by Felipe Corrêa

This article was originally published in 2010 by the Brazilian journal Espaço Livre. It has subsequently been republished by the Institute for Anarchist Theory and History.

It has been translated by Enrique Guerrero-López (a member of Black Rose/Rosa Negra). It is again republished here in its entirety.

Introduction

The present text aims to discuss, from a theoretical-historical perspective, some organizational issues related to anarchism. It responds to the assertion, constantly repeated, that anarchist ideology or doctrine is essentially spontaneous and contrary to organization. Returning to the debate among anarchists about organization, this article maintains that there are three fundamental positions on the matter: those who are against organization and / or defend informal formations in small groups (anti-organizationism); supporters of organization only at the mass level (syndicalism and communitarianism), and those who point out the need for organization on two levels, the political-ideological and the mass (organizational dualism).

This text delves into the positions of the third current, bringing theoretical elements from Mikhail Bakunin and then presenting a historical case in which the anarchists held, in theory and in practice, that position: the activity of the Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria (FAKB) between the twenties and forties of the twentieth century.

Anarchism: Spontaneity and Anti-Organizationism?

Kolpinsky, in his epilogue to the compilation of texts by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Vladimir I. Lenin on anarchism—a work financed by Moscow in the Soviet context to promote the ideas of Marxism-Leninism—claims that anarchism is a “petty-bourgeois” doctrine, “alien to the proletariat”, based on “adventurism”, on “voluntarist concepts” and in “utopian dreams about absolute freedom of the individual”.1 Besides this, it emphasizes:

“Typical of all anarchist currents are the utopian dreams of the creation of a society without a State and without exploitative classes, through a spontaneous rebellion of the masses and the immediate abolition of the power of the State and of all its institutions, and not through the political struggle of the working class, the socialist revolution and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat.”2

Claims of this kind have been made throughout the history of anarchism, by its adversaries and enemies, and they are still being made, although various recent theoretical and/or historical studies have shown that such claims are not supported by the facts.

Spontaneism3 and the position against organization are not political-ideological principles of anarchism and, therefore, are not common to all its currents. The organizational question constitutes one of the most relevant debates among anarchists and is at the base of the configuration of the currents of anarchism themselves.

A broad analysis of anarchism in historical and geographical terms allows us to affirm that there is a minority sector opposed to organization and a majority sector advocating it. Anarchists have different conceptions of mass organization, including community and union organization, and different positions about the specific anarchist organization.4

Three Anarchist Positions on Organization

1. Anti-organizationism, which is situated, in general, against organization, at the social, or mass level, and the political-ideological level, specifically anarchist, and defends spontaneism or, at most, organization in informal networks and/or small groups of militants.

2. Syndicalism and communitarianism, which believe that the organization of anarchists should be created only at the social, or mass level, and that anarchist political organizations would be redundant, and in some cases even dangerous, since popular movements, endowed with revolutionary power, can carry out all the anarchist propositions.

3. Organizational dualism, which maintains that it is necessary to organize ourselves, at the same time, in mass movements and in political organizations, with a view toward promoting anarchist positions more consistently and effectively within broad based movements.

Anti-organizationism is based on propositions like those of Luigi Galleani, an Italian anarchist militant who believed that a political organization—or, as his countryman Errico Malatesta referred it, an “anarchist party”—necessarily leads to a government-type hierarchy that violates individual freedom:

“The party, any party, has its program, which is its own constitution; has its assembly of sections or delegate groups, its parliament; in its governing body or in its sections executives have their own government. Therefore, it is a gradual superimposition of bodies by means of which a real and true hierarchy is imposed between the various levels and those groups that are linked: to discipline, infractions, to the contradictions that are treated with their corresponding punishments, which can be both censorship and expulsion.”5

