By Brendan Maslauskas Dunn

This world is engulfed in a whirlwind of myths. But myths give meaning. Every fourth of July I reflect on the power that myths hold over people and how those people above, those that hold all the power, wield those myths and forge them into cudgels, and weapons to be used to keep all of us subservient. To create feelings of doubt when you veer off the path they created. Those myths, especially those creation myths of how the US became a nation started at a young age.

The story was simple when I was young. It’s one that so many of us in the US have been told over the years. The patriots were revolutionaries that were fighting for ideals of liberty, justice and freedom and the British were merciless, blood thirsty colonizers. It makes sense that this creation story is a retelling of David and Goliath. David, as expected, wins. And, even with all of its flaws, the US as a nation, an ideal, was imbued with the notion of progress.

The myth worked for me. I believed in it. I believed in it to such an extent that at the age of thirteen I sent a letter to the Marine Corps requesting to enlist. I was disappointed to learn from the response that I was too young to join but I was given a gift of dog tags that I happily wore, and a promise that the minute I was old enough, a recruitment officer would sign me up.

I held onto that myth of American exceptionalism tightly, but I eventually began to lose my grip and it slowly slipped through my fingers. It was not a rapid change, but one that worked its way into my psyche, little by little over the years.

I was born in the impoverished rustbelt city of Utica, NY. Like all cities, towns and regions in this nation, the national creation myth is repackaged locally. I started to question that local narrative a little more deeply when I was younger, then the national one. In the Mohawk Valley, where I grew up, the heroism of local patriots was lauded. A central figure in the local struggle for independence was militia leader Nicholas Herkimer who died from mortal wounds from the Battle of Oriskany. Another was Reverend Samuel Kirkland, the kind missionary who was a close friend of the Oneida people. Yet another was Peter Gansevoort, the brave commander who repelled the British in their siege of Fort Stanwix – a battle where it is rumored the stars and stripes were first flown. The list of heroic men, with their displays of bravery, honor, and selflessness, is long.

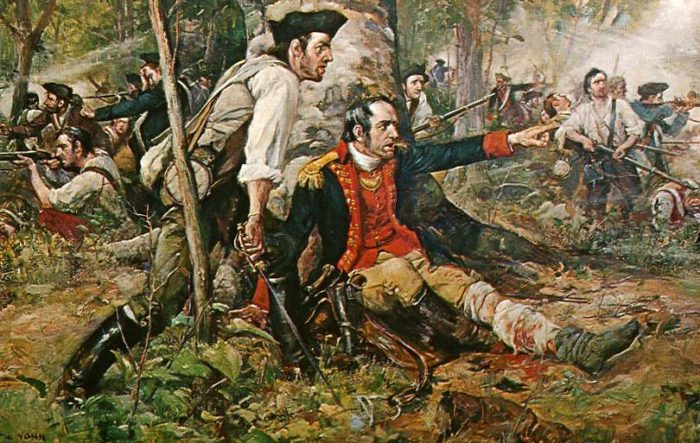

Unsurprisingly, the foes of these great patriots were the British, their loyalist allies, and the Mohawk and other Iroquois warriors who fought with them. They were ruthless, we were told, and wracked a campaign of terror in the Mohawk Valley where they burned down countless patriot villages and massacred civilians. Goliath had reared his ugly head, and only David could slay him.

I remember the day that my high school American History teacher, Mr. Gressler, passed out photocopies of chapters from Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States as assigned reading for my class. Zinn’s argument that the “American Revolution” wavered between “a kind of revolution” rife with contradictions and a revolt of political elites, many of them slave owners and land owners, to consolidate their power resonated with me. In any given area that was gripped by the war, the poorer people tended to side with whichever group had fewer elites. Zinn gave me a chisel to start chipping away at that national creation myth. I used it to reveal the truth that was buried in the Mohawk Valley.

