As working class and left movements the world over celebrate May 1st, International Workers Day, we offer our reflection on the current state of the U.S. labor movement – both our optimism around recent strikes and stressing the need to transform the labor movement towards its revolutionary potential. This document was produced by the Labor Sector Committee of Black Rose/Rosa Negra which works to coordinate collective strategy within labor struggles. Also, please consider donating to our Grow Our Roots: 2019 International Solidarity and Social Media Fundraiser.

After decades of decline, workers’ struggle in the U.S. is beginning to show signs of life. Last year marked a potential turning point in the labor movement, reflected in a series of major work stoppages in the education and hospitality industries, along with thousands of nurses, food service workers, and incarcerated workers disrupting business as usual, winning major victories and dramatically altering the terrain of class struggle by reclaiming the strike as labor’s most potent weapon.

As workers take to the streets all over the globe in honor of May Day, or International Workers’ Day, we take a look at the state of the labor movement from a libertarian socialist perspective and set the stage for addressing how we as workers can expand the revolutionary potential of working class struggle in the current moment.

The State of the US Labor Movement

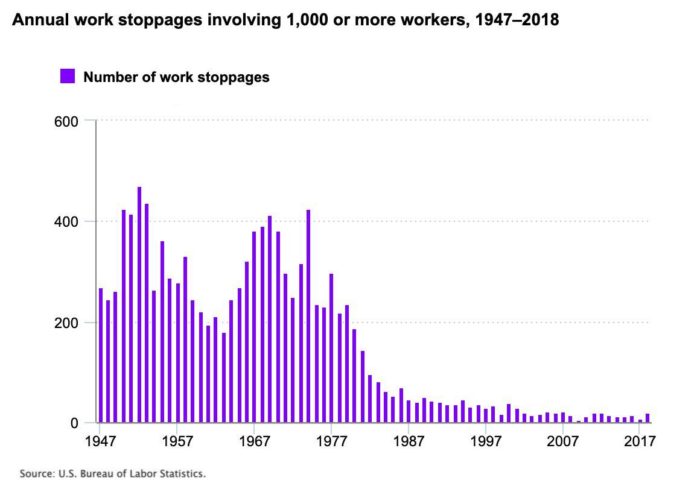

U.S. labor unions have been on the wane for decades. From its peak in 1954 at 34.8 percent, union membership has taken a steep dive to a mere 10.5 percent of the workforce as of 2018. The private sector has experienced the most significant downturn in membership, reaching a staggering low point last year of 6.4 percent— the lowest since 1900. In 1952, the number of work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers reached a record high in the postwar period of 470, with more than 2,760,000 workers striking. Since 1990, however, the number of work stoppages involving more than 1,000 workers has consistently remained below 50, with only seven recorded in 2017.

Since the late ‘60s and ‘70s— the last period of large-scale labor unrest— efforts to reverse labor’s long-term slump have been few and far between. Union leaders have emphasized technocratic solutions, including labor law reform like the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), corporate campaigns driven by paid staffers, and the vain hope that electing more sympathetic Democrats will help pave the way toward rebuilding worker power. While periodic resistance from rank-and-file workers has shown hints of hope, labor has experienced more losses than gains over the years.

The consequences of labor’s decades-long downturn have been devastating. In the absence of a meaningful counterweight in the balance of class power, capital has waged an unrelenting assault on labor. Wages have been stagnant for U.S. workers since the 1970s, social and economic inequalities have grown dramatically, average household debt is on the rise, and capital continues to pass more of the cost of healthcare onto workers, with Black and brown workers hit the hardest.

Amid grim prospects for union renewal, 2018 breathed new life into workplace struggles with 485,000 workers taking part in twenty major work stoppages. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), “the number of major work stoppages […] was the highest since 2007,” and “the number of workers involved […] was the highest since 1986.” Beginning early in the year with a historic wildcat strike in West Virginia, educators in red states across the country went on strike. These educators won major victories and injected a needed burst of energy into a moribund labor movement. While educators and healthcare workers accounted for the bulk of major work stoppages, they were joined by both hotel and telecom workers. In fact, 6,000 Marriott workers in four different states launched the largest hotel strike in U.S. history. This uptick in large-scale strike activity highlights the possibility for expanding workplace militancy in the current moment.

