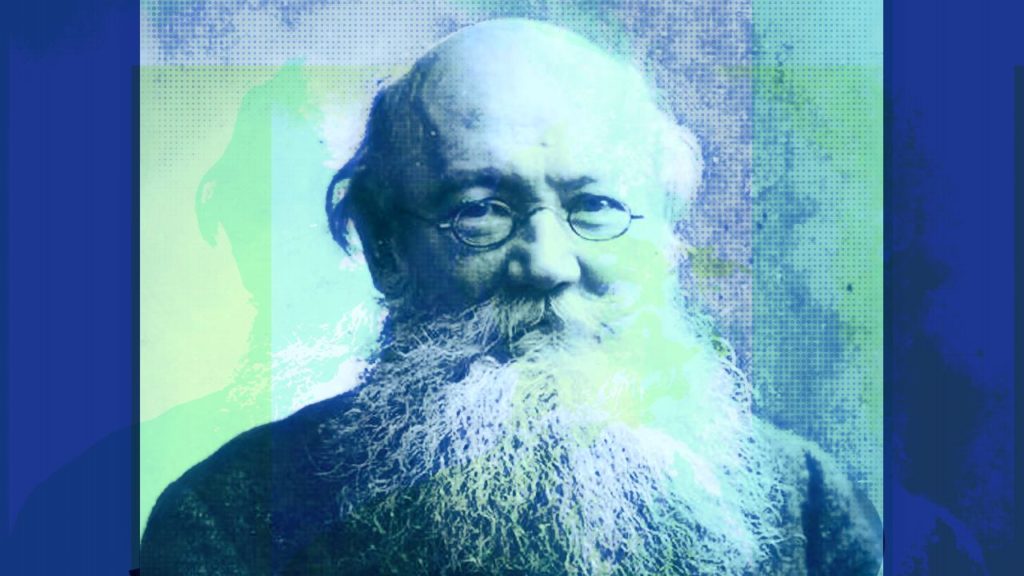

Author of “the bread book” (The Conquest of Bread), Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921) was a leading anarchist intellectual in his time who wrote dozens of books, articles and pamphlets arguing for a from-the-bottom-up socialist vision of society informed by his background as a natural scientist. The newly released Modern Science and Anarchy from AK Press brings together previously unpublished content in English as well as other writings previously only released as pamphlets and articles. Of course, a critical portion of the book which is as relevant as ever is devoted to Kropotkin’s study of the nature and origins of the State and which includes this brief excerpt as part of a larger critique of the state. #TheLeftInPower

Can the State be Used for the Emancipation of the Workers?

By Peter Kropotkin, excerpted from Modern Science and Anarchy

[F]ollowing an error of judgment which truly becomes tragic, while the State that provides the most terrible weapons to impoverish the peasant and the worker and to enrich by their labour the lord, the priest, the bourgeois, the financier and all the privileged gangsters of the rulers—it is to this same State, to the bourgeois State, to the exploiter State and guardian of the exploiters— that radical democrats and socialists ask to protect them against the monopolist exploiters! And when we say that it is the abolition of the State that we have to aim for, we are told: “Let us first abolish classes, and when this has been done, then we can place the State into a museum of antiquities, together with the stone axe and the spindle!” [1]By this quip they evaded, in the fifties of the last century, the discussion that Proudhon called for on the necessity of abolishing the State institution and the means of achieving this. And it is still being repeated today. “Let us seize power in the State”—the current bourgeois State, of course—“and then we will make the social revolution”—such is the slogan today. [2]

Proudhon’s idea had been to invite the workers to pose this question: “How could society organise itself without resorting to the State institution, developed during the darkest times of humanity to keep the masses in economic and intellectual poverty and to exploit their labour?” And he was answered with a paradox, a sophism.

Indeed, how can we talk about abolishing classes without touching the institution which was the instrument for establishing them and which remains the instrument which perpetuates them? But instead of going deeper into this question—the question placed before us by all modern evolution— what do we do?

Is not the first question that the social reformer should ask himself this one: “The State, which was developed in the history of civilisations to give a legal character to the exploitation of the masses by the privileged classes, can it be the instrument of their liberation?”

Furthermore, are not other groupings than the State already emerging in the evolution of modern societies—groups which can bring to society co-ordination, harmony of individual efforts and become the instrument of the liberation of the masses, without resorting to the submission of all to the pyramidal hierarchy of the State? The commune, for example, groupings by trades and by professions in addition to groupings by neighbourhoods and sections, which preceded the State in the free cities [of the Middle Ages]; the thousand societies that spring up today for the satisfaction of a thousand social needs: the federative principle that we see applied in modern groupings—do not these forms of organisation of society offer a field of activity which promises much more for our goals of emancipation than the efforts expended to make the State and its centralisation even more powerful than they already are?

