This interview looks at the development, history, politics, and legacy of the Lavender and Red Union, an early gay communist political organization that was based in Los Angeles from 1974 to 1977. M., of Black Rose / Rosa Negra, sat down with a former member of the Lavender and Red Union, also briefly known as the Red Flag Union, named Walt Senterfitt in his Boyle Heights home in Los Angeles to see what today’s revolutionaries can learn from their legacy.

We see Lavender and Red’s specific politics as a product of their time and of their relationship to the larger mid-70s US left. While we have important disagreements with the politics of the group, especially the Leninist model of vanguard parties, we do think we can gain from studying the experiences of Lavender and Red Union during their brief life before merger with the Spartacist League in 1977.

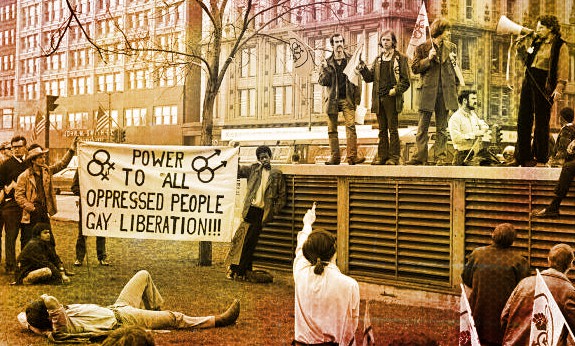

One of the points that came up in the interview multiple times was the perspective that queer people will not be able to win alone: If we want liberation then we will need to fight together in the same struggles as all the other oppressed groups that make up the working class with us. We cannot only focus on building organizations that just address our own concerns or our own narrow community (which the Lavender and Red Union called ‘sectoralism’). This lesson and many of the other points discussed in this interview continue to be of importance for those of us who struggle with pushing back against the liberal, reformist, and class collaborationist tendencies in our movements.

The interview was done for the Turkish queer magazine Kaos GL Dergisi, and was first published in Turkish in September 2016 under the title “Gay Liberation Through Socialist Revolution! A Political History of the Lavender and Red Union’s Gay Communism.”

M: You grew up in the south?

Walt: I grew up in the south, mostly in northern Florida in the era of de jure Jim Crow racial segregation. Being in an officially legally segregated society – schools, public facilities, neighborhoods – and my reaction against it, which was based largely on a religious impulse initially, was what initially propelled my political awakening. However, it was kind of stunted because I was a white kid in a fairly backward small Southern town without any allies or anybody much to learn from even. So I would follow things through the news, like the awakening civil rights movement of the late ’50s and early ’60s. When I began to try to reach out to young black people on the other side of town, I quickly got squelched rather vigorously by the town fathers coming down on my parents and threatening to fire them from their jobs if they didn’t shut up their noisy and traitorous kid. So we worked out a compromise that I would cool it for six months in exchange for leaving home early and going to college in the north, which I thought would be a decisive act of liberation and freedom because I would get away from a small Southern town.

M: And go to someplace where everything was enlightened….

Walt: Where everything was enlightened, non-racist, and kind! Well of course that also led to my political awakening at the next stage. Oh! It’s not just the south! Racism is not simply a southern problem. It just has a different accent up here, and different forms. But my political activity was still within the confines largely of liberalism, but inspired by the Southern black civil rights movement and I was in fact organizing fellow university students from the north to support it, and to travel down south and participate in voter registration, and Freedom Summer, and liberation schools and things like that. And then increasingly also turning to community organizing in poor communities in northern cities. I dropped out of university without finishing. Partly over conflict over feeling impulses towards being gay but not being able to accept that yet, or not having a context, or not knowing anybody else.

M: You weren’t in contact with any gay community?

Walt: No. Now remember this period was pre-Stonewall, we’re talking early-to-middle ’60s. I worked with SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] and a group called the Northern Student Movement in Philadelphia after I dropped out and then moved to Washington D.C., worked for the National Student Association, which was basically a confederation of student governments. Unbeknownst to me until later it turned out to have been substantially secretly funded by the CIA together with thirty or forty other cultural and educational and artistic organizations in the US as a Cold War tactic because of the US government knowing that it wanted to be able to operate in third world and left movements internationally but wouldn’t be able to get any traction if it were doing that in the government’s own name.

M: So the whole story of the Lavender and Red Union goes back to the CIA.

Walt: No, but my own history does! So I ended up accidentally coming across this information and helping to expose it, in 1966, 1967. The government was at first going to deny it, but we had enough inside information that could corroborate it. So I got a call in the middle of the night from the controller of the NSA, the person who oversaw the relationship and the funding from the CIA, and he put this guy on the phone who at least said – and this was at three o’clock in the morning – that he was Richard Helms, head of the CIA, and he told me “Young man, you’ve betrayed your country…”

M: Congratulations!

