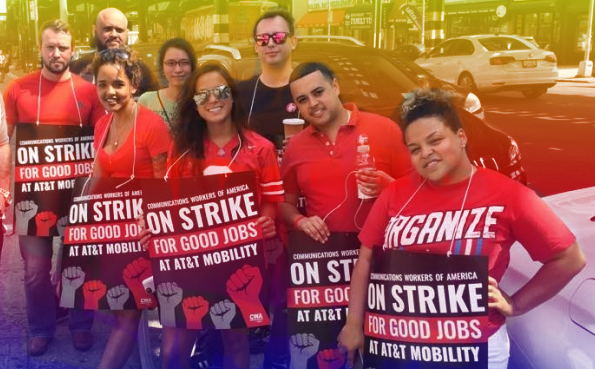

This past month thousands of AT&T workers across the country have gone out on short, locally-organized Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) strikes in protest of company intimidation during contract bargaining and other issues. Two separate contracts for the workers organized under the Communications Workers of America (CWA) at AT&T expired on April 15 but negotiations continued and news reports state that the company went around the union and its bargaining team to email employees that they had reached a “fair” and “final” offer.

For this interview we will be speaking with Patrick who is a CWA member and union steward at his job site in the Twin Cities area where several hundred workers went out on two separate ULP strikes. He will be detailing some of the long term organizing at his work site and the dynamics that led into the strike. Patrick is also a long time member of the mainly Midwest based First of May Anarchist Alliance (M1) and for the purposes of this interview his name has been changed and certain details left out in order to protect their identity.

BRRN: We’re excited to see more workers joining the upsurge in strikes across the US so far this year, which are critical to rebuilding a militant labor movement. First, tell us about the issues leading up to the strike and for those who may not be familiar, what is an “unfair labor practice” strike and why has the union used it?

Patrick: Thanks for reaching out. Black Rose/Rosa Negra is an important organization and I’m glad to talk with you. The immediate spark for these strikes is the expiration of two of the sizable contracts – called the Legacy T and Midwest contracts that AT&T has with the CWA – and the sharp concessions that AT&T continues to demand form it’s workers. Alongside this are specific local grievances that have been sore points between workers and the company for some time. At my workplace, we have been waging a years long battle over how the company interprets and discriminates in its implementation of state and municipal sick pay laws.

By going on limited Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) strikes union locals can confront specific issues when, because of the expired contract, they are unable to use a negotiated grievance procedure. The ULP strike also allows union locals to test the strength of their organization and the morale of the membership – but without risking too much. ULP strikes maintain the legality that wildcat strikes challenge but without the danger (or the force) of an unlimited “economic strike” over the issues of the contract as a whole [for legal definitions, see here].

There are also a couple important things that make up the context for this little wave of ULP strikes against AT&T. The first and most important is the change in mood and attitude of large groups of working people in the US. Some of the conservatism and fear has started to fall away and a “fuck it, let’s go for it” type of attitude has become more widespread. I don’t want to oversell this – it’s nowhere near a majority and it’s not a revolutionary outlook by any means – but it’s a change and it’s real. Where it comes from makes for an interesting discussion. I can’t help but think that the recent waves of mass struggles like the 2011 Wisconsin Uprising, Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, the #MeToo phenomenon, and the advances of the LGBTQ community that have had an impact on the class as a whole – many workers sympathized and participated in these struggles, or wish they had. The more recent teacher strikes were important too – they showed us again that the strike can be an effective weapon and that regular people in regular places can use it even when they are being told by the authorities that they can’t.

Related to all this is the apparent disorder of the establishment. From the total gridlock under Obama, to the bizarre and dangerous Trump show – I think many people are starting to think we can’t look at the government and the corrupt political class to solve our problems or to stick up for us – there’s an openness to ideas that would have recently seemed extreme or out of bounds.

BRRN: There’s been some descriptions of the strike as a “wildcat strike” but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Can you tell us more on that?

Patrick: “Wildcats” are unofficial strikes organized outside of or against the union leadership – or as often is the case, secretly organized by the union, but for legal or other reasons portrayed as an unofficial action. The AT&T ULP strikes have not been wildcats. Instead they are officially organized on a local level and while not coordinated by the CWA [national union leadership], workers and local officers are certainly aware of and inspired by the other strikes. But what this means is that more than a dozen Locals have had to learn how to motivate and carry-out action shutting down work – and thousands of workers now have that experience.

