by Thomas

Recently during a discus sion on organizing strategy that I was observing, more than participating in, a friend and comrade of mine emphasized the importance of listening in organizing. He wasn’t talking about listening in the sense of listening only to figure out how to market your ideas in more attractive language, or the kind of listening where you pretend to listen so that the other person is more willing to listen to you; he was talking about the kind of listening that attempts to really understand and consider what the person you’re communicating with is saying.

sion on organizing strategy that I was observing, more than participating in, a friend and comrade of mine emphasized the importance of listening in organizing. He wasn’t talking about listening in the sense of listening only to figure out how to market your ideas in more attractive language, or the kind of listening where you pretend to listen so that the other person is more willing to listen to you; he was talking about the kind of listening that attempts to really understand and consider what the person you’re communicating with is saying.

The point he was making wasn’t to submit to someone else’s point of view, instead of trying to impose yours; his point was to recognize that both you and the person you’re dialoguing with are equal human beings with something of value to contribute to a conversation. This doesn’t always mean that we can find common ground in dialogues; but it does mean that we should try to engage in dialogues in ways that open the possibility of finding common ground where it can be found; and where it can’t: clarifying and truly understanding our differences.

At the time, I really appreciated and still appreciate my friend’s emphasis on listening and the role of true dialogue and communication in organizing, which is based on speaking with rather than a speaking to other folks. Therefore, in an attempt to highlight and continue with this discussion, I wanted to draw on Paulo Freire’s fundamental piece on libertarian education, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. It’s not Freire’s only piece of writing; but it is definitely his most widely-read and influential work, and I believe that it has important insights to consider in thinking about how revolutionary consciousness is built: dialogically and in collective struggle.

In the book, Freire emphasizes the importance of dialogue, or “true” communication, along the lines of the type outlined above. He argues that we must avoid what he calls the “banking” concept of Education: “… the ‘banking’ concept of education: in which the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits.”[i] This type of educational approach tries to impose, or simply transfer information as infallible and self-evident correct doctrine. It sees others as passive objects whose only role is to uncritically receive this information. In an organizing context, this attempt to impose information not only is often unsuccessful; but it hinders solidarity and contributes to societal relations of hierarchical domination of “those who know” and “those who follow”. Instead of empowering, it oppresses. Instead of contributing to engagement, critical thinking and initiative; it domesticates, demobilizes and demoralizes.

In contrast, Freire proposes “problem-posing” education, “critical pedagogy”, “education as the practice of freedom”, or “liberating education”: “Liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferrals of information. It is a learning situation in which the cognizable object (far from being the end of the cognitive act) intermediates the cognitive actors…”[ii] In this type of education, the person communicating offers their ideas or others ideas not as doctrine to be accepted; but as something to be considered. The person communicating and the person they are communicating with- in the instance of a conversation- then both dialogue about that which was being communicated. From this dialogue, new knowledge is created: with the affirmation, rejection and/or refinement of old knowledge and the co-creation of new knowledge. Even if the dialogue ends up mostly an affirmation of the participants already held beliefs, it’s still an instance of the co-creation of new knowledge because it’s contextualized in different experiences, interpreted and understood in deeper ways, and shared as a new unifying connection in relation with the other(s) in the conversation.

When organizing directly in dialogue, this means that we come to the conversation with our ideas- derived from reflection on our own experience, study, and practices-, but that we also come willing to listen to, trying to understand and respecting the ideas of those with whom we’re communicating. Our views are put forward as a contribution to the conversation to be considered in dialogue by both parties.

When contributing pieces of writing, sending e-mails, posting on forums, the same concept applies. Although sometimes the conversation can be less direct or may even take place over a more elapsed period of time -by for example, publishing an opinion piece on a website or having a conversation on an internet forum- rather than in an instantaneous face-to-face dialogue, the same approach applies. Even books published hundreds of years ago can be reflected upon and dialogued with (though the author won’t be able to participate beyond what they’ve already written). In regards to our own pieces of writing, the goal is to contribute to an ongoing conversation and reflection. It is to recognize that your piece is only that: a contribution among many before and many that will come after to an ongoing conversation. It will inevitably – to a greater or lesser degree- have elements that move the conversation forward and – to a greater or lesser degree- will have elements that don’t move the conversation forward (and in some cases might even move the conversation backward). However, our contributions must not be thought of as something only to accept or reject, but rather something to reflect upon in relation to our own and our collective praxis.