Walt: “…we have ways to do deal with people, like drafting you and sending you to the front lines of Vietnam.” I did stuff like write up the story and put it in a safe deposit box and write stuff telling my parents that if something happens to me…. But fortunately it became a big enough story with national press, and then they started unraveling all these different other organizations…. So I was an embarrassment but it also gave us some protection. Anyway, not too long after that I left the NSA and moved to – I got married – moved to San Francisco, started an alternative school, was involved in the counterculture. And other ways of, you know, the whole mid-late ’60s stuff that we were going to…

M: So you were kind of generically political. You didn’t have a particular direction.

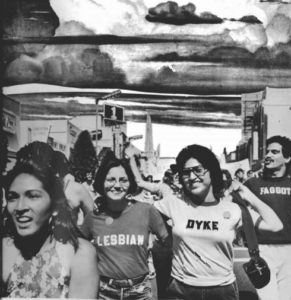

Walt: I knew that I was committed to social justice, to building a new society, but I was not primarily political in any organized way. Then in the course of that I also began to realize that I was queer, and that ultimately my marriage was not going to be sustainable in that context, so I came out, but fairly late, in my late 20s. This was two or three years after Stonewall. Stonewall helped me come out ’cause all of a sudden – OK, here are people that I can identify with, at least the radical wing of gay liberation was something that I could identify with. So I got involved in that a little bit late. Particularly since I moved back to Washington which was a bit late, since Washington D.C. has tended to be politically behind other parts of the country. For example, when I moved back to D.C. in ’72 and the next year ’73, I hooked up with a group of people and we wanted to propose the first gay pride in Washington, and we got shot down violently by the nascent gay community – “Oh no! You’ll turn everybody against us! It will set us back for two years!” – just to have an open gay pride, which was already happening in New York, San Francisco, LA. So Washington was a few years later.

M: Had you been to a gay pride march before then?

Walt: No. I left San Francisco and I came out, and had been dealing with it pretty much on a personal level. So when I got to D.C. I was involved at the gay community level in terms of institution building, like helped to start a counseling center that was peer-based and sort of liberatory-based, not psychologically-based, started an alternative to bars for people that didn’t drink or didn’t like the atmosphere of bars to have social dances and interaction, started a VD clinic which later grew into a health clinic for gay men and ultimately for lesbian women.

M: That’s a lot of things to start. Seems like you were very active.

Walt: Yeah, I was active. I was politically involved with what was left of the Gay Activist Alliance, which had already kind of gone rapidly up and down in DC. We fought things like the discriminatory and racist behavior of the gay bars. They would triple card black gay men in the city, or they would have a quota that when a bar got up to more than 10 or 15 percent black patrons, then they would start discouraging any more coming in on the theory that too many black people would discourage white patrons from coming. So we were fighting racism within the gay community, or within the institutions that serve the gay community. And with the people I was organizing with and with my own experience, looking back over the last few years, we became unhappy with this community building counterculture method of social change, and also with liberal pressure group politics for democratic rights.

M: Why were you unhappy with this? What did you see was limiting yourselves?

Walt: We weren’t getting anywhere. Except short-term and limited demands. And the more you got involved and the more you opened your eyes, you saw that it was an interconnected system of exploitation and oppression, not just a question of a bad policy of the government, or incomplete or imperfect democracy, or not giving enough rights or equality to one group or another. It was a little inchoate but it was largely frustration with a lack of vision. I also personally felt frustrated with the New Left. We were basically informed by the New Left, and one of the things that was typical of the New Left is the old left is bad. They were wrong. That’s associated with the Soviet Union. Nobody wants anything to do with them. At best they’re stodgy, conservative, bureaucratic…. But the part that was frustrating me about this was that we didn’t have anything to learn from the people who came before us. So frustration, or the New Left running its course, led to a number of people who were looking for a chance to study history and a chance to find theory that made sense, that would help explain the world, system, capitalism. At the same time there were beginning to be these generally Maoist pre-party formations, they called themselves – collectives that were aspiring to become part of the new communist movement, towards building a new party.

M: You mean like Revolutionary Union?

