By BRRN Radical Ecology Committee

Climate alarms are going off all over Earth, from the devastating wildfires that have raged recently in California to the mass-bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef, the warming of Antarctica from below, and the continued melting of Greenland, even in winter. In August of last year, 2017 was found to be the hottest year on record without an El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) event, a cyclical phenomenon which periodically warms the Pacific Ocean, while the past four years (2018 included) have been the hottest on record.

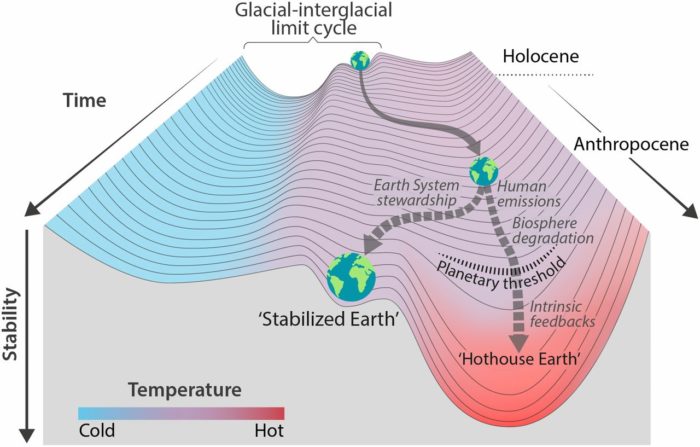

Aptly summarizing our current predicament, Will Steffen and colleagues published “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene” in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in August 2018. The authors describe the risks posed to the “Earth system” by biosphere degradation and the surpassing of environmental thresholds beyond which feedback loops such as reduced albedo effects (from lost ice and snow cover) and increased emissions (from forest fires, lost phytoplankton, and/or liberated methane) render global warming a self-perpetuating phenomenon. These conditions would result in the irrevocably infernal conditions of an imagined “Hothouse Earth.” (See the image below for a visual representation.) Steffen and colleagues are clear about the implications of this framing: “Collective human action is required to steer the Earth System away from a potential threshold and stabilize it in a habitable interglacial-like state.”

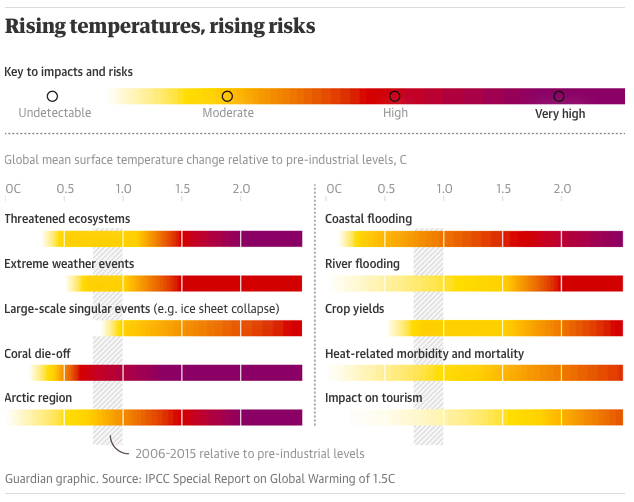

Besides this infamous “Hothouse Earth” paper, several other new studies have illuminated the proverbial sword of Damocles hanging above us: in its October 2018 report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concludes that we have at most 12 years to prevent catastrophic climate breakdown, defined as an exceeding of the globally agreed-upon target of an 1.5-2°C (2.7-3.6°F) increase in average global temperatures since the onset of industrial capitalism. Since the pre-industrial age, Earth has warmed by more than 1°C (1.8°F), so we are already on the knife’s edge. As the global temperature rises, risks to humanity and the rest of nature rise in tandem. See the Guardian graphic below for an illustration of some of the relationships between these risks.

In light of such cumulative risks, which the U.S. climatologist Michael Mann has likened to traversing a minefield—“The further out on to that minefield we go, the more explosions we are likely to set off”—the new IPCC report emphasizes the stark terms of the tasks before us.

“To keep warming under 1.5°C, countries will have to cut global CO2 [carbon-dioxide] emissions 45 percent below 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero by around 2050, the report found […]. To stay under 1.5°C warming without relying on unproven CO2 removal technology means CO2 emissions must be cut in half by 2030, according to the report.”