Galleani argues that anarchists should associate in loosely organized, almost informal networks, since he believes that organization, especially programmatic, leads to domination, both in the case of anarchist groups and in popular movements in general. For Galleani, “the anarchist movement and the labor movement travel along parallel paths and the geometric constitution of parallel lines is made in such a way that they can never meet or coincide”. Anarchism and the popular movement constitute, for him, different fields; the workers’ organizations are victims of a “blind and partial conservatism” responsible for “establishing an obstacle, often a danger” to anarchist objectives. Anarchists, he maintains, must act through education, propaganda, and violent direct action, without getting involved in organized mass movements.6

Syndicalism and communitarianism are linked to the idea that the popular movement carries all the conditions for including libertarian and revolutionary positions, such that it would fulfill all the necessary functions for a process of transformation; in this sense, anarchist political organizations are unnecessary or a secondary matter. If the defenders of organization exclusively at the community level are scarce (like the proposals of the North American Murray Bookchin), the same is not true for revolutionary syndicalism and anarcho-syndicalism.7

This position is defended by many revolutionary syndicalists, as was the case of the Frenchman Pierre Monatte, who in the Amsterdam Anarchist Congress of 1907 claimed that revolutionary syndicalism “is good enough on its own.” Monatte believed that popular movement initiated by the General Confederation of Labour (CGT) in France in 1895 had made possible a reapproximation between the anarchists and the masses, and therefore recommended “that all anarchists join syndicalism.”8 Beyond the relevance of this reflection in the historical context after the estrangement between anarchism and mass movements that had taken place in France after the Paris Commune, this position of Monatte was predominant in twentieth century anarchism all over the world, if not in theory, at least in practice.

In that same congress, which can be considered the first historical moment of broad debate on organizational issues within anarchism, other anarchists took a position. Malatesta agreed with anarchist participation in the popular movements, but added: “Within the trade unions we must remain anarchists, with all the strength and breadth implicit in that definition”9. That is, anarchism couldn’t be dissolved in the union movement, couldn’t be swallowed by it and cease to exist as an ideology or doctrine with its own positions and organization. A similar position, but with a more emphatically class basis, was upheld by Amédée Dunois, who defended, in addition to union work, the need for an anarchist organization:

“The syndicalist anarchists […] are left to themselves and outside the union they have no real contact with each other or with their other colleagues. They don’t have any support and they don’t get help. Therefore, we intend to create that contact, provide that constant support; and I am personally convinced that the union of our activities can only bring benefits, both in terms of energy and intelligence. And the stronger we are—and we will only be strong by organizing ourselves—the stronger will be the flow of ideas that we will be able to sustain in the labor movement, which will, little by little, be impregnated with the anarchist spirit. […] It would be enough for the anarchist organization to group, around a program of practical and concrete action, all the comrades who accept our principles and who want to work with us, according to our methods.”10

The positions of Malatesta and Dunois refer to organizational dualism, which is based on the idea that anarchists must organize themselves, in parallel, on two levels: one social, mass, and the other political-ideological, anarchist. Malatesta defines the “anarchist party” as “the ensemble of those who are out to help make anarchy a reality and who therefore need to set themselves a target to achieve and a path to follow.” “Staying isolated, with each individual acting or seeking to act on his own without entering into agreement with others, without making preparations, without marshalling the flabby strength of singletons”, means for anarchists “to condemning oneself to impotence, to squandering one’s own energies on trivial, ineffective acts and, very quickly, losing belief in one’s purpose and lapsing into utter inaction”. The way to overcome isolation and lack of coordination is by investing in the formation of an anarchist political organization: “If he does not want to remain inactive and powerless, [the militant anarchist] will have to find other like-minded individuals, and become an initiator of a new organization”.11

However, for him, the specific anarchist organization is not enough: “Favoring popular organizations of all kinds is the logical consequence of our fundamental ideas and should be an integral part of our program”.12 In this sense, he points out the need for intense base building work within mass popular organizations:

“It is therefore necessary, in normal times, to carry out the long and patient work of preparation and popular organization and not fall into the illusion of short-term revolution, feasible by the initiative of a few, without sufficient participation of the masses. In that preparation, taking into account that it can be carried out in an adverse environment, there is, among other things, propaganda, the agitation and organization of the masses, who must never be neglected.”13