“Simply increasing union density and the number of strikes alone will not address the deep-seated problems we face as workers. We need to understand not only what it will take to grow the existing labor movement, but also what it will take to transform it into a revolutionary social movement.”

Alongside the major work stoppages, a number of important smaller-scale strikes also took place last year. Members of the Industrial Workers of World (IWW), which has played a critical role in organizing food service workers, organized a strike across four Burgerville restaurants in Portland, Oregon, which later became the only fast-food chain in the country to gain federal union recognition. The IWW also played a part in supporting and organizing the nationwide prison strike in August through its Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee. At the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, graduate student workers with the Graduate Employees Organization (GEO) led a nearly two-week-long strike for higher salaries and guaranteed tuition waivers.

Last year’s upsurge has continued unabated into 2019. Beginning with an inspiring week-long strike in Los Angeles, educators in Oakland, Denver, Sacramento City, and North Carolina have carried on the struggle in public education against privatization and austerity budgets that are still lingering since the 2008 crisis. In January, 1,800 non-union, largely undocumented farm workers in Bakersfield, California walked off the job in protest of wage cuts, citing inspiration from the wave of educators strikes. Facing an unprecedented government shutdown, airport workers coordinated a sickout and Sara Nelson, president of the Association of Flight Attendants, threatened a general strike, direct actions that together put an end to the shutdown as opposed to toothless efforts by liberal reformers playing by the rules. Workers in the digital media industry have organized a series of successful union drives in newsrooms big and small, including Vice, Salon, and The Intercept, to name a few. Just two months ago, a second burger chain in Portland, Little Big Burger, joined the Burgerville Workers Union as the second fast food union to exist in the U.S. In New England, more than 30,000 members of the United Food & Commercial Workers struck at 240 Stop & Shop stores over pension and health benefits, costing the company $100 million in lost profit.

Working class women have been at the forefront of the current strike surge, pointing toward growing possibilities for revitalizing a working class feminism. From education to hospitality, the industries at the center of today’s workplace struggles are those associated with social reproduction, where women make up the overwhelming majority of the workforce. Strike victories have reflected the leadership of female workers, with gains in better wages coupled with protections against sexual harassment and assault, breaks for nursing mothers, and parental leave.

Women make up a large percentage of union membership, particularly in the public sector, and have been central to reviving the strike as a tactic both inside and outside the workplace, as in the recent International Women’s Strike.

This ongoing series of strikes stems from changes in the economy, along with increased political mobilization and polarization across the country. Growth in the service sector of the economy and record low unemployment have been accompanied by lean production methods designed to produce more with less, placing increasing strain on workers already struggling with stagnant real wages. Teachers specifically have seen their inflation-adjusted wages fall by 4.5% over the past decade as classroom sizes have grown. At the same time, since Trump’s election millions of people have gained the experience of collective action through joining street protests. A survey at the beginning of 2018 showed that 20% of Americans had protested or been in a political rally since 2016. Half of those who went out for their first protest went to support women’s rights. Protest activity and political consciousness has filtered into the workplace as growing segments of the population are drawn to radical politics in general and socialism in particular.

As the popularity of socialism has risen, so too has public approval for unions. A Gallup poll last year found that 62 percent of Americans approve of unions, the highest number in fifteen years, while another national poll found 50 percent of Americans want to join a union— the highest level in 40 years. This growing support for unions also skews young, with the strongest support found consistently among 18- to 34-year-olds, many of whom are pulling for a specifically “militant labor movement rooted in a multi-racial working class.”

