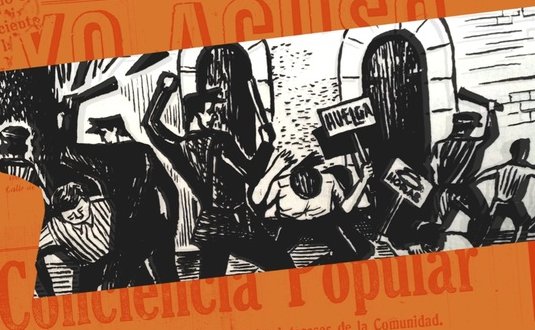

Puerto Rico continues to remain a colonial territory of the United States since it’s military invasion and occupation in 1898 but the rich history of working class and left movements on the island are often little known within the US left. We are excited to publish this essay, which appears courtesy of Theory In Action journal, on Puerto Rican anarchism in conjunction with an interview with Jorell on From Below Podcast episode “Anarchism and Socialism in Puerto Rico.”

By Jorell Meléndez-Badillo

This essay intends to shed some light on the discourses elaborated by the anarchists in Puerto Rico at the turn of the twentieth century. The period was characterized by an accelerated change in the means of production, caused by the US invasion and that set forth a complex situation for the ascendant working class. It is in this context that local anarchists developed native ideological postures from outside official intellectual circles. We will analyze their intellectual production in order to determine how these individuals tried to shape their own identity while creating transnational bonds with anarchists from the Caribbean, America, and Europe.

Over the past several years a debate has erupted inside international libertarian intellectual circles concerning the origins of anarchism. Many recent thinkers, such as George Woodcock and Peter Marshall, would agree with their predecessor Max Nettlau that the “history of the anarchist idea is inseparable from progressive developments and the aspiration towards liberty” (Nettlau 1977: 13). This view traces Anarchism’s origin to thinkers such as Lao-Tse [607 b.c.], Zenón [342- 270 b.c.] and Carpócrates [II century], (Marshall 2008: 53; Cuevas Noa 2003: 43). On the other hand we find the position of Michael Schmidt and Lucien van der Walt, whose book Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism proposes Anarchism’s origins in the context of the modern working class and the radical socialist movement of the First International in the 1860s (Schmidt & van der Walt 2009: 34).

Anarchism was not immutable. It expanded throughout the globe in a cosmopolitan manner, while maintaining a core ideological framework. It is through this migratory process that anarchism will contain particularities according to the geographical space in which it develops. If we accept the thesis of the unequal development of nations, we must then affirm that anarchism cannot be analyzed as a mere concrete material product that travels from one place to the other but as an ideology subordinated to the space in which it is created.

The situation of the Puerto Rican working class throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century could be considered one of vast complexity. Even though there was a display of class-consciousness, materialized through various organizations based on solidarity and mutual aid during the last three decades of the nineteenth century, it was not until 1899 that the first labor syndicate was organized in Puerto Rico. The material conditions were changing rapidly with the proletarization of the majority of the Puerto Rican workers because of a change in the modes of production, caused by the entrance of U.S. capitalism in the local economy since 1898. It is because of this situation that the most progressive sectors inside the working class elaborated discourses based on their analysis of various foreign ideologies. They wanted to comprehend their historical reality and guide it through responses or alternatives to the official discourse of the State and the organizations that were supposed to look out for their interests. It is in this context that anarchist ideas start to propagate throughout the island.

Since we cannot talk about labor organizations managed by individuals adhering to the anarchist ideology, as in the cases, for example, of Spain’s C.N.T. or Argentina’s F.O.R.A, we argue that anarchism was not a homogeneous ideal inside the Puerto Rican working class as would be the cases in different historical contexts—not only in the places mentioned, but on a global level. On the other hand, the leadership of the Free Workers’ Federation (F.L.T. for its acronym in Spanish), which was the only syndicate during the period studied, gravitated towards the reformist ideas of trade unionism put forward by the American Federation of Labor. Nevertheless, we need to point out the fact that there were workers inside the ranks of the F.L.T., who could be considered part of the second sphere of the organization, who sympathized with libertarian ideas, such as José Ferrer y Ferrer, Luisa Capetillo, and Ramón Romero Rosa. We also need to mention the individuals of the base of the organization, who belonged to a great variety of occupations such as shoemakers, typographers, and cigar makers. The latter is where anarchism penetrated deeply as rank-and-file workers put anarchist ideas into practice in factories and other workplaces.