In November 2018, the World Meteorological Organization published a report which concludes that the world is currently on course for at least 3-5°C (5.4-9°F) of warming. At the same time, the United Nations reported that the world must triple its efforts to prevent climate tipping points themselves triggered by global warming from causing climate breakdown to becoming unstoppable: in other words, to avert “Hothouse Earth.” Meanwhile, a new study in Nature Communication finds that averting warming of 1.5°C—though a goal “at the extreme end of ambition”—is still possible by means of an immediate phaseout of fossil fuels “across all sectors.”

Capital Accumulation and the “Treadmill of Production”: Drivers of Climate Catastrophe

Whereas the risks posed by global warming and mass-extinction are extremely serious, it is very clear that global capitalism has no solution to these burning problems—precisely because “[e]xtinction lies at the heart of capitalist accumulation.”[1] While Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Mohammed bin Salman, and Jair Bolsonaro shamelessly seek to extract the maximum amount of remaining profit possible from the working classes and a ravaged biosphere, Democrats in the U.S., even the most ‘progressive’ among them, have no strategy for mitigating climate change. Many seem to forget how much Barack Obama’s own ecocidal legacy anticipated the Trump administration’s horrific climate-denialism and its aggressive legal strategy to benefit industry by rolling back environmental laws.

The problem is capitalism, or the “treadmill of production”, which brings together Capital, the State, and business unions* to enshrine economic growth as society’s principal consideration and value. This treadmill of production gives “value” solely to what can be financed and commodified for market exchange and profit. According to world-ecology theory, this valuation operates along a binary logic that separates Society and Nature, in which what is considered part of Nature, mostly the work and energy of “women, nature, and colonies,” are considered “free gifts” to be appropriated for “cheap” use. The waste and unpaid other costs of this appropriation of human and non-human natures continue to go uncompensated along racial, patriarchal, colonial, and ecological lines. The alliance between Capital, the State, and business unions operate in collusion to maintain and expand these “appropriation zones” allowing for the cheap commodification of food, land, labor, lives, etc. for market profits. The treadmill must constantly expand these frontier zones of appropriation to avoid declining rates in profit that would result in the bankruptcy of firms, mass-unemployment, and political instability.

Some primary crises within global capitalism include resource depletion, rising costs of production/overaccumulation of capital, and the destabilization of the biosphere and biological health. Negative-value situates these three problems into a unified framework. They represent “a bundle of contradictions within capital that provide fertile ground for a new radical politics that question the practical viability of value and nature in the capitalism world-system.”[2] For this reason, possible solutions to the terminal climate catastrophe threatened by capitalism will have to critically analyze how and why these systemic dynamics co-produce, perpetuate, and govern climate breakdown. Above all, viable solutions must inspire appropriate remedial action to prevent the worst of global warming from taking place. To decelerate this “treadmill of production” and qualitatively transform social production/reproduction, we must build popular movements that challenge this capitalist drive towards accumulation and extinction. We must seek to dismantle the dominant structures that maintain and expand market frontiers through theft and for profit. Our organizing focus will require intervention at the “choke points” of capitalist re/production and their relation to the ecological “fault lines” of climate breakdown.

Avoiding “Hothouse Earth” entails undermining the “cheap natures” model of production and reproduction by mobilizing the until-now latent concept of negative-value. Negative-value creates a barrier to Capital. In destabilizing surplus value (profits), negative value makes possible a new radical politics, which values food, labor, nature, etc in emancipatory and reparatory ways.[3] To move towards this revolutionary alternative valuation of life, which must include a Just Transition, will require that we build rather than destroy. In other words, it is essential that we emphasize mutual aid and learning from different struggles around the world, so as to generate innovative approaches and repurpose local and bio-regionally based ones to construct this viable alternative. Not only must we create a platform of critique and catastrophe, we must strategically nurture liberation struggles, consolidate our efforts through cross-pollinations across the broad working class, and militate for practical demands and solutions that challenge the pseudo-answers offered by the “treadmill” and its advocates.