Organizationist anarchists (syndicalists, communitarians and organizational dualists) have contributed, theoretically and practically, to the debate on the organizational issues within anarchism. Organizational dualism has made theoretical and practical contributions discussed below, through the writings of Mikhail Bakunin and the experience of the Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria.14

Anarchism and Organizational Dualism: The Writings of Mikhail Bakunin

Organizational dualism is found in the very roots of anarchism and is formulated in the work of Bakunin, who frequently refers to the practices of the Alliance within the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA).15

For Bakunin the Alliance had a dual objective: on the one hand, to strengthen and stimulate the growth of the IWA and, on the other, to unite those who have political-ideological affinities with anarchism around some principles, a program and a common strategy.16 In short, create and strengthen a political organization and a mass movement:

“They [Alliance militants] will form the inspiring and vivifying soul of that immense body that we call the International Workers’ Association […]; then they will deal with issues that are impossible to discuss publicly; they will form the necessary bridge between the propaganda of socialist theories and revolutionary practice.”17

Bakunin argues that the Alliance does not need a very large number of militants: “the number of these individuals should therefore not be huge”; it constitutes a political, public and secret organization, of an active minority, with collective responsibility among the members, which brings together “the most secure members, the most devoted, the smartest and the most energetic, in a word, the most intimate ones”, gathered in several countries, in conditions to decisively influence the masses.18

This organization is based on internal regulation and a strategic program, which establish, respectively, its organic functions, its political-ideological and programmatic-strategic bases, forging a common axis for anarchist action. According to Bakunin, only “those who have frankly accepted the entire program with all its theoretical and practical consequences and that, together with intelligence, energy, honesty and discretion, still have revolutionary passion” can become members of the organization.

Internally, there is no hierarchy between members, decisions are made from the bottom up, generally by the majority (varying from consensus to simple majority, depending on the relevance of the issue), and all members abide by the decisions made collectively. That means applying federalism—understood as a form of social organization that should decentralize power and create “a revolutionary organization from below upward and from the margin to the center”—to the internal bodies of the anarchist organization.19

To encourage the growth and strengthening of the IWA in different countries and influencing it in its program also constitutes, as noted, one of the objectives of the Alliance. This broad international and internationalist mass movement, according to Bakunin “must be the protagonist of the social revolution, since no revolution can succeed if it is not exclusively by the force of the people”.20 Such a revolutionary process—which cannot be limited to essentially political changes, and must reach the deepest social foundations, including the economy—alters the foundations of the capitalist and state system and establishes libertarian socialism.21

“The International Workingmen’s Association, faithful to its principle, would never support a political agitation that does not have as its immediate and direct objective the complete economic emancipation of the worker, that is, the abolition of the bourgeoisie as a class economically separated from the mass of the population, nor any revolution that from the first day, from the first hour, does not include social liquidation on its banner. […] It will give to labor unrest in all countries an essentially economic character, setting as objectives the reduction of the working day and the increase of wages; as means, the association of the working masses and the formation of resistance funds. […] In short, it will expand by organizing itself firmly, crossing the borders of all countries, so that, when the revolution, led by the force of things, has emerged, there will be a real force, knowing what it must do and, for that very reason, able to seize it and give it a truly constructive direction for the people; a serious international organization of workers’ associations of all countries, capable of replacing that political world of the states and the bourgeoisie.”22

The mass movement mobilizes the workers through their economic needs and organizes union struggles in the short term through their own organizational mechanisms and worker-created institutions spanning the workplace and places of residence; the permanent accumulation of the social force of the workers and the radicalization of struggles allows for advancing toward social revolution.