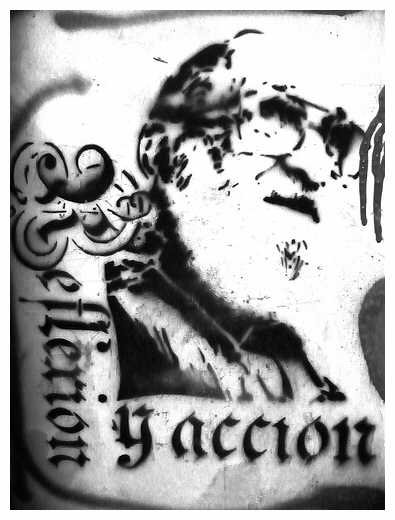

So for those who haven’t heard the term before, what is praxis? It is another fundamental aspect of libertarian educational practice that aims to contribute to revolutionary consciousness. It is fundamental to where conversations should take place: in the context of and with the world around us. With regards to organizing and building revolutionary consciousness, this means an emphasis on dialogue and libertarian educational practice within the context of struggle. Freire describes this dynamic like this: “…praxis: reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it.” [iii] We continue to reflect upon our actions and their relation to the world around us in an attempt to refine and develop the effectives of our actions in their aim of transformation.

Freire contrasts this to both ideas divorced from action and action divorced from ideas: “When a word is deprived of its dimension of action, reflection automatically suffers as well; and the word is changed into idle chatter, into verbalism, into an alienated and alienating ‘blah’… On the other hand, if action is emphasized exclusively, to the detriment of reflection, the word is converted into activism. The latter- action for action’s sake- negates the true praxis and makes dialogue impossible.”[iv]

Therefore in organizing, we must base our initial action on the reflections others and ourselves have had, based on both ours and others’ previous actions and experiences; act in the world concretely in accordance with these reflections; reflect upon these new actions and experiences; act in light of these new reflections; and so on… Praxis bases our reflection upon the world as it is existing, not as it exists. The world never just exists; it constantly evolves and changes through ours and others interactions with it. This means that although we can utilize and learn from the deepest experiences of the past, we must integrate the lessons into our praxis in order to update them to the conditions of our world as it is existing today, tomorrow and beyond.

In the process of the development of revolutionary consciousness through dialogue within praxis, it’s also important to emphasis that a libertarian revolution can’t come about from above and it can’t come about in isolation, it must be collective. As Freire, and as left libertarian revolutionaries have always, argued: “We can legitimately say that in the process of oppression someone oppresses someone else; we cannot say that in the process of revolution someone liberates someone else, nor yet that someone liberates himself, but rather that human beings in communion liberate each other.”[v] This not only reemphasizes the importance of dialogical methods of education, it asserts the importance that these conversations become popularized. If we belief in our ideas, we must find ways to dialogue in different forms with others in struggle or with whom we’d like to discuss the possibility of struggling with. This can be in the form of one-on-one conversations; in the form of written texts; in the form of public forums or workshops; in many, many forms; but ultimately -if we truly believe in the necessity of revolutionary transformation- it must be with others. In addition, it must avoid the pitfalls of prosthelytizing, and instead be based in respectful relations of dialogue and true communication that – in addition to communicating not just expressing our ideas- listens, considers and tries to understand.

Neither my friend, Freire or I advocate that we waste our time with sectarians, those who are dishonest, those who discuss in bad faith or those who dominate and exploit; but rather that we attempt to dialogue with all those in struggle, or potentially in struggle, who we feel are honestly seeking a way to -or who we feel have the potential to start seeking an- end of relations of domination and exploitation that we all face whether in the form of capitalism, the state, or other structures and manifestations of oppression. In doing so, Freire is helpful in reminding us to avoid the “banking” method of education; and instead favor of educational methods based in dialogical reflections and relations. He’s helpful in reminding us to avoid both unreflective activism and baseless verbalism; and instead base these dialogues and communication in the ever-evolving interaction between ideas and practice, or “praxis”. And finally he’s helpful in reminding us that our praxis-based dialogues must be collective if they’re going to contribute towards the kind of consciousness-building and practice development that will lead towards revolutionary possibilities.

[i] Freire, Paulo; Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum: New York; 1970; p.72

[ii] Ibid; p.79

[iii] Ibid; p.51

[iv] Ibid; Pgs .87-88

[v] Ibid; Pgs .87-88