Walt: Yeah. Revolutionary Union, October League. Some of them had been around before, like the Progressive Labor Party. The Communist Workers’ Party. And then some of the Trotskyist movement, which had been pretty much off to the side, but present, started coming in and intervening with the New Left in one way or another. So anyways, we found a woman who is now identified as a Maoist, who was a former Communist Party leader who had come down from New York to D.C. in the late ’30s, early ’40s. She agreed to teach the rest of us Marxism. So we collectively studied. We had a study group complex, as we called it, and there were 125 of us in 10 different groups of 12. So I got involved, while continuing the kind of the things that I’ve described before, in studying Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tse Tung Thought – MLM-T3. On the one hand it was very exciting and it was like the first time I had read or study Marxism, other than reading the Communist Manifesto when I was a college freshman. This was like turning on the lights in a tunnel. It was like, Wow! Oh, yeah! OK! Class struggle! Working class! Capital! Fundamental contradiction! Exploitation! Class struggle driving motor force of history! Having that framework, rather belatedly, you know, because I was thirty years old or something coming to this, was exciting. We started having this trouble though, because I brought up homosexuality in the study group complex, and this woman said “No, we can discuss it, but the line’s going to be unless you can show me different, unless you can show me the material basis for homosexuality and it’s theoretical contribution to revolutionary struggle or the working class, you just basically need to know what’s wrong with it. That it’s like bourgeois….”

M: Bourgeois decadence?

Walt: Yeah… a symptom of bourgeois decadence. She wasn’t so overtly homophobic. It was polite and soft in the language, but that was basically the line. It basically was the Chinese Communist Party’s line. That this is one of the many deviations of human behavior that will disappear with socialism. I essentially got marginalized by this MLM-T3 study group complex. They didn’t kick me out because I had some friends who respected me and who would have refused to allow that. But I saw that I was an uncomfortable minority. It made me think back to when I was a twelve year old boy in segregation Florida and there was nobody else there. So I started questioning. These people may have turned on the lights in the tunnel, but they sure do put blinders on. There’s something wrong with this Stalinist-Maoist version of Marxism. And also, I wanted to be queer. A queer communist. A queer Marxist.

M: So through that study group you became Marxist.

Walt: Yes.

M: But you realized, “I am Marxist, but not this Marxism.”

Walt: Yeah. So I started looking around and I found this little ad in a national gay paper that was about two lines at the bottom that said “Gay Liberation through socialist revolution!” I said, “What! Did I read that right? They sound like my kind of people!” So I wrote them from DC. They had just gotten founded about this time, ’74 or early ’75. In between my two years of nursing school, which is what I was doing my last few years in DC, I drove out here to LA to meet them to see what they were like. So I met them and was reasonably impressed, although they were awfully small. There were three to five of them total. I had discussions, and then I went back to DC and I started a little DC gay socialist study group that was using a kind of edited version of that same curriculum of this other study group complex, a little of the Mao and adding in a little Trotsky. Basically it was an introduction to Marxism. I wanted to recruit some other queers to Marxism so that I wouldn’t be the only one. I also tried horizontal recruitment, as they called it – from the straight ones. So that went OK. One person ended up later moving with me to LA to join the L&RU and a couple others remained sympathizers. But I stayed in touch by correspondence with the people out here, the L&RU, and invited them to come to DC. We did a forum for this left milieu called ‘Gay liberation through socialist revolution’. Later through struggle with the Spartacist League we dropped that slogan, but at the time it was cutting edge; it was the main slogan of the L&RU and of course it drove most people in the liberal and sectoralist queer community crazy – “What are you talking about socialist revolution, we just want equal rights”. But we got 125 people to come out to that in DC, including some of the Maoists who spoke up and gave their line, but…. Since I got my nursing degree I came out here to join them.

M: So how did those three or five people in L.A come together?

Walt: I don’t know exactly because I wasn’t here and I don’t remember the stories. I know they were all in the Maoist milieu and so they all had similar kind of rejection experiences to me. Because the Maoist milieu dominated the new left decomposition products of that time, and if you were a radical revolutionary anti-capitalist, that was the main game in town, with the Trotskyists having a little left field pocket, and then the anarchists – I don’t know about LA, but they weren’t a factor in DC. So then in ’76 when I came to LA to join we expanded to 11. So we had brought in more people, including people that were less politically experienced. But there were some core politics, like we believed in a working class orientation, including implantation of cadre in industry and work in trade unions.

M: Can you explain what the implantation of cadre in industry means?

Walt: It’s that you want to recruit people from the working class, but you also wanted to send people who became won to communism into industry or into strategic places where they could help organize other workers or recruit from working class struggles and to work in the trade union movement. So out of our 11 we had two in communications, who were telephone workers and in the communication workers union, and me in health care, joining the health care workers union. We actually talked about that within the L&RU – you notice we weren’t just talking queer politics, we were also trying to do our bit to help build a revolutionary working class movement. That’s a part of the problem that we began to see here pretty soon. First of all, 11 is awful small, being out queer. And so being a gay liberation communist organization was not particularly helpful in organizing a revolutionary caucus within the communication workers union, or the nurses.

M: Did the organization actually send people into these workplaces to organize? You said that was a strategy.