Creating a popular association based on economic needs implies “initially eliminating from the program of this association all political and religious questions”, as the most relevant is “to seek a common basis, a series of simple principles over which all the workers, whatever their political or religious aberrations, […] are and should be in agreement”.23 While the economic question unites workers, political-ideological and religious questions separate; these, although they do not constitute principles of the IWA, must be debated throughout the process of struggle.24

This is about encouraging class unity among the workers, through association around common interests of a group of oppressed subjects—workers from the countryside and the city, peasantry and the marginalized in general—for the direct class struggle against the ruling classes, since “the antagonism that exists between the world of the working class and the bourgeois world” does not allow for “any reconciliation.” In the class struggle the workers know “their true enemies, which are the privileged classes, including the clergy, the bourgeoisie, the nobility and the State”, they understand the reasons that unite them with other oppressed groups, they acquire class consciousness, perceive shared interests and learn about political-philosophical issues; all of this constitutes a true pedagogical process.25

The mass movement must build the organizational and institutional foundations of the future society and maintain coherence with its revolutionary and socialist objectives. Bakunin underlines the indispensable coherence between means and ends and emphasizes that a “free and egalitarian society will not emanate from an authoritarian organization; therefore, the International, the embryo of the future human society, must be, from now on, the faithful image of our principles of freedom and federation, and reject within its bosom all principles tending to authority, to dictatorship”. The IWA, then, must be organized in a libertarian and federalist way. It is necessary “to bring that organization as close as possible to our ideal”, encouraging the creation of an organizational and institutional scaffolding that can replace capitalism and the State: “The future society should not be anything other than the universalization of the organization that the International has created.”26

The Alliance does not exercise a relationship of domination and / or hierarchy on the IWA, but complements it, and vice versa. Together those two organizational bodies complement each other and enhance the revolutionary project of the workers, without the submission of either of the parties.27

“The Alliance is the necessary complement to the International …But the International and the Alliance, tending towards the same end goal, pursue different goals at the same time. One’s mission is to bring together the working masses, the millions of workers, with their different professions and countries, across the borders of all States, in a single huge and compact body; the other, the Alliance, has the mission of giving to the masses a truly revolutionary leadership. The programs of one and the other, without being in any way opposite, are different by the very degree of their respective development. That of the International, if taken seriously, contains in germ, but only in germ, the whole program of the Alliance. The program of the Alliance is the ultimate expression of the [program] of the International.”28

The union of these two organizations—one political, composed of minorities (cadres), and another social, composed of majorities (masses)—and their horizontal and permanent organization enhance the strength of workers and increase the opportunities of the anarchist process of transformation. Within mass movement, political organization makes anarchists more effective in the disputes over positions and redirects forces that are aimed in the opposite direction and that may tend to elevate to the status of principle any of the different political-ideological and/or religious positions; minimize the eminently class character of the movement; strengthen reformist positions (which see reform as an end) and encourage the loss of combativeness; establish internal hierarchies and / or relations of domination; direct the forces of the workers towards elections and/or towards strategies of change that imply the takeover of the State; submit the movement to parties, states or other organizations that eliminate, in this process, the protagonism of the oppressed classes and their institutions.29

Anarchism and Organizational Dualism: The Experience of the Federation of Anarcho-Communists in Bulgaria

Below we present the general lines of anarchist organizational dualism developed by the experience of the Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria (FAKB) between the twenties and forties of the twentieth century.

In Eastern Europe, anarchists played a decisive role in 1903, during the Macedonian Revolt, where they participated in two events of a libertarian nature: first the Ilinden revolt and the proclamation of the Commune of Krouchevo, followed by the Preobrojenié insurrection and the proclamation of the Strandzha Commune. This was responsible for taking over territory, carried out experiences of self-management for a month and was the first local attempt to build a new society based on the principles of libertarian communism. After the crushing of the revolt and the commune, they founded relevant newspapers in Bulgaria such as Free Society, Acracia, Probuda or Rabotnicheska Misl; various anarchist groups also appeared, and in 1914 a group from Ruse laid the foundations for an anarcho-syndicalist movement. After problems caused by World War I, Bulgarian anarchism resurfaced renewed with the founding of the Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria (FAKB), in 1919, at a congress in which 150 delegates attended.

