The deep and global history of anarchism in the global south is still being unearthed, recovered and documented. Major strides have been made such as the collection of academic writings Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World: 1870-1940 but there still remains much work to be done. Here we would like to gather a short but certainly not definitive collection of the existing resources that are available for writings on anarchism in Asia. (Updated as of September 2018)

Collections

Bibliography of Western Language Publications on Asian Anarchism – This second edition bibliography includes over 370 references to writings and publications relating to anarchism in Asia. This is a good starting point for research or any deep dive into the history of anarchism in Asia.

Libero International – An English language publication from 1974-1980 by the CIRA-Nappon group based in Kobe, Japan. Spanning six editions the publication sought to archive documents related to anarchism in Japan. Included are pieces relating to Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, China and present day Vietnam.

Recommended Books, Articles and Podcasts

Monster of the Twentieth Century, Kotoku Shusui and Japan’s First Anti-Imperialist Movement, Robert Tierney (2015) – The radical Japanese journalist Kotoku Shusui (pictured), who moved from socialism to anarchism, wrote a seminal critique of imperialism and led the movement against empire in Japan. His work also predates by several years the more well known works by Marxists Hobson and Lenin, but has remained almost unknown in the western left. This books gives an overview of Shusui’s life and work, and includes the first English language translation of his seminal 1901 book. Read the introduction for free here. Listen to an Against the Grain podcast episode interview with the author.

Shifu, Soul of Chinese Anarchism, Edward S. Krebs (1998) – Shifu began his political career as a central figure of in early Chinese nationalist radicalism. But his disillusionment with the republican revolution of 1911 converted him to anarchism and he would go on to became the most well known and important anarchist figure of the period. He founded the Association of Anarchist Communist Comrades and was active is supporting the formation of early labor unions in Shanghai. Read a review of the book here.

Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution, Arif Dirlik (1993) – Anarchism in China emerged out of the early nationalist movement and between 1905 to 1930 exerted a broad influence on Chinese culture and politics. Anarchism was very much at the center of the radical left prior to the rise of the Chinese Communist Party after 1921. Author Arif Dirlik offers the most thorough as well as sympathetic treatment to Anarchist movement of this period. A free PDF is available here and we also recommend this interview with Dirlik as well.

Audio: A Critical Introduction to the Chinese Revolution Interview with Elliot Liu, author of Maoism and the Chinese Revolution: A Critical Introduction, which provides an accessible overview of the Chinese revolution and how it shaped what became Maoist politics. The book was published jointly by anarchist publishers PM Press and Thought Crime Ink in 2016.

Anarchism in Asia – This short overview article focuses on Japanese and Chinese anarchists and is part of a larger collection of documentary history on anarchism.

Review by José Antonio Gutiérrez D. of Anarchism in Korea. Independence, Transnationalism, and the Question of National Development 1919 – 1984 by Dongyoun Hwang. The review discusses the little known history of the Korean anarchist movement and themes of nationalism, transnational alliances, relations with the rising communist movement during the period and more.

Decolonizing Anarchism, Maia Ramnath (2011) – This recent work looks at the history of South Asian struggles against colonialism and neocolonialism, highlighting lesser-known dissidents as well as iconic figures. A free PDF of the book is available here. A critical review is also available.

Bhagat Singh (1907-1931): An Indian revolutionary attracted to both anarchism and Leninism, Bhagat Singh (portrayed in a bust figure below), was a Punjabi Sikh and a follower of the Ghadar Party. Singh gained notoriety when in 1929 he and another comrade exploded bombs inside the Delhi Central Legislative Assembly while exclaiming “Inqilab zindabad!” (“Long live the Revolution!”). Singh disagreed with Gandhi’s Satyagraha approach, both for its pacifism, as for his concern that it would reproduce class domination. Singh was executed at the age of 23 after assassinating a British police officer, John Saunders, in Lahore after having mistaken him for the British police superintendent. Singh has since been appropriated by the Indian state as an nationalist and anti-colonial figure divorced from his radical politics. Read a celebratory article about Singh here.