Puerto Rican anarchists relied on a vast quantity of literary propaganda. Several of the foreign books were sold at the local union buildings, in meetings, and through mail. This literature was spread through at least two distributing houses such as Germinal and La Reforma Social which provided service for the whole island. The circulation of these books and pamphlets presupposes a transnational contact with anarchists from different parts of the Caribbean, Latin America, and Europe and lets us appreciate the materialization of the internationalist idea advocated by anarchism. Not only did they send books but they also shared writings, letters, and ideas. In one occasion, the periodical Voz Humana was suffering from economic hardships caused by striking tobacco workers in Caguas. In response, international publications such as ¡Tierra! in Cuba provided Voz Humana with economic aid. This action not only demonstrates solidarity between anarchists on an international level but it demonstrates the great esteem and respect the foreign anarchists felt towards their Puerto Rican comrades.

Nonetheless, it would be an error to affirm that anarchism was a product imported from abroad as if it was mere physical merchandise. Instead, we could argue that the individuals adhering to anarchism in Puerto Rico elaborated a native discourse. Even though it is true that their ideas were developed through the lecture and analysis of foreign anarchist intellectuals—most of them Europeans translated to Spanish through Spain, which were then exported to the Caribbean—their immediate historical conditions forced them to transform these ideas according to their daily practices. This led them to elaborate their own narratives on contemporary topics such as marriage, war, exploitation, and free love, from an anarchist perspective.

Puerto Rican anarchists were hopeful about the future and believed in the anarchist ideal as a mechanism to change it in their favor. In relation to this Juan José López called on the exploited to “go on and tell our brothers to hold on tight to the redemptory lines of Anarchy, which brings us a clear path, new days, more space, more light, more teachings, more realities, more hope, with a life of love and harmony, a life of lullabies and melodies, life of collective sciences, without the monopolies of instructive schools, with free rational and humane learning, without mystical ideas, without vane ideas…” (López 1910: 10). And even though they demonstrated hope in the process they maintained the idea that it shouldn’t be considered utopian because, as Luisa Capetillo argued, “everything that is assured for the future, no matter its nature, is utopian” (Capetillo 1992: 73).

Nonetheless, they recognized, as established by Venancio Cruz, that the actual situation was created by “the fatal bourgeois philosophy that was conceived in unbalanced minds” and instituted “politics as a vengeful and severe tribunal, trading the most sacred liberties and oppressing the people under its fierce iron hand” (Cruz 1904: 10-11). This led them to consider, as expressed by Fra Filipo in the newspaper Voz Humana, “no, it’s not in the heart of the political parties where we should look for our regeneration, emancipation, and development in all orders of life. We need to go to the heart of the workers’ organizations.” (Filipo 1906: 3). This is of crucial importance when we consider the fact that the F.L.T. organized a political party in 1900 in order to take their battle into the political spectrum. The radical workers had a double discourse in relation to this argument. Some advocated non-cooperation while others argued they needed a variety of tactics, including a workers’ party. The anarchists also thought “the proletarian is actually in the condition to fight for his liberty, if he makes the most of the opportunity in…class struggle…By giving up the slave-like conditions it is his duty to fight relentlessly, opposing the actual institutions with heroic resistance through his SYNDICALIST and REVOLUTIONARY unions. (Dieppa 1915: 11-12).

Despite their strong rhetoric, they weren’t able to elaborate a coherent discourse around how to create that process in Puerto Rico. We should point out that Ángel María Dieppa’s words cited above were published in 1915, the year in which the Partido Socialista (P.S.) was established. The P.S., unlike its predecessor—the 1900s Partido Obrero Socialista— tried to hegemonize socialist thought not only inside the syndicate but also across the political spectrum. This was a huge blow for the anarchists because they did not enjoy the sympathy of the leaders of F.L.T. nor of the Socialist Party. In fact they were constantly under physical and verbal attack from both the State and the reformists inside the labor movement.

We also need to point out that, in contrast to what has been presented in the official Puerto Rican historiography, the anarchists at the turn of the century were conscious of their immediate historical reality; launched harsh criticisms against the democracy that was promoted by the politicians, the bourgeoisie, and the State; and distrusted the changes imposed by the new metropolis that was established after the North American invasion of Puerto Rico in 1898. With regard to republics, they argued that “it doesn’t matter all the effort they put into trying to appear democratic and liberal…it is the same as the monarchy and the empire, it is authority, goddamn authority which in some places is called republic, in others empire and in others monarchy. It is a crime in disguise” (López 191[?]: 19). And it is through examples of the repressive mechanism used against the workers and anarchists of the United States that Juan José López elaborated his criticism. He mentions cases such as the Chicago Martyrs, the killing of women in Colorado, the assassination of tobacco workers in Tampa, and the unceasing harassment of the Industrial Workers of the World and the Magón brothers (López, 191[?], 22). They also criticized local workers who adopted a false discourse of liberty under the flag of the United States, which lets us appreciate their consciousness in relation to the colonial status of the island. Along the same lines, while in March 1916 various anarchists such as Jean Grave, Carlos Malato, Elisée Reclus and Piotr Kropotkin signed a manifesto backing the allies during the First World War, in Puerto Rico Juan José López in Puerto Rico attacked this posture severely through his writings (López, 191[?]).