“In the hot year of 1919, at the height of the global worker’s revolt against capitalism, Bulgarian anarcho-syndicalists (the first groups having been established in 1910) and the core of the old Macedonian-Bulgarian Anarchist Federation (a nucleus of which had been founded in 1909) called for the movement to reorganise. The Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria (FAKB) was founded at a congress opened by the anarchist guerrilla Mikhail Gerdzhikov (1877-1947), a founder of the Macedonian Clandestine Revolutionary Committee (MTRK) in 1898 and commander of its Leading Combat Body during the 1903 Macedonian Revolt.”30

In Bulgaria, the FAKB led relevant experiences that involved urban and rural unionism, cooperatives, guerrillas and youth organization: “the FAKB consisted of syndicalist, guerrilla, professional and youth sections which diversified themselves throughout Bulgarian society”. It also helped found and strengthen organizations such as the Bulgarian Federation of Anarchist Students (BONSF); an anarchist federation of artists, writers, intellectuals, doctors and engineers, and the Federation of Anarchist Youth (FAM), which had a presence in cities, towns and all the big schools.31

The fifth congress of the FAKB, in 1923, had 104 delegates and 350 observers from 89 organizations, which demonstrates broad anarchist influence, possibly the majority among the workers of Yambol, Kyustendil, Rodomir, town of Nueva Zagora (Khaskjovo), Kilifaevo and Delebets, in addition to the growing influence in Sofia, Plovdiv, Ruse and other centers. The growth of the FAKB attracted severe persecution from the fascist right, which between 1923 and 1931 killed more than 30,000 workers. In this context, many FAKB militants were assassinated and others had to go into exile; even so, those who remained “formed combat detachments known as ‘cheti’ and became involved in a major effort to coordinate an uprising with the Bulgarian Communist Party (BKP) in 1923”, and also engaged in guerrilla fighting, in 1925, together with the BKP and the Bulgarian Agrarian Union (BZS).32

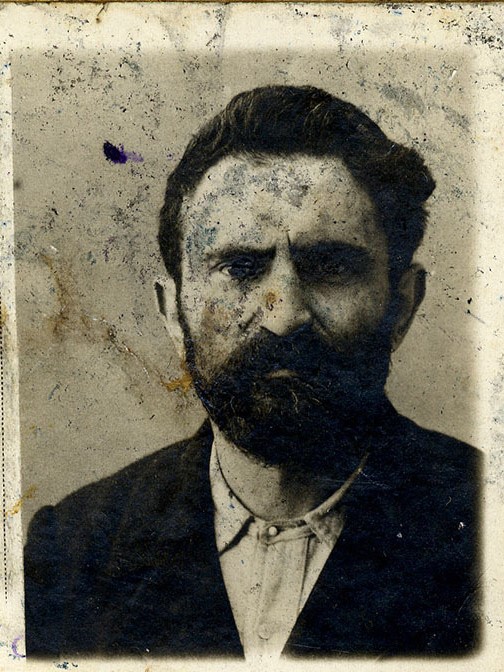

Mikhail Gerdzhikov, anarchist guerilla fighter whose actions helped to found the Federation of Anarcho-Communists Bulgaria (FAKB)

Between 1926 and 1927, the FAKB adopted the proposals of the Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists, a text published in 1926 by the group of Russian exiles who published Dielo Trudá (‘The Workers’ Cause’)33, which called for the need for a programmatic and homogeneous anarchist organization, founded on ideological unity, tactical unity (collective method of action), collective responsibility and federalism. This project had a relevant impact on the development of the FAKB of 1945, the FAKB Platform, which will be addressed later.

In 1930, in Bulgaria, the anarchist influence in the formation of the Vlassovden Confederation, a rural union that was organized around multiple demands: “the reduction of direct and indirect taxation, the breaking-up of agrarian cartels, free medical care for peasants, insurance and pensions for agricultural workers, and community autonomy”. The so-called “Vlassovden syndicalism” spread rapidly—one year after its creation the Confederation already had 130 branches—and accounted for a “huge upsurge of anarchist organising and publishing so that the anarchist movement could be counted as the third largest force on the left, after the BZS then the BKP.”34

During the Spanish Revolution (1936-1939), thirty Bulgarian anarchists fought as volunteers in the anarchist militias.

