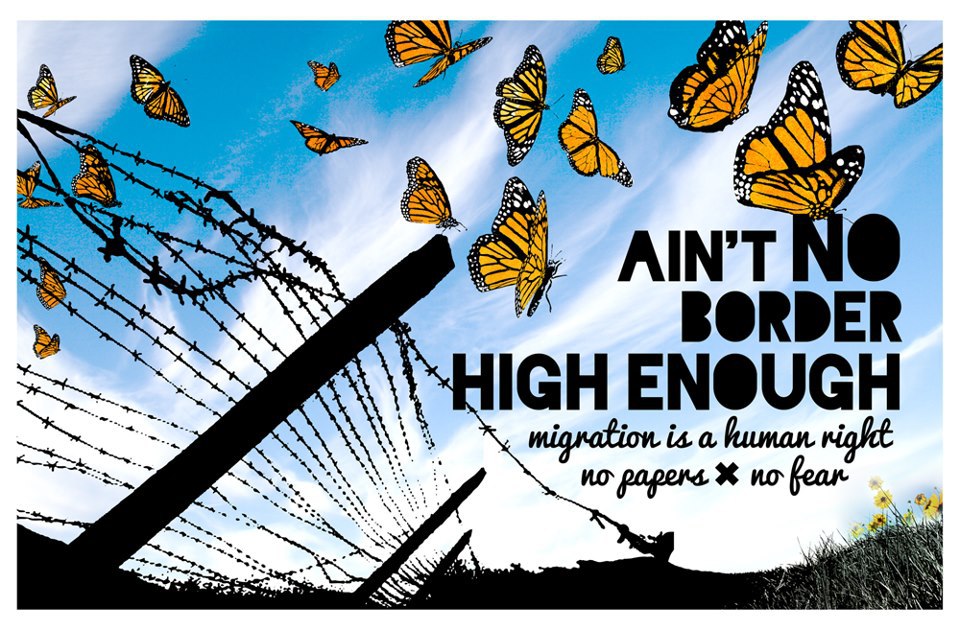

For capitalists, the most reliable way to increase their profits is to reduce their labor costs. They can automate production, reducing the skill needed to create products and making workers more easily replaceable. They can move factories to new locations where wages are lower: that’s why we saw factories move from northern cities like Chicago to the deep South, where the cost of living was lower and there were few unions, and eventually to Mexico and overseas. And for businesses that can’t easily move overseas they rely heavily on workers who have the least ability to stand up for better wages and working conditions: undocumented immigrants.

One of the most ingenious tactics capitalists developed to keep their profits high was to divide workers and pit them against each other. Starting with chattel slavery in the 17th century pitting Black workers against white workers, the owning class has always sought to split up working people by race, gender, language, national origin, and sexual orientation, hoping workers would fight each other instead of their common enemy.

But such tactics weren’t working against the eight-hour day movement, which knit together people of all nationalities and industries, including skilled and unskilled workers who typically did not organize together. Massive strikes spread across the United States on May 1st in 1886. Some of the largest crowds marched in Chicago, home to thousands of radical immigrant organizers. The strikes continued for the next few days, when on May 3rd several striking workers were killed by police, leading to a massive rally at Haymarket square the next day. At this rally, an unknown person threw a bomb into the lines of police, leading to the death of seven policemen and four protesters killed by the police’s ensuing gunfire. Afterward, eight anarchist organizers were tried for conspiracy. They were convicted even though there was no evidence linking them to the crime: it was their beliefs that were on trial. The state wanted to make an “example” of them, to hurt the radical social movements the capitalists feared so much.

Four were sentenced to death by hanging, despite worldwide calls for clemency and outrage at the unfairness of the trial. One of condemned, August Spies, told his executioners at the gallows: “the day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!” May 1st, also known as “May Day” and “International Workers’ Day” is celebrated to commemorate the Haymarket affair and the struggle for workers’ rights.

The American working class was once one of the most militant in the world, and we still enjoy the fruits of their struggles. But there has been a war on our historical memory to erase our radical heritage. That is why nearly every nation celebrates May 1st as “Labor Day” except the United States, the very nation where the day earned its meaning. That is why we must struggle to rebuild the labor movement here and across the world. The never-ending attack on organized workers has left us with unions that are reactive, bureaucratic, and largely unable to maintain the victories they had won decades ago. We need the spirit of 1886 now more than ever.

Immigrants, and especially undocumented immigrants, bear the worst brunt of exploitation by our economic, political, and white supremacist system, so it’s inspiring to see Latinx workers organize to fight back using a day linked to the struggle of immigrant workers so many years ago.

The hour is late. Capitalism continues to spin a web of chaos across the globe that connects such disparate problems as climate change, poverty, war, and terrorism. We need democratic, grassroots unions in our workplaces, schools, and neighborhoods. And above all we need social movements that connect diverse communities and political struggles and are strong enough to wrest power from those at the top and return it to the people.

Black Rose/Rosa Negra is a nationwide federation of anarchists working to do just that. We are an organization of active revolutionaries who share common visions of a new world — a world where people collectively control their own workplaces, communities and land and where all basic needs are met. Learn more at blackrosefed.org.

Twitter: @BlackRoseBTV / Facebook: @brrnburlington