Puerto Rican anarchists saw religion as one of the worst evils tormenting the workers and as the root of social discord. This is of the utmost importance when we consider the fact that Puerto Rico had a deeply Catholic government that was established by the Spanish monarchy in 1508 and lasted up until the invasion of the United States (which did not abolish it but instead opened up the island as fresh new ground for other Protestant religions). These conditions made a huge impact on how the average Puerto Rican constructed his social imaginary and interpreted his immediate reality. Even though the radicals elaborated a very forceful anticlerical discourse, it was not shared by all of the local anarchists. For example, in 1901, José Ferrer y Ferrer, under the pseudonym of Rabachol, wrote an article in the newspaper La Miseria which exalted the figure of Satan who “enjoyed a free and emancipated life” when he rebelled against God (an echo of Bakuninist rhetoric). Luisa Capetillo, in contrast, created a discourse that defended Spiritualism, while Juan José López, writing from a materialist perspective, lashed out against any type of idea coming from a spiritual standpoint.

The anarchists also formulated critical positions in relation to prostitution, arguing that this practice, according to Braulio López, “is not an instinct nor an inheritance. It is produced by the force of circumstances: it is the daughter of social conditions” (Braulio López 1901: 1). This led them to see prostitutes, not as women filled with lust, but as exploited workers whose conditions compelled them to sell their bodies, making them comrades in the struggle. Marriage, on the other hand, constituted legalized prostitution. Venancio Cruz expressed himself on the topic by arguing: “it was historical justice, in order to set his predominance and to exercise more influence in the popular masses that led man to invent marriage” which “condemned two beings to a living lock-up, wanting to reduce their lives to a simple room, taking them away from the current of solidarity, blinding their eyes to reason so they could not enjoy themselves in the greatness of life, subjugating them like two slaves so they cannot rebel…” (Cruz 1904: 48).

As we have seen, Puerto Rican anarchists created various discourses in order to comprehend their immediate reality. Even though much of these ideas responded to mere interpretations of international currents and debates, others, as mentioned above, were native discourses dictated by their historical conditions. We need to remember that even though the working class was going through a complicated process of proletarization which altered their relations towards the modes of production, they also were trying to understand the changes in their social relations caused by the invasion of the United States, massive migrations outside of the island, natural catastrophes, and other complexities of the life in early twentieth-century Puerto Rico. It is for this reason that we affirm, without hesitation, that we cannot talk about a common homogeneous anarchist ideal even in a limited geographical context such as the Caribbean.

Jorell Meléndez-Badillo is a historian and assistant professor at Dartmouth College focusing on the global circulation of radical ideas from the standpoint of working-class intellectual communities in the Caribbean and Latin America.

This article was first published in Theory in Action, Vol 5, No 4, October 2012, a journal of the Transformative Studies Institute. Reprinted by permission.

References

Periodicals:

- Filipo, Fra. “Nuestro deber”, Voz Humana, September 30, 1906.

- López, Braulio. “La prostitución”, La Miseria, March 20, 1901.

Books:

- Cruz, Venancio. Hacia el porvenir. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Tipografía La República Española, 1904.

- Cuevas Noa, Jose, Francisco José. Anarquismo y educación: La propuesta sociopolítica de la pedagogía libertaria. Madrid, Spain: Fundación de Estudios Libertarios Anselmo Lorenzo, 2003.

- Dieppa, Ángel María. El porvenir de la sociedad humana. Puerta de Tierra, Puerto Rico: Tipografía El Eco, 1915.

- López, Juan José. Voces libertarias. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Tipografía La Bomba.

- Marshall, Peter. Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. Oakland: PM Press, 2008.

- Nettlau, Max. La anarquía a través de los tiempos. Barcelona, Spain: Ediciones Jucar,

- Ramos, Julio. Amor y anarquía: Los escritos de Luisa Capetillo. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Ediciones Huracán, 1992.

- Schmidt, Michael and Lucien Van der Walt. Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism. Oakland, AK Press, 2009.