Movements and Figures Related to Anarchism and Anarchist Ideas

Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Charted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire, Maia Ramnath (2011) – This volume examines the Ghadar Party, a transnational anti-authoritarian network that fought for India’s liberation from British rule, counting with the participation of many anarchists.

Asia’s Unknown Uprisings, Volume 1: South Korean Social Movements in the 20th Century, George Katsiaficas (2012) – In this volume, Katsiaficas highlights the Gwanju Commune (1980) in South Korea as a popular-liberatory uprising that, though ultimately crushed by the military, was decisive in undermining the ongoing dictatorship. The author also discusses Korean labor, student, and feminist movements against the backdrop of rising neoliberalism. See here for a comparison by Katsiaficas of the Paris and Gwanju Communes.

Asia’s Unknown Uprisings, Volume 1: South Korean Social Movements in the 20th Century, George Katsiaficas (2012) – In this volume, Katsiaficas highlights the Gwanju Commune (1980) in South Korea as a popular-liberatory uprising that, though ultimately crushed by the military, was decisive in undermining the ongoing dictatorship. The author also discusses Korean labor, student, and feminist movements against the backdrop of rising neoliberalism. See here for a comparison by Katsiaficas of the Paris and Gwanju Communes.

Asia’s Unknown Uprisings, Volume 2: People Power in the Philippines, Burma, Tibet, China, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Thailand, and Indonesia, 1947–2009, George Katsiaficas (2013) – In volume 2, Katsiaficas discusses the various “People’s Power” movements that arose in several Asian countries in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, starting with the popular mobilization to overthrow Marcos in the Philippines (1986). The author also discusses popular-insurgent movements in eight other countries, highlighting the demands for democratization (Burma, China, Bangladesh, Indonesia), resistance to colonization and occupation (Tibet), and opposition to despotism (Nepal, Thailand). See a review here.

Daoism and Anarchism: Critiques of State Autonomy in Ancient and Modern China, John A. Rapp (2012) – In this study, Rapp explores Daoism as an anarchist religion, contrasting it with the hierarchies of Confucianism, the Chinese Imperial State, and Maoism alike. The author associates the classical Daoists, Lao Zi and Zhuang Zi (6th and 4th centuries BCE), with advising the nascent Chinese State authorities to abdicate power and thus allow humanity to reconnect with the dao, or natural human solidarity. See a review on Libcom here.

L’Homme et le Terre, Elisée Reclus (1905-8) – In vol. 3 of Humanity and the Earth, Reclus acknowledges Buddhism as an anarchistic “gospel of brotherhood” that proclaims “no more kings, no more princes, no more bosses or judges, no more Brahmins or warriors, no more enemy castes that hate one another, but rather brothers [and sisters], comrades, and companions who work together!” Reclus sees a parallel here with Christianity, in that the Buddha’s radical dharma was institutionalized to legitimize State oppression, much as the message of Jesus the Nazarene was negated through the Roman Emperor Constantine’s official adoption of Christianity. For more details, see here. Similarly, George Katsiaficas recognizes Buddhism and Jainism as egalitarian offshoots of Hinduism.