U.S. workers in general, and union members in particular, have become increasingly diverse over the years. Estimates project that people of color will become the majority of the working class by 2032. Workers of color make up a large proportion of low-wage, labor-intensive jobs like food and retail service, commercial and residential cleaning, construction, and “care work” such as home health care and nursing. More than a third of all union members are people of color, and Black workers continue to hold a higher union membership rate than the rest of the working class.

With this uptick in high-profile strikes and increasing support for unionization, we are cautiously optimistic about the possibility for increases in both union membership and rank-and-file workplace actions in the coming years.

These are promising developments, but even if the labor movement succeeds in dragging itself back from the dead, simply increasing union density and the number of strikes alone will not address the deep-seated problems we face as workers. We see worker-controlled, militant unions as a key tool for revolutionary transformation and the creation of a libertarian socialist society. So we need to understand not only what it will take to grow the existing labor movement, but also what it will take to transform it into a revolutionary social movement.

Beyond Unions, But Not Without Them

One of the more significant hurdles to expanding the revolutionary potential of unions in the current moment lies baked into the structure of unions themselves. A bureaucratic, service-oriented form of unionism remains the dominant model in the U.S., controlled by a hierarchy of career officials who operate outside the workplace, manage the sale of labor to capital, confine union struggles to narrow and legalistic “bread and butter” issues within their respective industries, and encourage members to pin their hopes to the Democratic Party.

Despite decades of dashed hopes under Democratic administrations, from Bill Clinton signing NAFTA in the ‘90s to Obama abandoning EFCA, some union leaders are already laying the groundwork for pouring resources into the 2020 elections. While there is a broad-based commitment within unions to oust Trump, many appear to be hedging their bets among a crowded field of presidential hopefuls, waiting for the options to thin out before tossing pennies into the Democratic Party wishing well.

Labor’s unwavering commitment to electoral politics will likely serve to demobilize and defang the current turn toward direct action among many rank-and-file workers, channelling labor discontent into the pacifying arms of electoralism.

Beyond their deep ties to electoral politics, the structural position of the labor bureaucracy also tends to pit union officials against worker militancy. Union leaders often seek to avoid legal and financial risks to the organization or the potential to compromise their relationships with politicians. This was evident in West Virginia, where rank-and-file educators had to bypass attempts by union leadership to call an early end to the strike in favor of negotiation with state officials.

Yet replacing the existing labor bureaucracy with a more radical slate of leaders, or eliminating union bureaucracies altogether, will not be the linchpin that unleashes the latent militancy of workers, who remain largely unorganized, lacking in confidence, and alienated from current unions. Our focus at the moment should be on developing the independent organization and militancy needed for workers to be able to win on their own through the long-haul work of one-on-one meetings, committee-building, and direct action.

The geographic and industrial unevenness of union density represents both the declining strength and influence of unions and a potential opportunity to “organize the unorganized.” According to the BLS, more than half of all union members live in just seven states, located primarily in the Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast. New York and California are home to the largest number of union members, with 1.9 million and 2.4 million members, respectively. Meanwhile, the South remains woefully unorganized. Both North Carolina and South Carolina had the lowest membership rate in 2018, each at 2.7 percent. This leaves a broad field of potential struggle open to more independent, militant forms of worker organization inside and outside of existing unions, especially in the South among Black and brown workers.

As mentioned above, U.S. workers and unions are more diverse than ever, but demographics don’t determine destiny. A “militant labor movement rooted in a multi-racial working class” will not emerge spontaneously from changes in the hue of the workforce. The legacy of white supremacy and its relationship to capital accumulation and competition in the labor market have produced and reproduced systemic racialized inequalities within the working class.

While Black workers are more likely to be union members than any other segment of the working class, particularly in the public sector, they continue to be disproportionately subjected to state violence by police, overrepresented in U.S. prisons, and face nearly double the unemployment rate of white workers. The average wages of Black workers also continue to lag behind the rest of the workforce.