Walt: Yeah. At least one of the communication workers was sent in. The other may have been their to start with, but he was there in part with the idea of being an organizer within. And before we later moved on into the Spartacist League, we were training a couple or three other people for jobs for implantation. Apprenticeships, and skilled trades for example, and electrician, transport workers. We were aiming for somebody in the ports. Didn’t get that far, though.

M: So the goal then in doing this workplace organizing, would not be to, say, organize a queer caucus in the health care workers union.

Walt: No. It wasn’t. Not at that time. And it was also contrary to our politics.

M: Why was that?

Walt: Well, we were saying that the role of queers in the maintenance of American capitalism is not strategic in the same way that black people – and later other people of color – and women is. That American capitalism and the domination of the American ruling class is integrally dependent on maintaining the special oppression of blacks, in particular, and also increasingly Latinos and other immigrant forces, and women. And that gay people are probably not going to find, or likely to find, full democratic rights without the leadership of a radical or revolutionary movement. But it’s conceivable that they could. And I think that in the outcome of the last few years you can kind of see that it’s conceivable that the nominal granting of democratic rights can happen within the structure of capitalism.

So we were saying that we wanted to organize around the things that were strategic and fundamental while we also fought for women’s liberation – and we sort of saw the queer question as in some ways integrally related to that – and for full democratic rights for everybody, that we have to make a point of fighting for everybody, even unpopular or small minorities, whether strategic or not. Though we didn’t organize gay caucuses in our trade union work, we did raise the demand that unions should support full democratic rights and oppose discrimination against LGBT people. That way, we established a track record of the importance of the unions and the working class fighting to defend gay people when under attack, as with all marginalized groups. So we were in a position to quickly mobilize support when pogrom-type attacks came, as later happened during the hysteria around AIDS.

M: Earlier you were talking about whether it was possible to realize full democratic rights under capitalism. I think you were saying that at least for the United States –

Walt: It’s theoretically possible to do that.

M: But it’s not possible to do that for, say, black people, because capitalism, in the US, is formulated on the foundation of racism. But you said that for queer people, it’s more of an… open question?

Walt: Yeah. I would say, once again I personally don’t see it fully, but it’s possible to extend democratic rights more and more and more on things like marriage, on things like serving in the military. They could also do, although they haven’t yet, on nondiscrimination in the workplace, or nondiscrimination in housing. All these are aspects of full democratic rights. They can grant that without threatening hegemony, rule, power, including power to exploit the working class as a whole.

M: In some of Lavender and Red’s writing about their goals or demands for sexuality and for queer struggle, they talked about a vision of being able to actually move beyond gender distinctions entirely, and not have – obviously – straight, gay, bisexual; not have masculine/feminine gender roles, not being assigned male and female. Is that something beyond democratic rights, are those things that you think can be achieved under capitalism?

Walt: No, that’s beyond democratic rights. I think that’s part of what ultimately needs the socialist revolution. But I think that’s integrally related to, and you can contextualize it within, the “woman question”, in the traditional Marxist terminology. In terms of the elimination of patriarchy. I think retrospectively we could have gone beyond this to expand the potential contribution of queerness. But it’s still a terrain that was opened up. I mean we want to be able to, for example, socialize reproduction of labor to create freedom from those traditional sex roles, including forms of sexual partnering. So I would say that’s tied to to the original liberatory vision of Marxism. And we were certainly into extrapolating on that, and talking about that, and envisioning and imagining, but on the other hand we’re not utopians. We’re saying you don’t get these things just by imagining them, you get them by working to change the material bases and the structure of capitalism and class rule.

M: You saw that struggle for liberated gender and sexuality as being part of what you called the “women question”, and also that’s clearly part of the gay liberation struggle. So how did you separate out the gay question from women’s liberation struggles and patriarchy, and separate it as something that was not strategic?

Walt: Well, by saying not strategic doesn’t mean it’s unimportant. But because you were asking me initially around caucuses and about how you would organize caucuses. And it gets back also to sectoralism. To the extent that we sort of made a hard line about this, it was because we were fighting against sectoralism, which we felt is really going to weaken and divert the movement, or building a powerful unified working class movement that can ultimately smash capitalism, and the solidarity necessary to do it. With sectoralism, the tendency is that it ends up focusing more and more on the particular gains and demands and organizing increasingly narrowly around those, and often then it leads to, as we can see time and time again, to bending away from a revolutionary purpose by making alliances and concessions with capitalist forces, particularly liberals, saying “Oh, you support us on this so we won’t challenge your basic power.”