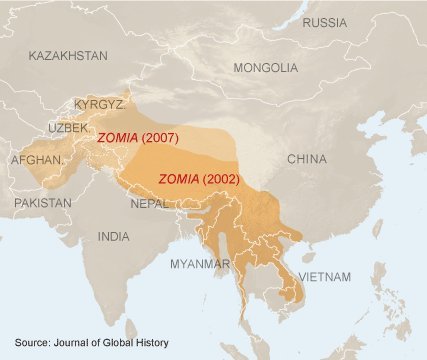

The Art of Not Being Governed, James C. Scott (2009) – In this text, the anthropologist Scott describes the stateless societies of upland Zomia, a 2.5 million-square-kilometer region spanning much of Southeast Asia. The author explains that, rather than represent “left-behind” remnants of a bygone era, the hill peoples of Zomia consciously opted in favor of existence at the margin of the state, or free from its dominion altogether. To do so, Zomians have engaged in foraging, hunting, pastoralism and “escape agriculture” via root-based shifting crops. In addition, such methods can support only small populations, in contrast to the expansive population growth seen in lowland padi kingdoms, where the masses are enslaved to harvest rice and serve a centralized power. See a review here.

Religion Against Religion, Ali Shariati (left) – The principal philosophical influence on the coming of the Iranian Revolution (1979), the sociologist and historian Shariati presented a libertarian interpretation of Shi’a Islam, emphasizing Shi’ism as a religion of martyrdom and mourning. This follows from the historical division between Sunni and Shi’a Islam: the month of Muharram, the first month in the Islamic calendar, commemorates the battle of Karbala (680 CE), where Hussein ibn Ali, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad revered by Shi’ites, was defeated and martyred along with his family at the hands of the Sunni Umayyad dynasty led by Yazd I. Shariati therefore argues that the true essence of Shi’a Islam is in its “red” manifestation (Alavid Shi’ism), as opposed to the “black” manifestation of institutionalized religion, authoritarianism, and despotism (Safavid Shi’ism). Shariati emphasized martyrdom en masse as a means of overthrowing tyrannical regimes such as that of the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. He advocated women’s rights, minority rights, land reform, and direct democracy. This thinker believed that the true meaning of Tawhid (“unity”) was a classless society. See Ali Rahnema’s biography, An Islamic Utopian.

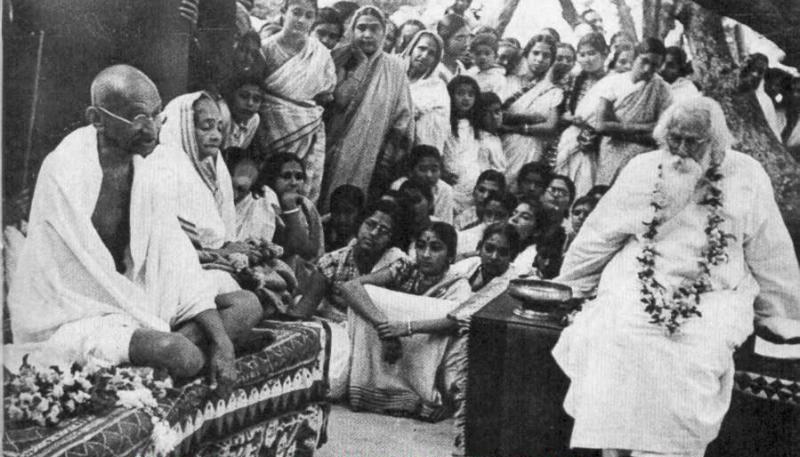

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941): The Bengali poet and novelist Tagore (below, right), considered by Maia Ramnath to be one of India’s “romantic counter-modernists” alongside Gandhi, opposed British rule and emphasized the importance of mass self-organization and -education. The first non-European recipient of the Nobel Prize (1913), Tagore critiqued industrialism, imperialism, and statism while advocating grassroots cooperative rural self-development programs toward the creation of a swadeshi samaj (“autonomous society”) through decolonization. He repudiated his knighthood after the 1919 Jalianwala Bagh (Amritsar) massacre and mediated conflict between Gandhi and the Dalit organizer B. R. Ambedkar. Read Tagore’s “Where the Mind is Without Fear” here.

If you enjoyed this resource page you may also be interested in “Anarchism in Latin America: The Re-Emergence of a Viable Current,” the introductory chapter to Anarchism in Latin America by Angel Cappelletti and translated by Gabriel Palmer-Fernandez.