Toward this end, we wish to explore a number of potentially effective systemic strategies for climate justice here, with an eye to the fundamental question of how we can actually avoid the specter of “Hothouse Earth.” Our perspective favors ecological restoration, green syndicalism, “natural geo-engineering,” and a self-managed decline of the fossil-fuel economy.

*Business unions include many trade unions, whose bureaucratic leadership mediates between workers and bosses, brokering contracts without direct participation of rank and file workers. These union “leaders” have a strategy of cooperating with the capitalist class, often making decisions that are contrary to the interests and demands of workers and ecology.

“Radical Realism”: Strategies for Avoiding “Hothouse Earth”

Above all, we want to review the contributions to this most pressing of tasks made by the contributors to “Radical Realism for Climate Justice. A Civil Society Response to the Challenge of Limiting Global Warming to 1.5°C,” which was published in October 2018 by the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

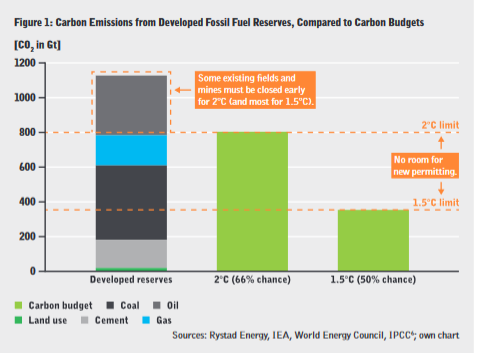

First, in “A Managed Decline of Fossil Fuel Production,” Oil Change International outlines the three principal choices lying before us: managed decline, unmanaged decline, and climate catastrophe. They stress that we must opt for managed decline, a strategy that requires the simultaneous, immediate end to all exploration and expansion of the fossil-fuel industry, together with the closing-down of many existing fossil-fuel production fields and mines, especially coal mines. Oil Change International asserts that, while “some” of these mines and fields would have to be closed to meet the 2°C target, most will have to be shuttered to avert 1.5°C. See figure 1 below.

Oil Change International clarifies that, lacking an outright ban on fossil-fuel exploration and extraction, the world’s so-called “carbon budget” for avoiding dangerous global warming will be surpassed due to the emissions that will be “locked-in” by new projects that can be anticipated (10, 12). Essentially, as the global capitalist economy depends on endless expansion, its energetic underpinnings must be shut down now. As part of the ban they favor, the authors from Oil Change call for an expeditious decline in carbon emissions in line with the trajectory demanded by the latest IPCC report: a halving of global emissions by 2030, and zero by mid-century (11; see figure 3 below).

They support social movements calling for the managed decline of fossil-fuel supply, envisioning that energy corporations “might go bankrupt and investment capital be destroyed” (13). Though this process will surely be disruptive, Oil Change International likens it to a medical regimen, stressing that prevention of the worst of global warming is preferable to attempting to treat as unmanageable a problem as the destruction of the climate commons. They recommend supply-side restrictions of fossil-fuel supply, including on its expansion, such as through the suspension of the massive State subsidies provided for energy corporations, which ensure the profitability of such extractive enterprises, and bans or moratoria on further development (14-15). Together with providing humanity and nature a good chance of avoiding global climate catastrophe, such a program would imply the halting of activities that violate the human rights of poor, racialized, and indigenous communities negatively affected by such extraction. At the same time, a just transition is necessary for those workers currently employed in the fossil-fuel industry, and though Oil Change International mirrors the Heinrich Böll Foundation’s social-democratic politics here by anticipating that financial capital plays a part in this transition, we advocate a green-syndicalist approach, stressing the need to overthrow the labor hierarchies which limit decision-making power in the realm of production, as the best way out. We will return to our favored green-syndicalist strategy in more detail below.

