A decades-long veteran of the Democratic Party explains why elections fail to bring meaningful change.

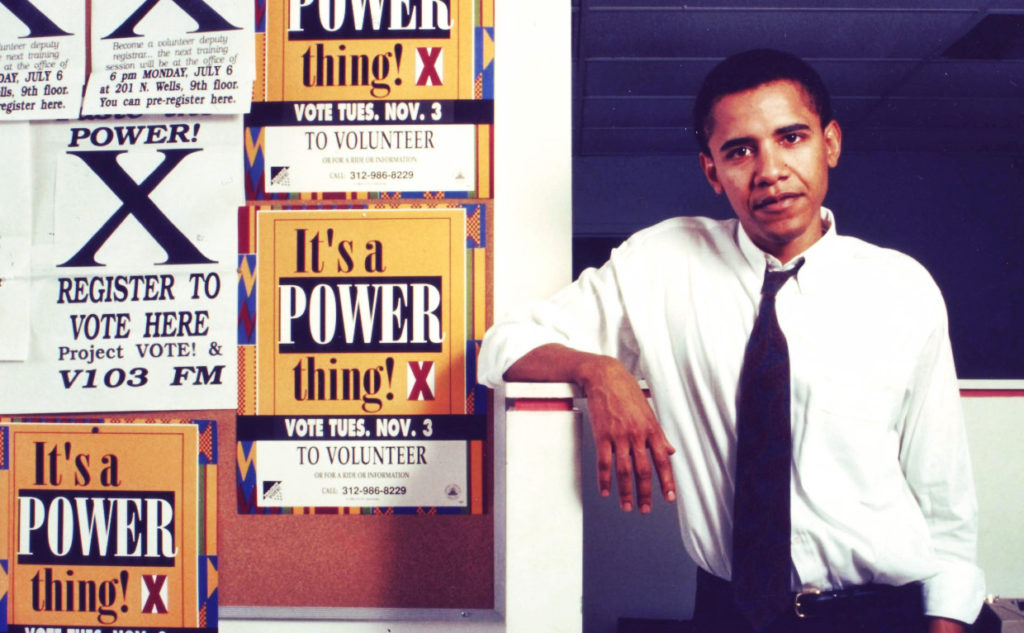

It’s often said that it’s easy for radicals to criticize from the outside, but what about when the critique resonates for someone who is an insider? As a follow up to the publication of “The Lure of Elections: From Political Power to Popular Power” by a group of Black Rose/Rosa Negra authors, we present the experience of an individual we will call “Carlos,” on the dynamics of electoral campaigns. Carlos first became active in politics in his native Puerto Rico and then as a youth growing up in East Harlem where he first registered to vote during a rally at his high school organized by Jesse Jackson and his Operation PUSH campaign. has over 10 years of experience working in progressive electoral campaigns as a professional campaign consultant. He’s worked on national campaigns such as Howard Dean and Obama as well as with progressive local and state candidates running for office in major urban areas on the east coast.

Carlos now describes himself as a “former” campaign consultant as he threw in the towel well before the 2016 election and pursued a different career path. We invited him to share his experience with us on the internal dynamics of electoral campaigns. Here’s what he originally wrote to us:

“Campaigns are designed to strip-mine resources out of communities. Instead of instigating popular movements, they stifle critical examination of power and its inherent abuse within the electoral paradigm. Instead of fomenting social movements, they serve as a cyclical escape valve whose sole purpose is to perpetuate the grip that the status quo has on society”

Note: Out of respect for this interview being conducted anonymously certain details and the names of specific campaigns have been omitted. Additional references have been for individuals and organizations for those who may not be familiar.

BRRN: Can you give us some examples of how campaigns hurt the social movements and organizations that already exist in communities? What did you mean when you said that electoral campaigns are akin to “strip-mining resources out of communities”?

Carlos: The most valuable asset any community has is its human capital. A well-designed campaign aims to matriculate supporters into its ranks and lead them along a prescribed engagement continuum. Electoral campaigns identify supporters and entice them to become activists by engaging in financial contributions, contributions of their free labor as volunteers and most importantly by contributing their most limited and irreplaceable asset: their time. Ultimately we aim to get your vote, but along the way we want you to first become an evangelizer of sorts. We want you to become a human amplifier of the campaign’s sphere of influence. We don’t only want your vote, we want your money, your body, and your soul! We want you to proselytize to the masses the good news that ballot-box salvation is (once again) at hand. At this point, you have become a trustee of the institution of electoral campaigns and as such upon you is conferred the most enviable status of “grassroots community leader”—gatekeeper to the campaign and another handful of votes in the neighborhood.