At it’s worst sectoralism can lead to support for fascism. For a very authoritarian form of capitalist state as long as you got your crumbs, or your particular narrow interests were protected. So we were very motivated by fighting against sectoralism. We were talking in terms of how you organize the fight, and particularly when there’s a justification for separate forms of organization. And that wouldn’t necessarily be hard and fast for all time. For us, for a caucus in the health care workers union, or the communication workers union, it was much more important to have a revolutionary or a class struggle trade unionist perspective that we were uniting all people around, as opposed to prioritizing a gay caucus, or a series of caucuses that might be parallel, like a gay caucus, and a women’s caucus, and a Latino caucus, and a this and that caucus. At another time or with a more “advanced” nature of the struggle, you might have some of these different caucuses, all of which were revolutionary and class struggle, and were united at the same time.

M: But going into an industry, the first thing you do would not be going to find the other queer people there.

Walt: Yeah. Right. So, since we’re on the labor thing, I had gotten involved in the trade union struggle activism at Kaiser here in LA as a nurse. I had been involved in the new RN union, including pushing the contract negotiations in the most militant direction I could, including some democratic rights demands, including for queer people, and for the right for Filipinos to speak their language – they had a rule that you couldn’t speak non-English in the hospital even in off-duty areas. And then a strike was coming up from the “non-professional” workers – the vocational nurses, and the nurse’s aides, and the housekeepers, and the dietitians. And so the question was, what are the RNs going to do?, because we were in a different union than the majority of the workers.

The perspective of the union leaders was, “We will keep working. But we will work to rule. We won’t do other workers’ jobs. But we will cross picket lines and come into work to take care of patients because that’s our highest duty and blah blah blah.” I argued as a class struggle trade unionist, no, picket line means don’t cross, working class solidarity is an important principle that we must – in the case of the US – reestablish as inviolate, and furthermore practically for all of you worrying about the patients, if we have a solid strike Kaiser will be much more likely to settle then if we do this piecemeal work-to-rule shit. I was putting this forward as the queer, and also the commie. I put forward a position that no, we need to commit, we need to take a vote to not cross the picket line. I won that argument, and Kaiser settled the strike the next day, without even actually having gone out on strike. That was an example – a small one – of the kind of trade union work and class struggle intervention into a workplace that we tried to do.

M: Is that part of the reason why you thought it was a necessity to go beyond just being a small gay socialist organization, so you could include people like your coworkers? Because you saw it as necessary to organize there, in the hospital, as working class people, and that being working class people was the primary point of unity in the workplace?

Walt: I think so. Plus we needed size and you’ve got to open it up and have it on a different basis if you’re going to recruit size. We weren’t exactly making headway recruiting out of the gay political organizations.

M: Why? Why do you think that was?

Walt: ‘Cause we were commies. I mean ’cause people were saying, “You’re unpopular. I’m a pro-capitalist queer. I want to succeed. I just want the right to make it in this society free from discrimination.” Or they’d say “Oh, my main problem is not as a worker, my struggle is against patriarchy and male bosses.” We were increasingly seeing we were gonna be stuck in a niche that is not exactly a springboard to being part of a movement for power, as long as we were just isolated as a small queer communist organization. That’s just setting aside the question whether we were effective or not in our organizing. But just by definition we were narrowing ourself to this little piece, whereas our basic idea – the more we thought about it, and the more we studied broader history and movements – was that we needed to build a party. That was our belief as people being won to Leninism. That we needed to build a vanguard or a disciplined democratic centralist party. So we needed to find somebody else to hook up with.

M: Did you focus on trying to win the gay community over to socialist politics?

Walt: We tried. But first of all this history is pretty short. We’re talking here just a matter of three, four years maximum before we abandoned that narrow existence. We went to gay pride. We leafleted. We put out a newspaper. We intersected issues in the gay community like the Gay and Lesbian Center strike. We were active in a campaign to boycott some big bar in West Hollywood because of it’s anti-black discriminatory behaviors, just like in Washington. And we would try to organize queer contingents in anti-war and Chilean solidarity demos or actions. We did those kinds of things that would be trying to attract attention. Although then increasingly we focused more on study to try to figure out where to go next. So we took a lot of time reading.

M: What were some of the challenges that Lavender and Red brought to the LA gay movement?

Walt: We basically criticized saying capitalism is the problem, not the solution. Capitalism cannot be reformed. We’re not the only ones in a shaky boat here. That it’s all of us or none. There’s other oppressed groups and if we don’t express and fight for solidarity with your working class fellow gays and lesbians, who are also maybe Latina, and maybe also black, then that even more bluntly poses, well, are you going to have freedom as a black sissy queer without also challenging racism? Without also challenging sex roles and patriarchy? So you put that out there continuously.

M: So pointing out that actually, despite who the leadership of these liberal gay organizations might be, the vast majority of the queer community was in fact the working class, was in fact not white. And so by being so narrowly focused, they were leaving most people behind.

Walt: Yeah. Without fighting the other sources of the oppression of our community.

M: What were some of the challenges that you brought to left organizations around Los Angeles?