Also in “Radical Realism for Climate Justice,” Christian Holz finds that the global carbon budget for avoiding 1.5°C becomes much more restrictive, if we assume that different technologies for carbon dioxide removal (CDR), such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) or direct-air capture (DAC), will not work at scale (8). According to Holz’s calculations, we must begin a 5-9% reduction of emissions annually by 2025 to stay within the boundaries of 1.5°C—and the author clarifies that such a negative emissions-trajectory is historically unprecedented (13)! Consistent with the model of “contraction and convergence” that has guided climate justice frameworks, Holz underlines the “dual obligations” that countries have toward mitigation of climate change in the domestic and international spheres (19), and he suggests the importance of limiting economic growth for achieving such ends (21). He states that the restoration of existing forests is preferable to mass-afforestation for many reasons, and he suggests that this bio-regeneration can take place on lands that are freed up by the reduced use of cattle and other livestock that would follow from a generalized shift toward plant-based diets (12, 17). This alternative would also follow from the end of the “cheap food” model based on factory farming, industrial livestock, and industrial monoculture agriculture. Like plantation forestry, which seeks to plant trees of uniform species to maximize rapid production and commodification of wood fiber, the ‘cheap food’ model of industrial mono-agriculture, which relies heavily on constant inputs of chemical fertilizers and pesticides drawn from synthesized petroleum derivatives, seeks to expand agricultural production on less fertile and nutrient-depleted land. Genetically modified crops are grown in arid, depleted soils with the help of these artificial fertilizers in the attempt to overcome barriers for the sake of accumulation, regardless of the ecological implications.”[4] Both industries’ destruction of biodiversity is engineered to standardize production and expand capital accumulation.

As Tony Weiss suggests in The Ecological Hoofprint: The Global Burden of Industrial Livestock, the extinction of species through biodiversity loss, a key component in climate breakdown, is intimately bound up with the accumulation of capital. The flip-side of “de-faunation” through biodiversity loss is the “commodi-faunation” through the capitalist treadmill. The acceleration of ecocide follows from the relations of capitalist crisis as they move through the web of life, from the biosphere to animal and human bodies to the capitalist land transformations. Specifically, Weiss investigates the global rise in livestock production since the 1970s. His powerful formulation of capitalist-crisis in world-ecology explore how the valuation of extinguished species and commodified animal products are bound together as specific bundles of human and extra-human natures towards greater capital accumulation. One part follows the necessary human labor and raw materials to the meatpacking plants and factory farms. The other part exterminates life, following the capitalist law of value to its conclusion.[5] This is a salient example of how capital accumulation is not only productive, but it is also necrotic, unfolding through a slow violence that devalues and devours life.[6]

In contrast to this accumulation drive towards planetary extinction through global warming, Mariel Vilella outlines how the implementation of a “zero-waste circular economy” can help with crucial goals of the climate-justice movement. In place of the existing “linear economy” characterized by planned obsolescence, waste, and mass-carbon emissions, a circular economy strives for zero waste and zero emissions (9). The idea is that such a model of zero-waste “ultimately result[s] in less demand for virgin materials whose extraction, transport and processing are major sources of greenhouse gas [GHG] emissions” (11; see figure 2 below).

Characterized by the use of compost and agroecological practices in place of the industrial-scale application of pesticides and petrochemical fertilizers, a zero-waste circular economy contributes to the closing of the nutrients loop (15). An important difference between the existing capitalist economy and this zero-waste circular alternative is that the latter would incorporate product bans, most ideally along the radical lines delineated by the eco-socialist Richard Smith’s “deindustrialization imperative,” which prescribes,

“drastically retrench[ing] [or diminishing] and in some cases shut[ting] down industries, even entire sectors, across the economy and around the planet – not just fossil-fuel producers, but all the industries that consume them and produce GHG emissions – autos, trucking, aircraft, airlines, shipping and cruise lines, construction, chemicals, plastics, synthetic fabrics, cosmetics, synthetic fiber and fabrics, synthetic fertilizer and agribusiness CAFO [concentrated animal-feeding] operations, and many more.”[7]

Though Vilella does not discuss Smith or his radical eco-socialist proposals explicitly, Smith’s advocacy of collective and democratic economic planning to manage this critically needed socio-ecological transition harmonizes with Vilella’s recognition that a zero-waste future must be a participatory project of workers and communities alike, if it is to be adopted at all (19). The potential reductions in emissions that could be achieved through such shifts would be substantial (21).