Is this not the essential question that the social reformer should ask before choosing his course of action?

Well, instead of going deeper into this question, the democrats, radicals, as well as socialists, only know, only want one thing, the State! Not the future State, “the people’s State” of their dreams of yesteryear, but well and truly the current bourgeois State, the State nothing more and nothing less. This must seize, they say, all the life of society: economic, educational, intellectual activities and organising: industry, exchange, instruction, jurisdiction, administration—everything that fills our social life!

To workers who want their emancipation, they say: “Just let us worm ourselves into the powers of the current political form, developed by the nobles, the bourgeois, the capitalists to exploit you!” They say that, while we know very well by all the teachings of history that a new economic form of society has never been able to develop without a new political form being developed at the same time, developed by those who were seeking their emancipation.

Serfdom—and absolute royalty; corporative organisation—and the free cities, the republics of the twelfth to fifteenth centuries; merchant domination—and these same republics under the podestas and the condottieri; [3] imperialism—and the military States of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; the reign of the bourgeoisie—and representative government, are not all these forms going hand in hand striking evidence [of this]?

In order to develop itself as it has developed today and to maintain its power, despite all the progress of science and the democratic spirit, the bourgeoisie developed with much shrewdness representative government during the course of the nineteenth century.

And the spokespersons of the modern proletariat are so timid that they do not even dare to tackle the problem raised by the 1848 revolution—the problem of knowing what new political form the modern proletariat must and can develop to achieve its emancipation? How will it seek to organise the two essential functions of any society: the social production of everything necessary to live and the social consumption of these products? How will it guarantee to everyone, not in words but in reality, the entire product of his labour by guaranteeing him well-being in exchange for his work? What form will “the organisation of labour” take as it cannot be accomplished by the State and must be the work of the workers themselves?

That is what the French proletarian, educated in the past by 1793 and 1848, asked their intellectual leaders.

But did they [their leaders] know how to answer them? They only knew how to keep on repeating this old formula, which said nothing, which evaded the answer: “Seize power in the bourgeois State, use this power to widen the functions of the modern State—and the problem of your emancipation will be solved!”

Once again the proletarian received lead instead of bread! This time from those to whom it had given its trust—and its blood!

To ask an institution which represents a historical growth that it serves to destroy the privileges that it strove to develop is to acknowledge you are incapable of understanding what a historical growth is in the life of societies. It is to ignore this general rule of all organic nature, that new functions require new organs, and that they need to develop them themselves. It is to acknowledge that you are too lazy and too timid in spirit to think in a new direction, imposed by a new evolution.

The whole of history is there to prove this truth, that each time that new social strata started to demonstrate an activity and an intelligence which met their own needs, each time that they attempted to display a creative force in the domain of an economic production which furthered their interests and those of society in general—they knew how to find new forms of political organisation; and these new political forms allowed the new strata to imprint their individuality on the era they were inaugurating. Can a social revolution be an exception to the rule? Can it do without this creative activity?

Notes

1. [A reference to the famous 1884 work by Engels, Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State, which argues: “The state, then, has not existed from eternity. There have been societies that managed without it, that had no idea of the state and state authority. At a certain stage of economic development, which was necessarily bound up with the split of society into classes, the state became a necessity owing to this split. We are now rapidly approaching a stage in the development of production at which the existence of these classes not only will have ceased to be a necessity, but will become a positive hindrance to production. They will fall as inevitably as they arose at an earlier stage. Along with them the state will inevitably fall. Society, which will reorganise production on the basis of a free and equal association of the producers, will put the whole machinery of state where it will then belong: into the museum of antiquities, by the side of the spinning-wheel and the bronze axe” (Marx-Engels Collected Works, Volume 26 [London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990], 272). (Editor)]↩

2. [A reference to, for example, Engels’s arguments from 1883 that while he and Marx saw the State’s “gradual dissolution and ultimate disappearance,” the proletariat “will first have to possess itself of the organised political force of the State and with its aid stamp out the resistance of the Capitalist class and re-organise society.” The anarchists “reverse the matter” by advocating revolution “has to begin by abolishing the political organisation of the State.” For Marxists “the only organisation the victorious working class finds ready-made for use, is that of the State. It may require adaptation to the new functions. But to destroy that at such a moment, would be to destroy the only organism by means of which the working class can exert its newly conquered power” (Marx-Engels Collected Works, Volume 47 [London: Lawrence & Wishat, 1993], 10). (Editor)]↩

3. [Podesta were high officials (usually chief magistrate of a city state) in many Italian cities beginning in the later Middle Ages; Condottieri were the leaders of the professional military free companies (or mercenaries) contracted by the Italian city-states and the Papacy from the late Middle Ages and throughout the Renaissance. (Editor)]↩