Herkimer, as it turns out, was a slave owner and one of the wealthiest land owners in the Mohawk Valley. Gansevoort was part of the Dutch aristocracy near Albany who for years had amassed a wealth from different business ventures, land speculation and, you guessed it, slave labor. Samuel Kirkland helped create a political crisis within the Iroquois Confederacy by persuading many, but not all, Oneida people to side with the patriots. It was a fatal error on the part of the Oneida – their nation is now split into two (one in their ancestral homeland, and the other in Wisconsin from a forced removal). Kirkland went on to found the Hamilton-Oneida Academy (now Hamilton College) – a school for settler American and Indigenous students alike. Although the academy is often painted as a progressive, forward thinking institute, in reality, it was an earlier example of those institutions that wanted to “kill the Indian, and save the man.” Locally, everyone knows the name Herkimer – streets, a town, a county and even a college are named in his honor. But fewer know the names of Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant), Cornplanter, or so many other Iroquois warriors. Or any of the names of those escaped slaves from Upstate New York who joined Butler’s Loyalist Rangers because they saw that their path to emancipation was found by joining the British and putting down the rebellion of slave owners like Washington and Herkimer.

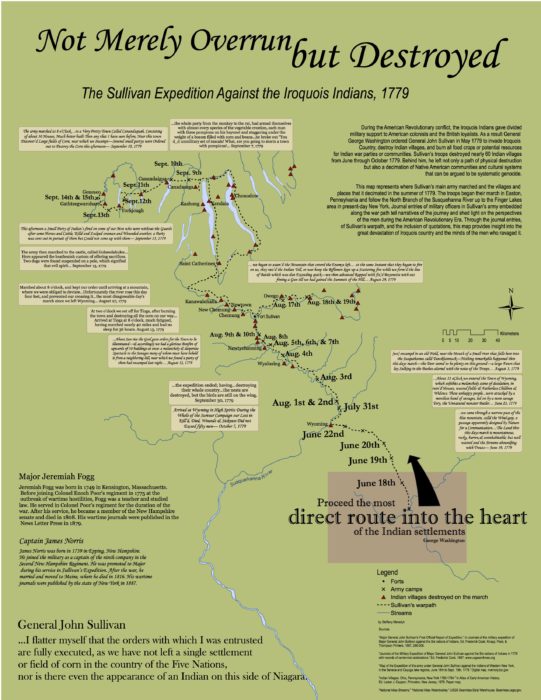

One of the largest omissions of the national creation myth that is conveniently and intentionally left out is Sullivan’s Campaign. This was one of the largest offensive campaigns that George Washington launched during the War of Independence and it occurred just West and South of where I grew up.

In 1779, George Washington gave clear orders to General John Sullivan who was handpicked to lead the campaign against the Iroquois:

The Expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.

I would recommend, that some post in the center of the Indian Country, should be occupied with all expedition, with a sufficient quantity of provisions whence parties should be detached to lay waste all the settlements around, with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed.

But you will not by any means listen to any overture of peace before the total ruinment of their settlements is effected. Our future security will be in their inability to injure us and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire them.

Sullivan carried out Washington’s orders. Thousands of soldiers invaded Iroquois territory with a horrifying display of power and violence. A scorched earth policy entirely burned to the ground over 40 Iroquois villages (it should be noted that these “villages” often had a higher population density than most cities in Europe at the time). Crops were burned, animals killed and people displaced. In one Mohawk village, every single male was arrested and sent to a jail in Albany. The Onondaga, Seneca, Cayuga, Mohawk, Tuscarora and even some Oneida peoples of the Iroquois Confederacy became refugees in their own lands and several thousand fled to Canada to relocate. For Washington and his cause, the offensive was a success. It decisively tipped the balance of power away from the Iroquois and Loyalists. Settlers rapidly took over the lands and villages previously occupied by the Iroquois and the indigenous territory in New York and Pennsylvania was forcefully opened up to the rest of the Great Lakes and even farther west in the longer project of settler colonialism and expansion.

I remember visiting Canandaigua Lake last summer for the first time. As the sun set, my eyes met the glow of a small island. That island was both the birthplace of the Seneca Nation and served as a place of refuge for countless Seneca people in 1777 who fled Sullivan’s troops. My hands shook and my eyes watered over at the sheer depth of what happened there.