Meanwhile, in “Re-Greening the Earth,” Christoph Thies describes how the restoration of existing global ecosystems could “fix” much of the carbon that has been emitted historically by industrial capitalism within a matter of decades (10). Essential elements of this vision include the following:

“Stopping deforestation, allowing forests to recover some of the deforested areas, protecting ancient forests from logging, and allowing managed forests to grow back towards their natural growing stock and native tree composition.” (11)

With reference to data from German forests, Thies shows that, the greater the share of forest protected from extraction, the greater the ecosystem’s carbon uptake. That worsening global warming would undercut the great potential for this restorative role underscores the gravity of near-term deep emission cuts, in accordance with the latest science (13). The author spotlights respect for indigenous peoples within the cooperative coordination of reforestation and the restoration of forest biomes in tropical and temperate regions to help solve the climate crisis as well as restore biodiversity and ameliorate soil and water problems alike (14, 19). Admittedly, it is challenging to imagine any of this being practiced in Brazil and the U.S. at this time, ruled over as they are by mutually reinforcing conservative authoritarians—Bolsonaro and Trump, respectively—who deny the existence of environmental ills altogether.

“Natural” Geo-Engineering?

The truth is that the Earth is already much too overheated, owing to overconcentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and it must be cooled, with excess carbon dioxide safely sequestered. Yet paradoxically, abolishing fossil fuels would by itself cause more warming in the short-term, because the industrial emission of these pollutants also distributes aerosols into the atmosphere that artificially cool average global temperatures. This difficulty has led commentators such as David Spratt and Philip Sutton to effectively endorse artificial geo-engineering schemes, the newest “frontier” for techno-capital backed by the Trump administration, that are designed to directly cool the planet.[8] Yet recent research in Nature finds that the idea of artificially creating a sulphate-particle “veil” in the stratosphere as a means of reflecting sunlight away from Earth to mitigate the greenhouse effect would have unacceptably adverse effects on agricultural production. Even David Keith, one of the world’s most prominent geo-engineering enthusiasts, has acknowledged that the closest analogue to artificial geo-engineering schemes is nuclear weapons.

This conundrum brings to mind Troy Vettese’s recent assessment of the “democratiz[ing]” possibilities of “Natural Geo-Engineering” in New Left Review. Vettese explores the “Little Ice Age” experienced during the 16th-19th centuries CE: due to European colonialism’s genocide of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, “[b]otanical regrowth on a bi-continental scale sequestered between 17 and 38 gigatonnes of carbon, lowering the store of atmospheric CO2 by up to 10 parts per million (ppm).” In parallel, “[t]he collapse of [Stalinist] forestry and agriculture in the 1990s allowed the forests in Russia’s European half to absorb more carbon, increasing by a third.” Vettese’s proposal therefore is to consciously induce a “bloodless second Little Ice Age to avert a capitalist climatic Armageddon”—this time without genocides. Asserting that land will be a primary factor in the struggle for an ecological transformation of global society, Vettese describes the land-intensive goals of creating renewable-energy systems and setting aside approximately ‘half of Earth’ for habitat protection, as E. O. Wilson, among others, has advocated as a means of addressing the global climate and extinction crises (66). Precisely how much land will need to be dedicated to renewable-energy infrastructures will have a lot to do with the overall level of energy use in a given society, together with efficiencies (80).

Yet land is also central to Vettese’s own project of “natural geo-engineering,” by which he means a global transition to organic veganic agriculture, implying the restoration, rewilding, and reforestation of approximately 80% of the 5 billion hectares of land currently dedicated to pasture and agriculture (83-85). For even one-fifth of these 5 billion hectares to be successfully reforested, this by itself could decrease the atmospheric carbon concentration by an estimated 85 ppm, “bringing it to a much safer range in the low 300s ppm,” from the current 410 or so (84). Vettese anticipates that such mindful shifts in agricultural and land-use practices, as well as the redesigning of cities to address car-centricity and urban sprawl and the reducing of air travel, could provide new jobs for those workers displaced by the requisite closing-down of the fossil-fuel industry, and he looks for inspiration to Cuba’s Período Especial during the post-Soviet era, when petroleum and its derivatives, including petrochemical fertilizers, suddenly became unavailable on the island, leading to creative responses which remain highly relevant today. Like Mariel Vilella in “Radical Realism for Climate Justice,” Vettese suggests that the prospect of ecological living combined with high human welfare will likely require the rationing of resources “for the sake of fairness and efficacy” (85).[9]

As Vettese does not directly address the aerosols paradox in terms of short-term warming, we presume that this strategy of “natural geo-engineering” is meant to be taken together with “ecological restoration,” as outlined by Thies above, as a response to this problem as part of the overall struggle to prevent the Earth’s overheating in a “green” fashion. We are unsure if this response would be adequate, and invite comment on the question.