Between 1941 and 1944, an anarchist guerrilla group fought fascism and allied with the Patriotic Front in organizing the insurrection of September 1944 against the Nazi occupation. Meanwhile, with the Red Army replacing the Germans as an occupying force, an alliance was established between the right and the left — called the “red-orange-brown alliance”—who brutally repressed the anarchists.35 The workers were forced to join a single union, linked to the state, in a policy clearly inspired by Mussolini, and in 1945, at a FAKB congress in Sofia, the communist militia arrested the ninety delegates present, which did not prevent the FAKB newspaper, Rabotnicheska Misl, from reaching a circulation of sixty thousand copies per issue that year. At the end of the 1940s, “hundreds had been executed and about 1,000 FAKB members sent to concentration camps where the torture, ill treatment and starvation of veteran (but non-communist) anti-fascists […] was almost routine”. Thus ended the experience of the FAKB, which began in 1919.36

Taking stock of this organizational experience, we can conclude:

“Several types of working class organisation were indispensable and intertwined without subordination: anarchist communist ideological organisations; worker syndicates; agricultural worker syndicates; co-operatives; and cultural and special-interest organisations, for instance for youth and women.”37

The practice of the FAKB during those more than two decades, as well as the theoretical reflections that occurred in that period, together with the influence of the Dielo Trudá Platform, were reflected, in 1945, in a programmatic document: the Platform of the Federation of Anarcho-Communists of Bulgaria. According to this document, the FAKB envisaged, basing itself on organizational dualism, an anarchist political organization and a mass movement in the city and in the countryside, made up of unions and cooperatives.

“The anarchist political organization brings together anarchists around anarcho-communist political-ideological principles, is organized regionally and has the following fundamental tasks: to develop, realize and spread anarchist communist ideas; to study all the vital present-day questions affecting the daily lives of the working masses and the problems of the social reconstruction; the multifaceted struggle for the defence of our social ideal and the cause of working people; to participate in the creation of groups of workers on the level of production, profession, exchange and consumption, culture and education, and all other organizations that can be useful in the preparation for the social reconstruction; armed participation in every revolutionary insurrection; the preparation for and organization of these events; the use of every means which can bring on the social revolution.”38

Anarchists also participate in mass movements, especially in unions and cooperatives. Unions must organize the force of workers by workplace or job category, and must be based on federalism, direct action and class autonomy and independence. Their core tasks are:

“The defence of the immediate interests of the working class; the struggle to improve the work conditions of the workers; the study of the problems of production; the control of production, and the ideological, technical and organizational preparation of a radical social reconstruction, in which they will have to ensure the continuation of industrial output.”39

Agricultural cooperatives link the landless peasantry and small owners who do not exploit the work of others, and assume the following tasks:

“To defend the interests of the landless peasants, those with little land and those with small parcels of land; to organize agricultural production groups, to study the problems of agricultural production; to prepare for the future social reconstruction, in which they will be the pioneers of the re-organization and the agricultural production, with the aim of ensuring the subsistence of the entire population.”40

Ultimately, the experience of the FAKB, which is reflected in this programmatic document— Platform of the Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria—presents relevant historical elements for understanding anarchist organizational dualism.

Concluding Notes

The relevance of the discussion on organizational issues within anarchism is twofold. On the one hand, it is still necessary to approach anarchism seriously, countering arguments held by its adversaries and enemies, with the intention of providing a more substantial knowledge of that ideology and political doctrine and of its main debates. On the other hand, deepening the discussion on organizational dualism can contribute to the contemporary debate on the organization of the oppressed classes41, providing elements for reflection for those who are interested in resistance movements and the struggle against domination in general, and against capitalism and the state in particular.

Felipe Corrêa is a teacher and political militant in São Paulo, Brazil. He is a participant with the Institute for Anarchist Theory and History (IATH) and Coordenação Anarquista Brasileira (CAB) [Brazilian Anarchist Coordination].

He is also a visiting professor in the School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities at the University of São Paulo (EACH-USP). He researches anarchism, Marxism, socialism, social movements, popular struggles, and the labor movement.