Walt: Why are you all so backward? Defending the worst in bourgeois society or Stalinism?

M: Did you have conflicts?

Walt: Well, we had arguments. We would often be shown the door. We would go to meetings that were run by these Maoist organizations or popular front coalitions and speak up, including queer demands or just speaking as out queer communists, and sometimes we’d get thrown out, shown the door by the security squads. You know, they said “You’re being provocateurs”, or sometimes we’d be police-baited, or disunity-baited, or, in a couple cases, “Get out of here faggots – will the security show them the door.” Twice, that I went to.

M: Despite the rejection that Lavender and Red got from the established Maoist left, you still remained very committed to the idea that what queer people needed was socialist revolution.

Walt: Yeah. We thought these weren’t really socialists. They were corrupter socialists, this tradition. Also things were beginning to change. I mean, we were having some impact – not just us, other people. I mean these people were getting a bit embarrassed because they were trying to recruit people too, from a broader perspective, like ex-liberals or still liberals, and they were getting uncomfortable with this. We were also suspicious, though, because then people began to switch, including some of the Trotskyist groups, like not only the SWP [Socialist Workers Party], but Workers’ World. We would point out the hypocrisy of these groups that a few years ago wouldn’t talk about queer people, and now they didn’t come out with some analysis admitting how come they were wrong and why they changed, they just suddenly started being friendly and welcoming and adding a few token gay demands to their kitchen sink demand list. We were telling other gay people, don’t be fooled by this kind of pandering. Ask for their analysis. Where’s their strategy. Where’s their program. And, most fundamentally, do they have a program for overthrowing capitalism.

M: Seeing the class contradiction, seeing the struggle between the working class and the capitalist class as being the crucial linchpin, is that perspective what made Lavender and Red realize it was necessary to not just organize gay people, not just organize working class gay people, but also to be together with anti-racist and feminist, and anti-imperialist struggles?

Walt: Yeah, yeah, yeah, absolutely.

M: You talked about how your perspective on feminism was that it needed to be working class feminism. And you came into some debates about that with feminist groups during the strike at the Gay Community Services Center, which was one of the first established gay social service organizations, and which ended up getting a lot of funding….

Walt: This was actually before I moved out from DC, so I just know this second hand. But the workers attempted to organize a union because there were wholesale and arbitrary firings. And we supported those workers, and to some extent we might have implanted the idea that you need a union, you need to organize and negotiate as workers with the management for wages, working conditions, and against arbitrary firings.

M: One account I was reading basically said that the Lavender and Red Union were the people who came to the workers and said, “You should go on strike”, and that idea won out, but there is one quote from one of the workers who was speaking against Lavender and Red’s proposal, saying “This is not a labor issue. Our fight is about lesbian feminism versus male dominated hierarchy.” It seems Lavender and Red’s position was that actually workers being fired for organizing against their boss is probably a labor issue.

Walt: Yes! I think so. That’s not to deny, and we didn’t at the time, that it’s not also a feminist issue.

M: So how did that play out in that strike?

Walt: As I recall the workers lost, but our position got a substantial amount of respect. But there was some lingering disagreement, sort of like markers were cast down: OK, this is how they see it, this is how we see it. But it did raise the issue – for some people for the first time – that even in the nonprofit, NGO, social services sector, there are labor issues. That because we’re a queer organization does not suddenly resolve capitalism or resolve the tendency of bosses and managers to exploit, and abuse, and mistreat workers. That workers have a right to organize. And I think we had some modest success in at least instilling these basic principles which we were fighting for.

M: How did Lavender and Red see this NGO-ization of the early gay movement affecting things and what was your position on it?

Walt: It hadn’t really happened yet enough for us to take it up as that issue specifically, except in specific concrete cases like this one. We saw that strike as an example of that, that a voluntary organization becomes an institution. We didn’t foresee that it was going to become a tidal wave, or the degree to which it became the dominant mode.

M: Lavender and Red’s existence is very interesting because it was very contradictory in the sense that this group formed that saw there was no place for queer struggle in the revolutionary left, and then at same had a political understanding that there was no place for queer struggle by itself. And so I guess Lavender and Red probably saw its own existence as something of a failure.

Walt: Well, yeah, it certainly was contradictory from the start. That contradiction was embedded in it. But I would say that’s not necessarily a failure, to have then gone through and transformed ourselves, and whoever else we influenced, with a vision that was not only transformative but transitional to a different perspective. And we probably played a small role in helping to transform at least a corner of the left. I would say that we also, we and other people who came along after us or in parallel, did have struggles within the left to clarify, or rectify, or challenge leftover or former positions. And a lot of these contradictions still…. Well, I started to say still exist but….

M: But for the contradictions to exist in the left, the left would need to still exist.