For many years the big mainstream unions appeared to have given up on strike action but the CWA seems to have lost its allergy to going out. CWA workers at Verizon have gone on strike in 2011 and 2016 and the fairly recently organized AT&T Wireless workers struck for the first time in 2017. I’m told that Joe Burns’s important book Reviving the Strike got passed around CWA leadership.

My view is that this change in the union bureaucracy is not from a new found determination to wage class struggle but a realization that there was little place at the establishment table for the unions anymore – along with a growing pressure from the ranks described above. The bureaucracy still sees strikes and direct action as auxiliary tactics to elections and lobbying politicians though, and crass collaboration with the bosses is still all too normal. For instance while AT&T was refusing to seriously negotiate with the Wireless workers last year, the CWA publicly endorsed AT&T’s controversial purchase of Time-Warner to help smooth government approval.

BRRN: Can you tell us more about the workforce at your site, demographics and how has the strike played out so far with morale and participation?

Patrick: I work in a call-center that processes payments for AT&T’s business and corporate customers. It’s a “cube-farm” – three floors of cubicles (currently covered in union posters and signs) where workers answer phones and emails all day. Pretty miserable work, really.

The 400 or so workers in our building are the job’s saving grace. There is a wide range of ages from early 20s to late 60’s, slightly more women than men, and about 40% people of color. It’s one of the more “gay-friendly” corporate workplaces I’ve ever seen, so most queer folks working here are openly “out” on the job and two workers have transitioned genders while I’ve been here.

Politically, most workers identify more-or-less with the Democrats with a strong-contingent of Bernie Sanders supporters. There’s also a number of vocal conservatives – some of whom regularly participate in the union [and even] went out on strike. We had a crew of Wobbly dual-carders at one time, about 10 people who were part of the IWW, that helped lay the basis for some of the organizing and action that’s been accomplished here.

Three years ago, when the last contract expired we went out on a one-day grievance strike with about 70% of the workers participating. I wasn’t sure if we’d hit those numbers again – my sense was that our hardcore group of union activists was larger and more militant, but that the looser base was maybe less committed than before. But the strikes this time were actually bigger, including both newer employees and some workers that stayed in last time. The group that organized the two strikes this year was broader, more organized and more confident.

Going out on strike is a blast, a big “fuck off” to your manager. There’s a feeling of empowerment and solidarity, a feeling and that we are doing something brave and special. People were taking selfies and posting videos from the picket-line. But, there’s also still some fear. The contract isn’t settled. The strikes, while impressive, haven’t yet beaten the corporation and settled our issues.

BRRN: You’ve been active within your union for a number of years as a steward, can you tell us about some of these past efforts, successes and failures?

Patrick: Soon after I started working here I hooked up with some younger workers who had faced roadblocks from suspicious local officers. This was around the time of George W. Bush’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq – and the younger workers were somewhat politicized by that so I tried to be helpful with this group as it cohered into a pole of opposition within the local.

Around this same time the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) re-launched in the Twin Cities. The local Wobbly campaigns at Starbucks and Jimmy Johns, and militant solidarity with strikes at the University of Michigan and Northwest Airlines made the IWW branch very dynamic and in this context a number of co-workers at AT&T were recruited into the IWW.

There were some real limits to our organizing. [For instance] we were never able to really figure out how to make the IWW work at AT&T. Initially the group at work had oriented toward running in union elections against the local leadership – I was ambivalent, but went along and tried to push stuff politically in a sharper direction. We ran a slate and lost but got a respectable 40% of the vote. The local union leadership had opposed us with fear-mongering and lies – a rumor was put out that we wanted to get ahold of the union treasury for “drug parties!”

With the turn toward the Wobblies, the politics of the group became more radical, but a lot of the focus moved to supporting IWW campaigns and other struggles outside of work. Some people basically took an abstentionist line towards activity in our CWA Local. Another problem was the composition of our group – while the workplace was quite diverse, our group was overwhelmingly young, white, and without kids.

Some of these contradictions came to a head in 2011 when we met to decide how to approach the next round of local union elections. This was six years and two election cycles since we had last run, and there was feeling that with our longer time on the job and now proven track records we could possibly win some spots on the local Executive Board. I argued that instead we should discuss a program, a set of goals that we could run on and be held accountable to – then whoever the individual candidates would be less important and less focused around egos – but my arguments didn’t win out and instead an agreement was made that we would support each other but put out our own literature. I ran for Chief Steward on an explicit “Solidarity Unionist,” IWW-influenced program.