And if you were with Obama for America (OFA) as a staff member chances are that you participated in training sessions that utilized the Marshall Ganz method for developing a public narrative. OFA organizers would often counsel campaign volunteers to stay away from engaging in discussions about specific issues and instead focus on sharing the “story of self,” the “story of us,” and the “story of now.” This methodology is intended to engage the prospective voter at an affective level much like a 12-step group speaker or a born-again Christian sharing her story of how she found Jesus. And, while I’m not critical of Prof. Ganz for sharing the lessons that he learned under the tutelage of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers, I am critical of the manner that OFA used his methodology to short-circuit a perfectly legitimate way of facilitating the raising of critical consciousness (a long-term proposition) for the short-sighted aim of mobilizing the electorate for an election-night win. That’s not a way to build political sustainability but instead strip-mining votes, in a manner of speaking.

We can surmise that the electoral conflicts that are presented to the voting public more often than not limit their participation to a choice between candidate A and candidate B (first dimension of power). In other words, the voting public does not truly participate in setting the agenda (second dimension of power) as to who they really prefer to have as their representative and what the representation should entail in the first instance. Nor do they examine how they truly feel or made to feel (third dimension of power) about the whole question of a sham participatory democracy. Here their will is invalidated via post-election horse-trading in the name of practical compromises that are supposed to advance the public good – although the scorecard seems to demonstrate a clear advantage to those who wield power.

And sure, there is always the next election, but what then? Another reshuffling of deck chairs on the electoral Titanic? As they say in the hood, don’t hate the player; hate the game.

BRRN: Given the reality of most low-income, Black & Latinx communities and neighborhoods being excluded from politics and decision making, tell about the narratives for political campaigns in these communities, how do they sell their candidacy? What do candidates do to pull them in one more time?

Carlos: In 2013 I consulted for a candidate for NYC council running for an open seat in the Bronx. One of his opponents was the choice of the county Democratic committee who is, by law, supposed to remain neutral during the primaries. However, their chosen candidate received the full support of essentially every member of the county committee as well as the support of the powerful real estate board (REBNY) who had invented a PAC named “Jobs for NY.” Not only did the chosen candidate, with the help of the local political apparatchik, raise the maximum amount of campaign funds pursuant to public campaign finance rules, the independent expenditure group went ahead and spent near $192,000 in support of her candidacy and an additional approximate $11,000 specifically targeted against my client.

In other words, it doesn’t matter that you get throngs of local constituents to donate a paltry $10 each of which are then matched by the NYC Campaign Finance Board. If the opposition is favored by a group like REBNY they’re are going to get an additional $200,000 in spending power. And, that doesn’t even include the benefits of the full organizational support (think campaign volunteers, election day workers, staging sites, etc.) that they get by virtue of being the darling of the county committee and the real estate interest, for instance.

According to the NYC Campaign Finance Board, during the 2013 municipal campaign cycle, Jobs for NY spent just shy of $7 million on behalf of its chosen candidates. How can anyone really believe that the voices of ordinary people have real power when their locally elected representatives are bought and paid for even before they take their oaths of office? If you look at voter turnout in many of those same low-income communities you’ll find that voter performance often hovers at less than 10 percent of registered voters. Not to be confused with the number of eligible voters, only focusing on those who bothered to register and you still sometimes get as low as three percent turnout in a city where elections are determined by who wins in the primaries. The system is not broken, it’s working just as it was designed: to suppress popular participation in the body politic.

BRRN: Often there’s a perception that while national politics are completely dominated by power plays and political expediency, local politics, especially those at the level of city council, are different and there’s greater room for accountability. Having worked on national, state and city level electoral campaigns what does your experience show?

Carlos: In the early 2000s I was just making inroads into Lower Hudson Valley politics. At that time one of the strategic objectives was to wrestle the [NY] State Senate from the hands of Republicans. The 35th district held by Republican, Nick Spano, of Yonkers, was a prime target. I approached the NARAL PAC about getting support for a progressive African American woman who was vying for that seat, Andrea Stewart-Cousins. After an exhausting back and forth the position of NARAL was that they couldn’t support Stewart-Cousins because Nick was pro-choice and they didn’t want to alienate him. Never mind that Nick, as a member of the Republican conference leadership, had always cast his vote during the organizational leadership meeting at the launch of each session in support of a majority leader who was a sworn enemy of the pro-choice movement. But such is the political logic of many a liberal group.

That vignette encapsulates the dilemma that progressives face in getting their chosen candidates elected to local office. We can organize around a progressive platform, recruit, develop, and launch progressive candidates, but if as a condition of getting any of the political “lulus” like a chairmanship or a leadership post, additional staff, or something as inane as a plum spot in the parking lot, they first have to sell their souls to the devil by aligning themselves to the organizational leadership already in place. In those places the money behind the power often comes from real estate industry or one of the many powerful business interests whose access and control of the legislative/appropriation process determines profit margins and windfalls.

BRRN: A lot of losing candidates, especially those running as progressive or left third party candidates, conclude by telling their supporters “this election is only the beginning, we’re building a movement!” Have you ever seen a promise like that be fulfilled? And when people have built movements and won victories for working class people, where have you seen that come from?