Walt: Yeah, that’s why I sort of backed off. No, the thing that I’m saying that still exists, because I saw it again in Act Up twenty years later, was the fight against – in less explicitly political terms most of the time – a sectoralist, single-issue approach versus any solidarity, integrated struggle, and anti-capitalist perspective. And that has existed in different movements in the queer community as well.

M: So this approach against having a focus on just this one oppressed sector, and instead organizing in the united working class struggle with other oppressed groups – that’s a perspective saying that revolutionary political organizations shouldn’t be based only in one oppressed group. But is it a perspective saying that social movement groups shouldn’t be only based in one community as well?

Walt: I personally wouldn’t say that. I would say that there are rules for mass movements that are based in one sector, but there’s always going to be the danger of that bending towards class collaborationism and accommodation with capitalism unless there’s some countervailing active tendency. So I think, like your Chilean comrade was saying in that meeting a couple weeks ago, there are being different sectors of the popular movement, but then you need to have a party, a political organization, a formation, a structure, by which the unity of the struggles and the cross-fertilization and the critique and challenging takes place within the popular movement sectors. So I would say that I can certainly see – first of all, it’s going to happen whether I or any other revolutionary approves of it – but I can see that it’s not necessarily something to always to be fought and polemicized against, but to maybe be intervened within with a unified revolutionary perspective, and to have some way to link these together. And at times then it may outlive its usefulness. You could actually see if it’s objectively becoming more of an obstacle in it’s sectoral boundaries than it is a benefit in its mass mobilization potential.

M: Tell me a little bit about the transformation of the Lavender and Red Union. You said that after this period of intense activity, there was then a period of intense political study, saying “OK we’ve been doing this work in the left, in the gay community, where are we going?”

Walt: Right. Part of it was since we were coming out of a Maoist milieu, even though we weren’t splitting from any explicit organizational connection, we felt like we needed to decide between the original Bolshevik vision of global international revolution, or as Trotsky concretizes, permanent revolution, versus the Stalinist/Maoist conception of socialism in one country, that, among other things led to accommodations with the…

M: National bourgeoisie.

Walt: National and international bourgeoisie. I mean, this was also Nixon in China time, you know. That shook up a whole lot of people in the Maoist left milieu – “What the fuck is he doing? The butcher of Vietnam being welcomed to Beijing!” That was the first big study. And so we came up with a document rejecting socialism in one country. So then we decided, OK we’re basically committed to the Trotskyist tradition, so, which one?

M: It may seem interesting to someone that a gay communist organization would spend so much time studying the question of socialism in one country instead of spending that time studying sexuality and gender.

Walt: Well we saw ourselves as a part of – or wanted to be a part of – the global communist movement for revolution. And you can’t just study one piece of that. You’ve got to try to find the central dividing lines or questions. That’s the one that we encountered.

M: And it had a lot of importance in the context that you were in at that time.

Walt: Yeah, right now it might seem arcane and esoteric, but I think in the context why we did that instead of sexuality is not so hard to understand, because we were gay communists. Or gay revolutionaries. So he needed to study and sort ourselves out according to the key revolutionary questions that were facing us, as well as then we would expect to dialogue and counter with any putative partners about how they related to queerness and sexuality.

M: Basically at that point you’re just choosing between Stalinism and Maoism and Trotskyism.

Walt: Yeah. This was a two stage process. The first was to choose Trotskyism and then to move to find out what form of Trotskyism. Then that requires a study of the Russian question. Is the Soviet Union a degenerated workers’ state, or is it state capitalist, or bureaucratic collectivist? Once again a question that seems far removed from queer liberation, and I tell you people that we talked to about this said “Are you guys crazy?” Then somebody wrote a little headline on a story about the fusion of the Red Flag Union – as the Lavender and Red Union was known at that time – with the Spartacist League as “The fruits merge with the nuts”.

M: After the Lavender and Red Union began studying the Russian question, there were a number of parties that came trying to….

Walt: Trying to pitch their version to us. We talked to the SWP, we talked maybe briefly to Workers World, although by that time nobody much had much respect for them; they had already gone over to Kim Il Sung as an exemplar of the revolution [then communist leader of North Korea]. Though maybe that came a little later. And the International Socialists [the predecessor to the International Socialist Organization (ISO)], and the RSL [Revolutionary Socialist League], which had been kind of a left split from the IS. We did talk to the Freedom Socialist Party too. They were the ones that were articulating the vision of socialist feminism. But it pretty much came down to between the Spartacist League and the Revolutionary Socialist League. It ended up being a twelve-three split. Twelve of us joined the Sparatacist League and three joined the RSL.