Despite our agreement to support each other, the other candidates from our group panicked when I put out my first campaign literature. They were certain that it was too radical, would make me unelectable and hurt their chances of winning. The three other candidates formed a bloc with part of the old-guard on the Executive Board and ran a slate on the weakest basis of “change.” Their slate opposed the Local President but also included the incumbent Chief Steward running against me.

During the campaign I had laid out what should be done with the Chief Steward position: end secret deals with Corporate HR over discipline, build a militant stewards force in the workplace, open the local union to further democratic participation and accountability, oppose concessionary contracts, and support struggles outside the workplace. These politics won out but I was now joining an entirely hostile Executive Board.

Over the next six months the E-Board voted three separate times to either strip me of my duties or to outright remove me as Chief Steward but we were able to overturn their decisions by organizing and mobilizing for the next monthly membership meeting. After being humiliated by the membership reversing their decisions the local President and then the Vice-President each resigned and when the dust settled – and another one of our group was elected as Executive Vice-President – I finally had the room to implement at least the basics.

The steward force was expanded from five all white, and majority men to 15 who were majority women, people of color and Black. We began holding monthly steward meetings in the workplace to discuss issues on the job and plan actions like workplace marches on abusive managers, or how to mobilize around particular grievances. The monthly steward meetings also had discussions on broader political issues and I distributed radical readings. We even read as a group Marty Glaberman’s classic poem critiquing the role of shop stewards “It’s Out of My Hands.”

We also revitalized committees within the union and made them effective fronts of activity. The Health & Safety Committee surveyed the membership and forced the company to address air quality concerns. After a co-worker died of a heart attack at home, we read an article about EKG machines and demanded the company provide them on each floor at work. When the company claimed they didn’t have the budget for it we just started fund-raising ourselves for EKG machines that the Health & Safety Committee would control – which embarrassed the company so much they magically found the money and installed three machines.

The Workers’ Rights Committee has been fighting long-standing situation of unfair and discriminatory implementation of state and municipal sick-time laws – which is ironic since this has become one the labor movement’s main ways to effect reforms. These issues provided the reason for our walk out in 2015 and the first of the two strikes in the last month.

BRRN: You’ve also been a long time participant in various anarchist and related organizing efforts going back to the 1980’s and a member First of May Anarchist Alliance (M1), an anarchist political organization founded in 2011. Tell us about how this has informed your strategy and approach to workplace organizing and how this has played out?

Patrick: All of my activity in the workplace and the union comes from my anarchist politics, and I’d say from the specific approaches promoted by M1 which is a small organization based in the Twin Cities, Detroit and Chicago and a few individuals elsewhere. Despite our modest size we have had some impact, especially in what we describe as “working-class defense organizations” – like the IWW, the General Defense Committee, Solidarity & Defense, the Detroit Eviction Defense, and my local CWA union.

M1 in particular encourages an orientation to the working-class – that it is the millions of workers that have the capacity and interest to make a revolution. We seek to relate to the class ias equals, and not as “leaders,” in the hierarchical sense. We have always been critical of the approach – popular in some left and even anarchist quarters of taking jobs as staffers of unions and community groups as a way of organizing with the class. That approach makes militants accountable to the union bureaucracy instead of grassroots workers and cultivates an elitist self-conception.

We strive to be able to discuss and debate and build around a full revolutionary vision and not just bread and butter issues. We reject the idea that workers only care about narrow economic concerns [and] aim to build “personal-political” bonds with our co-workers over time – and try to not only to “tell” people about our ideas, but to show them in practice. And we do this as equals not as specialists or “leaders.”

We don’t have all the answers so we value tactical experimentation within our overall strategy and values. So for instance, some comrades who organized at UPS, built their organizing much more outside of the union representing the shop than the experience I describe above.

For further reading on First of May Anarchist Alliance we recommend “Our Anarchism” and “Social Struggle in the Coming Period.” For more reading on militant labor organizing “Unionism From Below: Interview with Burgerville Workers Union” and “Strike to Win: How the West Virginia Teacher’s Strike Was Won.”