Green Syndicalism: For Worker and Community Control

So we have several plans to set into play, and a rapidly diminishing window of time within which to realize them. Yet we do not think these vitally necessary projects will be implemented from above “before the spark reaches the dynamite,” in light of the prevailing dominance of far-right, science-denying politicians on the international stage, as well as the function the State plays in fundamentally facilitating the expansion of capital, itself a primary obstacle in the struggle against the specter of “Hothouse Earth.”

According to the analysis of green syndicalists, ecological destruction and eco-crises emerge and persist precisely because of the “restriction of participation in decision-making processes within ordered hierarchies,” with the capitalist workplace being principal among these.[10] Environmental destruction continues because people’s “capacities to fight a coordinated defense of the planet’s ecological communities” has been weakened, for any number of reasons.[11]. As long as workers merely execute the orders of the bosses, which themselves follow the “logic” of capital, and as long as class hierarchies exist, the environmentally destructive outcomes of production cannot be redressed. Instead of the often-juxtaposed choices of “jobs versus environment,” or “environmentalists versus workers,” green syndicalists suggest a crucial theoretical and organizing reorientation to an opposition between “those who defend the conditions for a possible and desirable life” and those who do the opposite.[12] As such, green-syndicalist strategy recommends alliances among workers, communities, and youth for mass-noncooperation: recasting bosses as “ecological thugs”; organizing collective direct action like workplace demands, strikes, and occupations; and transforming social relations according to the principle, “Earth First! Profits Last,” to ensure economic justice and a livable ecology.[13] By inverting the decision-making hierarchies of labor, syndicalism has the potential to create a green world, as bans and moratoria on fossil-fuels, the uptake of renewable energies, and the practice of participatory democracy all open up through the possible mass-coordination of self-organized anti-capitalist, anti-statist resistance.

Drawing from the larger syndicalist tradition, as it is increasingly applicable to “organizing as a class” in 21st century, our broad approach must take into account relations of exploitation and oppressions of class beyond the workplace. While workplace exploitation is centered around the commodification circuit of Capital, the capitalist world-ecology is intimately intertwined and relies on frontier appropriation zones and divisions of labor for its expansion. The appropriation of unpaid prison labor, the theft of land and resources through colonization, and the subjugation of women into domestic labor and care work are just some of the ways capitalism expands accumulation. Insights from Social Reproduction theory suggest that “the production of goods and services and the production of life are part of one integrated process.” [14] This helps clarify that the working class is “everyone in the producing class who has in their lifetime participated in the reproduction of society- irrespective of whether that labor has been paid for by Capital or remained unpaid.”[15] Since oppressive power relations–such as racism, sexism, colonization, among others, combine and reinforce each other, why and how this occurs under capitalism is important. Production and social reproduction are interrelated processes that create this world-ecology of domination, capital, and nature through the web of life. “Organizing as a class” means that diverse people experiencing oppression and exploitation, in overlapping zones of appropriation and commodification, should unite through struggle against the entire capitalist system. By seeking to dismantle divisions within our class, we strengthen our organizing and make it more comprehensive.

Green syndicalism may further involve a two-pronged approach to “organizing as a class.” While workplace syndicalism seeks to build anti-capitalist counterpower through resistance at the “choke points” of industrial production, community syndicalism seeks to do so across neighborhoods and within communities. Housing/anti-gentrification, anti-racist/anti-fascist, and anti-criminalization/anti-deportation, among other community struggles have the potential to create sustainable, mass-oriented infrastructures of resistance. Community syndicalism emphasizes community control and self-management so that practical solutions may be organized by those directly impacted and according to their specific and diverse needs. Territorial struggles like those to pipeline and fossil-fuel expansion or deforestation may effectively employ community-based syndicalist tactics like direct actions, popular assemblies, anti-repression working groups, and mutual aid networks to mobilize mass resistance at these ecological “fault lines” of appropriation.