It was partly a question of the way you came down on the Russia question. But it was also partly a question of style, temperament, and bent thing. The RSL was a little more loose, not such hard democratic centralist in their style. Right after the merger we were all in LA, and the Spartacist League was saying “OK, we’re a national and international tendency, so you can’t all stay in LA because we want you to spread out, so where are you going to go?” And some of us went to Detroit. Partly because the auto industry was hiring again. So there was going to be an opportunity of implanting a bunch of people in the auto industry after a period of stagnation and shrinking. As far as I know those three people who went with the RSL stayed in LA. The SL fraction split up – a couple stayed here, some went to Detroit, Boston, Chicago, New York.

M: So the Lavender and Red Union mostly joined the Spartacist League, and the Spartacist League allowed you to filter out across the country. So what happened next? What was the legacy that you saw the Lavender and Red Union having within further organizing and militancy?

Walt: I think that one theme of this discussion is that we felt like we were able to express our deeper or broader political commitments through our involvement in a more comprehensive national and international revolutionary organization. To that extent I think we felt like it was successful for us as individuals and for the continuity of the political work or the political vision that we had. Later the SL certainly got more involved in queer struggle, even during the time that I was still there, which I was there for ten years. Like that case in Chicago. We were explicitly defending and mobilizing and getting labor union locals to defend a gay pride march in Chicago from a Nazi attack. And most of the rest of the left eschewed or shied away from that. The most they would do was say, “Oh, let’s have a rally to protest the horror of the idea of the Nazis.” And we’re saying “Fuck that namby-pamby liberal-ass shit, let’s stop them from coming here.” Lavender and Red Union people had different skills. Some people continued to work in the communication workers’ union, for example, only in a different city. Some people found skills as internal organizers, apparatus people. I worked in both health care and in these anti-fascist mobilizations, and in the legal and political defense work. People went through with apprenticeships and were implanted into industry and industrial fractions. At that level, I would say that we also were able to bring the particular knowledge and skills of the queer community where there were opportunities to intersect, like with the anti-fascist organizing, and later in the AIDS movement, including infusing in the party – before the Spartacist League got totally isolated – and the other forces it it influenced in Europe, and Mexico, South Africa, Poland, Russia, with its commitment to queer liberation, queer rights as a part of a comprehensive communist party. That we brought that, our tradition and our personal histories into the broader life of this broader political organization; I think that had an impact.

M: Do you feel that the Lavender and Red Union was able to spread a bigger change to the rest of the left.

Walt: Yeah.

M: And so then you left after ten years.

Walt: Largely I burned out and just needed to take a few years off. But I was also beginning to question the continued relevance of the Spartacist League’s fairly narrow application of Trotskyism and democratic centralism. Because I feel like the farther you get away from having a history of active involvement in leadership in mass workers’ struggles, the more distorted, precious, esoteric, and just quirky the idea of embodying this tradition becomes. My own politics now, I would say I define myself as an anti-capitalist revolutionary, and sometimes I say I’m a communist. I mean readily I’ll say that, it’s just not always appropriate. But I’m not affiliated with any particular political organization or sectarian tradition. I’m still influenced by the Trotskyist tradition of Marxism more than any other single tradition, but I believe in, and I’m open to, more eclectic revolutionary anti-capitalist movement building. So there’s this organization COiL [Communities Organizing in Liberation] that I’ve been an associate member of, and I’m a member of this Ultra-red political sound art collective that’s international in three countries, and largely involved in trying to build a mass movement of tenants for housing justice, connected to the other struggles against capitalism that people in LA are engaged in right now.

M: You were involved in the AIDS movement after you left the Spartacist League.

Walt: I was. And I went back to school, got graduate degrees, and then AIDS kind of happened. So that’s where I worked. I was involved in Act Up, and more broadly in pushing things within the AIDS movement that came out of that tradition that I’ve been a part of. Which is that an injury to one is an injury to all, that struggles against capitalism, against all forms of oppression, are indivisible. That you’ve got to solve the AIDS crisis with people who are also poor, black, trans, living in under-resourced countries, and that therefore the struggle has to be reflective of, or address, or connected to, struggles against all forms of oppression. And I’ve similarly found myself oppositional in many cases to people who said “No, the emphasis has just got to be on getting resources and focusing the attention of the system to solve this one crisis.”

M: Any concluding wisdom on the lessons of the Lavender and Red Union?

Walt: Talking indirectly to the Turkish comrades, one of the things that we were attracted to from the Lavender and Red Union in the Spartacist League, is that the Spartacist League was committed to internationalism in an active way. Not just solidarity. But trying to found, or bond with, or establish relationships with revolutionary groups in other non-US countries. And that the US left should subordinate itself to an international revolutionary collective process, at least in ideal, and move in practical concrete steps. I still believe that.

If you enjoyed this piece we recommend you read “Queer Liberation is Class Struggle” and “Refusing to Wait: Anarchism and Intersectionality.”