If you enjoyed this article, we would also recommend: Create a Strong People: Discussions on Popular Power and Anarchist Theory and History in Global Perspective.

Notes

1 Kolpinsky, “Epílogo”, pp. 332-333.

2 Ibid., p. 332, italics added.

3 Spontaneism is the notion that the masses mobilize by themselves, without the need for prior organization, formation or preparation, thus being able to carry out large-scale transformation processes. It differs, therefore, from the notion of spontaneity, an inevitable component of any transformative popular movement.

4 For some studies with a transnational or global perspective that contest these claims by adversaries and enemies of anarchism and collaborate with the debate on majorities and minorities in anarchism, see: Felipe Corrêa – Bandeira negra: rediscutindo o anarquismo; Surgimento e breve perspectiva histórica do anarquismo, 1868-2012; “Dossier Contemporary Anarchism: anarchism and syndicalism in the whole world, 1990-2019”; Lucien Van der Walt – “Revolução mundial: para um balanço dos impactos, da organização popular, das lutas e da teoria anarquista e sindicalista em todo o mundo”; Black flame […]; “Global anarchism and syndicalism: theory, history, resistance”; (Editor with Steven Hirsch) Anarchism and syndicalism in the colonial and postcolonial world, 1870- 1940); Geoffroy de Laforcade – (Editor with Kirwin Shaffer) In Defiance of Bouderies: anarchism in Latin American history; Rafael Viana da Silva – “Os revolucionários ineficazes de Hobsbawm: reflexões críticas de sua abordagem do anarquismo”. As these studies and others point out, popular movements based on the workplace and place of residence have constituted social vectors of anarchism throughout its one hundred and fifty years of history, composed on a class-based, combative, independent, self-managed and revolutionary bases. Those movements strengthened anarchist social intervention.

5 Luigi Galleani, The principal of organization to the light of anarchism, p. 2.

6 Ibid., pp. 3, 6.

7 Based on the transnational and global studies mentioned above (Corrêa, Van der Walt, De Laforcade, Viana da Silva), it is possible to affirm that anti-organizationist positions have historically had a significant echo among anarchists, but they were always a minority compared to organizationist positions. The former frequently incorporated individualistic arguments external to anarchism, by authors such as Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche. During the twentieth century, syndicalism was the hegemonic strategic position of anarchism at a global level.

8 Pierre Monatte, “Em defesa do sindicalismo”, pp. 206-207.

9 Errico Malatesta, “Sindicalismo: a crítica de um anarquista”, p. 208.

10 Amédée Dunois, “Anarquismo e organização”.

11 Errico Malatesta, “A organização II”, pp. 55, 56, 60.

12 Errico Malatesta, “A organização das massas operárias contra o Governo e os patrões”.

13 Errico Malatesta, Ideología anarquista, p. 31.

14 Also based on the studies mentioned above (Corrêa, Van der Walt, De Laforcade, Viana da Silva), it is possible to assert that organizational dualism was historically a minority position compared to syndicalism, at least in practice.

15 In those years the general lines of Bakunin’s theory of anarchist organizational dualism were elaborated. The theory of the anarchist political organization was developed by Bakunin, in writings and letters, beginning in 1868, when the Alliance was formed; the writings on the subject elaborated above are not yet fully anarchist and therefore are not used here.

16 Mikhail Bakunin, “Letter to Morago (May 21st, 1872)”. The greatest concrete historical achievement of the Alliance was the creation of sections of the International in countries where it did not yet exist and its impetus where it was already in operation. Such were the cases of Spain, Italy, Portugal and Switzerland, beyond cases in Latin America, stimulated by correspondence.

17 Mikhail Bakunin, “Letter to Cerretti (March 13-27, 1872)”.

18 Mikhail Bakunin, “Letter to Cerretti (March 13-27, 1872)”, “Letter to Morago (May 21st, 1872)”, “Statuts secrets de l’Alliance: Programme et objet de l’organisation révolutionnaire des Frères internationaux”.