One relevant example of this emergent trend has been the recent revival of General Defense Committees (GDC) within the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union which seek to develop self-organized campaigns of direct action, solidarity, and mutual aid in community defense of the broad working class. Other important groups with a similar orientation are the Centros de Apoyos Mutuo in Puerto Rico (CAMS) and the Mutual Aid Disaster Relief (MADR) networks that provide needed support, repair, and repurposing within communities impacted by climate disasters. Synergistic possibilities may extend into workers’ councils or self-managed cooperatives of production and distribution, along bioregional lines, as well as popular assemblies promoting self-managed decline. These on-the-ground organizing structures are necessary to nurture in climate-justice movements, like the recent fledgling Extinction Rebellion (XR). XR has called for a Citizens’ Assembly to oversee the observation of its demands, if they are met, for the UK government to “reduce carbon emissions in the UK to net zero by 2025,”and to “take further action to remove the excess of atmospheric greenhouse gases,” without specifying how much this excess is. Demands on the State and Capital must move beyond simple symbolic protest by linking these infrastructures of resistance to those that require broader social transformation and transition to a post-capitalist world.

Strategically building this approach towards worker and community control involves creating a broad anti-capitalist, ecological movement for climate justice. We must seek to prioritize engagement and cross-pollination with non-state, non-business, community-based associations at the grassroots level. This “self-organizing strategy” takes the form of two sets of strategic objectives that sometimes overlap within struggles. “First, resistance objectives which, when carried out, will so weaken the ecocidal ruling class, as to make direct grassroots challenge to its power possible: and second, transition objectives which, when carried out, will launch us on the path towards building a new society.”[16]

Clearly, the primary obstacle to carrying out this most necessary of transitions away from the path of climate destruction is concentrated reaction in the hands of the State, whether we consider the power of Trump, Putin, Xi, bin Salman, or Bolsonaro. As such, we must with steadfastness confront these despots and their opportunistic reformist opponents—so-called “socialist faces in high places”— by reclaiming our “self-organizing” power to promote ecological restoration, a self-managed decline of the fossil-fuel industry, natural geo-engineering and green syndicalism to prevent “Hothouse Earth.” As Huey P. Newton put it, “You contradict the system while you are in it until it’s transformed into a new system.” [17]

If you enjoyed this piece we recommend the following related articles: Decolonize the Frontiers: The Mississippi Delta, Organizing at the Frontiers: Appalachian Resistance to Pipelines, and The State Against Climate Change: Response to Christian Parenti.

Footnotes

1. Justin McBrien. “Accumulating Extinction: Planetary Catastrophism in the Necrocene,” in Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, ed. Jason W. Moore (Oakland: PM Press, 2016), 116.

2. Jason W. Moore. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (Brooklyn: Verso, 2015), 278.

3. Ibid 246.

4. Foster, John B., Brett Clark, and Richard York. The Ecological Rift: Capitalism’s War on the Earth (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010), 65.

5. Moore, Jason W. “Nature in the Limits to Capital (and vice versa).” Radical Philosophy (September/October 2015), 193.

6. McBrien 116.

7. Richard Smith. “Capitalism and the Destruction of Life on Earth: Six Theses on Saving the Humans,” Truthout 10 November 2013.

8. David Spratt and Philip Sutton. Climate Code Red: The Case for Emergency Action (Carlton North, Victoria.: Scribe Publications, 2008).

9. Troy Vettese. “To Freeze the Thames,” New Left Review 111 (May/June 2018), 73.

10. Jeff Shantz. Green Syndicalism: An Alternative Red/Green Vision (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press 2012), 83.

11. Ibid 112.

12. Ibid 113.

13. Ibid 73-83.

14. Meg Luxton, ”Feminist Political Economy in Canada and the Politics of Social Reproduction,” in Kate Bezanson and Meg Luxton, eds., Social Reproduction: Feminist Political Economy Challenges Neo-Liberalism (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), 36.

15. Tithi Bhattacharya, “Introduction: Mapping Social Reproduction Theory,” in Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, ed. Tithi Bhattacharya (London: Pluto, 2017), 1-20.

16. Steve D’Arcy, Environmentalism as if Winning Matters: A Self-Organization Strategy, Public Autonomy. 17 September 2014.

17. Alondra Nelson, Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 63.