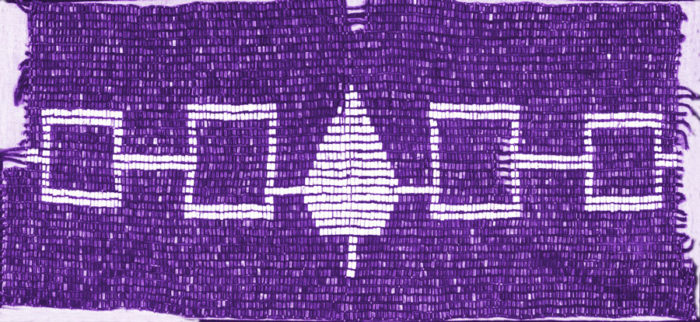

There is a name for this: genocide. It is no surprise then that Washington earned the nickname “village destroyer” and “village devourer.” It’s a name fitting for every president since him. This very same history recently came up with my Mohawk nephews and their tóta (grandmother in Mohawk). We were all sitting down together last year and one of my nephews mentioned that his class was learning about George Washington and, I imagine, the creation myth that surrounded him. Without hesitation, their grandmother responded, “He was a bad man. He was a very bad man.” We talked about their shared Iroquois history, of the genocide of the Iroquois and brutal institution of slaves, but also the resistance waged by Mohawk and slave alike.

There is a great denial that this genocide is an actual genocide. That it even took place. There are no accurate historical markers, no national acknowledgment of what happened, no requirements to teach this in American history classes. And this connects directly to the myth that people keep alive to this very day. And that is, somehow, that Trump and his administration stand as an aberration to what the US has always been, that his grasp of reigns of power is the exception and not the rule to a longer history of process, democratization, to something that is exceptional. That the concentration camps popping up along the US-Mexico border have no historical precedent.

This nation was built on a foundation of genocide and slavery. As people locally celebrate George Washington, the patriot troops at Fort Stanwix and the martyrdom of Herkimer and other militiamen in the Battle of Oriskany, I can only think of the terrified Iroquois refugees who survived an act of genocide, or of the slaves who toiled in the homes and fields of the Mohawk and Hudson Valleys. But I also think about those slaves who fled their conditions of servitude and enlisted with the British Army, including some of Washington’s slaves, or the former slave involved in a plot to assassinate the ultimate slave master and village destroyer. I also think of all of the indigenous warriors who fought to preserve their culture and their way of life during that brutal war.

Historian Gerald Horne is right. He took Zinn’s argument even further and said that the American “revolution” was a counter-revolution. That the war of independence in large part was launched as a response to growing slave rebellions in the Southern colonies and the Caribbean but also to the early signs of a gradual transition to abolition in England and beyond. The writing was on the wall, and something had to be done to secure slavery as an institution. It’s no surprise that 10,000s of slaves fled to and took up arms on the side of the British during the war. To them, that army, with all its contradictions, was one of revolutionary liberation, not Washington’s Continental Army. The ideas of despotism, violence, oppression, slavery and genocide were woven into the very fabric of the foundation of this nation in 1776. So, what do we make of this nation in 2019?

In Trump’s America, the children suffering in concentration camps along the border taken from their parents is not too different from those Iroquois children who were displaced from their homes and their families in 1779 in Washington’s America. It should serve as no irony that just as in 1779, many of the children targeted today by the “village destroyer” are also indigenous – from Mexico and Central America. And just as in 1779, so many targeted by the village destroyer are Black, are poor, are destitute.

I hope that a major takeaway my Mohawk nephews had about our discussion on Washington was not just about the violence and suffering he inflicted on the Iroquois and on slaves, but that countless Iroquois and slaves resisted against that oppression. This is not a question of history. That resistance continues. Today, a small group of activists from across the lands where this genocide took place are descending on the ICE Detention Center in Batavia, NY – a prison for immigrants built by a nation that’s been in the business of creating refugees and displacing people since 1776. Even in Philadelphia, a large group of Jewish activists and their supporters proclaiming “Never Again is Now” marched on the ICE facility and are disrupting the July 4th parade with a demand to shut down the concentration camps.

Village destroyers, from Washington to Trump, have always known which side they’re on – the side of slave owners and land speculators, prison wardens and generals, white supremacists and killers, politicians and capitalists – we need to have a better idea of what the creation myth of this nation is to better understand that the US today is just a visceral embrace of what it always was. We should call that creation myth for what it is: a myth. Just as the Iroquois warriors and Black freedom fighters who fought against the village destroyer Washington and the system of oppression he represented, we need to follow in their footsteps, and join the growing movement to shut down these concentration camps, and create a world where there are no more village destroyers.

Brendan Maslauskas Dunn is a member of the Black Rose Anarchist Federation who lives in Mohawk and Mahican Territory in Upstate NY.