Uprooting entrenched racialized hierarchies within the working class will require unions to take up the totality of issues that affect us as workers in and outside the workplace. This can be seen in the “Black Lives Matter at Schools” campaigns, Labor for Standing Rock, Burgerville workers walking off the job to defend their right to wear “No One is Illegal” buttons at work, and Twin Cities UPS package handlers refusing to ship boxes destined for local police departments in the wake of the Ferguson Uprising.

An anti-racist labor movement will also require a strong defense against attacks on public sector unions in particular. Given its share of union membership and its disproportionately Black and female workforce, the public sector has been subjected to a years-long sustained assault by well-financed right-wing forces, culminating in the recent Supreme Court decision in the case of Janus vs AFSCME. The ruling in this landmark case, which prohibits public sector unions from collecting “agency fees” from nonmembers who benefit from contract negotiations, sparked ominous predictions about labor’s future. Some of the largest unions in the country cut their budgets in anticipation.

While it’s still early to tell what kind of impact the Janus decision will have, the current size and strength of public sector unions are a byproduct of the last round of labor unrest in the ‘60s and ‘70s, not of a favorable legal environment or the ability to collect dues from a largely passive membership. In other words, the best defense against attacks on the public sector will be a militant, offensive struggle. If Janus provokes unions to take this approach— and some have— then it will prove to be an opportunity rather than a challenge.

Legal restraints abound on workplace organizing, from state-level anti-strike laws in the public sector to the Taft-Hartley Act at the federal level. But if there’s a lesson to be learned from recent strikes in education, many of which have flouted state law, it’s that massive, disruptive direct action can overcome many of these barriers.

Despite their clear limitations and contradictions, we can’t ignore or casually dismiss struggles within bureaucratic unions. These unions exist in a number of strategic industries, continue to play a key role as vehicles for workplace struggles and solidarity, and represent the largest mass organizations of workers in the country. Therefore, we must organize within bureaucratic unions, but our task is not simply to build union membership or elect new leadership. We need to build independent forms of worker organization both inside and outside of existing bureaucratic unions, like West Virginia United, a caucus of rank-and-file educators that formed in the wake of the wildcat strike.

Outside traditional trade unions, the IWW has carved out a small but growing pole of attraction within the broader labor movement as the only meaningful organizational expression of revolutionary syndicalism in the country. Beyond their local organizing campaigns in food service and with the National Prison Strike, the IWW has also been on the front lines of the fight against the rise in fascist organizations across the country through its General Defense Committee, and recently affiliated with the new International Confederation of Labor. While the Wobblies have experienced steady growth in membership since the Great Recession, they also have many obstacles to overcome, including an overwhelmingly white, male membership, uneven workplace organizing, a general lack of shared strategic vision, and an overall activist orientation.

Many labor analysts have pointed to so-called “alt-labor” formations, particularly worker centers, as the future lifeblood of the labor movement. Rather than the member-driven, democratic alternative to mainstream unions envisioned by their supporters, worker centers have largely taken the form of “bureaucratic union lite,” mirroring the hierarchical structures and political orientation of their union counterparts, only with fewer members and resources.

To develop the revolutionary potential of the labor movement, we must go beyond unions, but not without them. As workers across the country reclaim the strike, we need to tap into the opportunities of the current moment and expand workplace militancy through rank and file, worker-controlled organizations independent of union bureaucracies and political parties. Whether we work in unionized workplaces or not, we need an alternative to bureaucratic unionism that is rooted in direct democracy, direct action, and worker solidarity across industries and national borders. We need to develop the confidence, skills, and capacity for self-management among all workers— not only to fight for better working conditions, but to challenge capitalism, the state, and all forms of domination toward a free, libertarian socialist society.

In part two of this article series, we’ll elaborate on how we think we can do that by engaging with the current strategic debates on how to renew our unions and organize our workplaces.

If you enjoyed this piece we recommend reading a previous May Day statement from the BRRN Labor Sector Committee “The Next 100 Days: May Day and Worker Resistance Under Trump.”