Carlos: I witnessed the transition of Dean for America into Democracy for America (DFA) under Howard’s brother, Jim Dean. From the beginning, it hosted something called DFA Night Schools via which it provided lots of useful information to those who were interested in entering politics as progressive candidates even if it meant challenging their local Democratic committee. However, when this was first happening Howard was restructuring the DNC and bringing in The VAN or Voter Activation Network (VoteBuilder) to implement the 50-State Strategy. In the end, that electronic voter file capability strengthens many local committees and makes it even more difficult for true progressive reformers to beat their local machine politicians.

Take a state like NJ where the state Democratic party decides who will have access to the voter file. Even if you are willing to pay for it, it’s up to the party to grant you access. Another reform-intended tactic co-opted by the political bosses. DFA certainly does provide information for the lay political enthusiast to use in her quest for elected office. But again, it doesn’t matter how many progressive candidates there are if the rules are rigged in favor of the status quo. From the moment that new progressive is inducted into public office special interest will bring whatever pressure to bear in pursuit of their goals and objectives.

Then there was Obama for America’s (OFA) transition into Organizing for America following Obama’s win. Whereas Dean’s Democracy for America functioned at arm’s length from the DNC, Obama’s Organizing for America was a ‘wholly-owned and operated’ project of the DNC. It was supposed to help organize and mobilize the electorate to support Obama’s legislative agenda, but as we witnessed, it seemed like the Tea Party ate their cookies and stole their milk money. It was a colossal flop. They tried to resuscitate it in 2013 as Organizing for Action (a 501 c4 org), but any serious post-mortem would conclude that the corpse was DOA by time Sanders announced his intention to run—his candidacy sucked the oxygen out of the room and left OFA and the DNC both gasping for air.

Which brings us to Bernie. Here again, I saw a glimmer of hope due mainly to the gracious acceptance of a self-described democratic socialist running as a mainstream candidate by both Democrats and independents. For many people who had all but given up on the superannuated DNC-RNC quadrennial tango, Bernie was a novelty. He made bold proposals that made the DNC establishment cringe at the thought that their Wall St. bosses were about to pull the plug on them and jump ship to the RNC en mass. But alas, Bernie’s candidacy was thwarted by the powers [of the party].

BRRN: The Obama campaign was a milestone in being perceived as a progressive candidate that was to the left of Democratic Party establishment. It sought to mobilize a young and progressive bases of voters in novel and non-traditional ways. Tell us about what you saw working within this campaign?

Carlos: Around 2006, I was residing in Philly working on some client campaigns in the region when I began to pay closer attention to Barack Obama. As Sen. Harry Reid put it, he was “clean.” I understood what Reid said through the cold lens of political calculus: Obama was an “acceptable,” Ivy League trained, affable African American with a beautiful young family. If we were to break through the racial barrier he was it.

Like [Howard] Dean before him, Obama captured the attention of young America by his sheer novelty as a charismatic African American candidate but also because he, for the most part, was saying the right things. We would later come to once again be reminded of the observation that “they might campaign in poetry but they govern in prose.” After the presidential campaign, Dean became head of the hydra known as the DNC and then after that a shill for the HMO cartels. Obama, who promised immigration reform deported more Latinos than his predecessors, and while he campaigned on closing Guantanamo instead dropped more drone-powered bombs on Muslims than the Republican he ran against.

So, what gives? It seems that no matter how much they genuinely yearn for transformative change once they get into the halls of power they are co-opted into the existing, permanent power-structure.

Robert Caro said it best when he surmised, “We’re taught Lord Acton’s axiom: all power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely…” To my mind, there is a power behind the public face of the electoral process and it is suspect. We need to interrogate that power. After a lifetime of helping ordinary men and women gain access into the halls of power, I look around and wonder is there a better way? I hope so because at this rate we’re killing our planet and our chances of survival as a species today stands in peril.

BRRN: Given this picture of electoral politics, where and how can regular people create meaningful change?

In the final analysis, true and lasting change can only come from efforts that aim to raise critical consciousness without regard to short-term electoral victory. Take a concept like that of Myles Horton’s Highlander Folk School, for instance. They have been facilitating transformative change to people lives in their quest for social and economic justice for decades. It is that sort of model that provides those precious spaces where common people can share with each other their experiences, strengths and hopes so that the great challenges we face today might be conquered.

It is not via the latest slick campaign that we’ll find salvation, but in the empirical praxis that a life of struggle brings to the cold reality of living in the most sophisticated system of oppression known to man. [This is] a social-economic system that banks on the expectation that most people will feel so beaten down by life that they conclude that there is no hope; that there is only surrender to the bosses, the landlord, the state, and hope for a better afterlife. But we know that history has provided instances where ordinary people have challenged that paradigm and discovered in their shared struggle the key to their common salvation. Myles Horton said it best when he said, “Nothing will change until we change—until we throw off our dependence and act for ourselves.” No politician, no electoral victory will ever do that for us.

I still believe in those prophetic words spoken long ago by Frederick Douglass, who understood liberation as a lived-experience. In 1857 he said: “The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims have been born of earnest struggle. . . . . If there is no struggle there is no progress. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” It was true then and it’s still true today. That is my gospel.