19 Mikhail Bakunin, “Statuts secrets de l’Alliance: Programme et objet de l’organisation révolutionnaire des Frères internationaux”; “Statuts secrets de l’Alliance: Programme de la Société de la Révolution Internationale”.

20 A política da Internacional, p. 67. Mikhail Bakunin.

21 Among anarchists it is generally believed that the social foundations of this revolutionary transformation consist in the substitution of systemic domination—especially class domination—by a system of generalized self-management in all three spheres (economic, political and cultural) and a classless society. Through a revolutionary process, anarchists propose to replace: capitalist economic exploitation by the socialization of property, the political domination of the State by democratic self-government, the ideological and cultural domination of religion, education and, more recently, of the media, for a self-managed culture. It is, therefore, a critique of domination in general, with an emphasis on class domination, and a commitment to generalized self-management. See Felipe Corrêa, Bandeira negra: rediscutindo o anarquismo.

22 Mikhail Bakunin, A política da Internacional, pp. 67-69.

23 Ibid., pp. 42-43.

24 This position does not imply a defense of “apoliticism”, but a conception according to which mass movements should not be subordinated or linked to a certain political-doctrinal position. Thus a revolutionary “Anarchist” union—as in the anarcho-syndicalist model, for example— tends to alienate workers who have other beliefs or ideas. It is about taking into account that movements should encompass the different political-doctrinal positions and that a political position cannot subordinate popular movements. Bakunin and the revolutionary syndicalists, anarchists or not, believe that popular movements should organize around concrete flags that unite workers, without a programmatic link to political or religious doctrine. On the other hand, debates between different political positions should take place within movements, although without aiming at the creation, for example, of communist or catholic trade unions, etc. Within a union there should be all workers willing to fight, regardless of their political positions or religious beliefs. (Felipe Corrêa, “Anarquismo e sindicalismo revolucionário”).

25 Mikhail Bakunin, A política da Internacional, pp. 54-56.

26 Mikhail Bakunin, “Aux compagnons de la Fédération des sections internationales du Jura”.

27 Bakunin’s proposal for political organization implies a model—drawing on the classic discussion about “party models”—of a “cadre party” that does not compete in elections and that has popular movements as its field of action; prioritize quality and not the number of members and has rigorous selection and admission criteria, unlike the “mass parties”, which prioritize quantity and whose criteria for participation are very broad, so that, in general, whoever can join.

28 Mikhail Bakunin, “Letter to Morago (May 21st, 1872)”.

29 Two fundamental differences can be pointed out between Bakunin’s organizational theory and that developed by Lenin years later. The first, in relation to internal organization. While the Bakuninist party is federalist and decisions are taken collectively, from the bottom up, in a democratic and self-managed way, the Leninist party adopts democratic centralism: the bases are consulted but decisions are made by the leadership, from the top down, from the hierarchical dome to the bases, which they are obliged to abide by. The second fundamental difference lies in the relationship between the party and mass movements. The Bakuninist party defends a complementary action between party and movements, without any kind of hierarchy or domination exercised by the party, whose function is to strengthen the leadership of these movements, since it is believed that the masses should be responsible for the revolutionary social transformation; the Leninist party, on the other hand, establishes a hierarchy between party and movement and stands above the people, over which it exercises a relationship of domination. While for the former the agent of revolutionary transformation is the mass movement, for the latter these movements are only capable of short-term struggles and the party must endow them with long-term capacity and lead the transformation itself.

30 Jack Grancharoff, Anarquismo búlgaro em armas: a linha de massas anarco-comunista, p. 7.

31 Ibid., p. 9.

32 Ibid., p. 16.

33 Dielo Trudá, “Plataforma Organizacional dos Comunistas Libertários”, 1926.

34 Jack Grancharoff, Anarquismo búlgaro em armas: a linha de massas anarco-comunista, pp. 23-25.

35 Ibid., p. 33.

36 Ibid., p. 36.

37 Ibid., p. 42.

38 Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria (FAKB), “Plataforma da Federação dos Anarco-comunistas da Bulgária”, pp. 61-62.

39 Ibid., pp. 63-64.

40 Ibid., pp. 64-65.